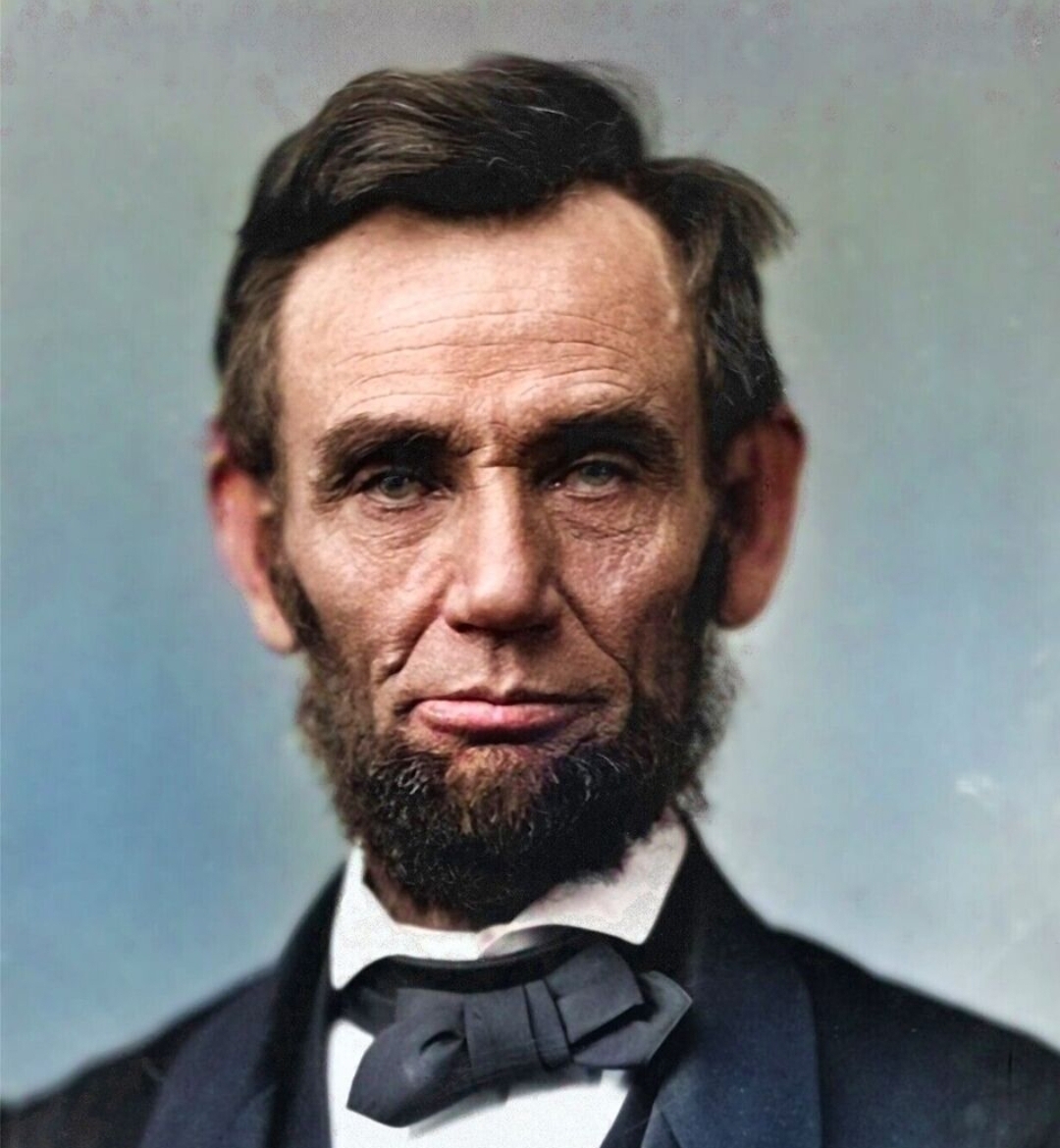

There is a strong argument that Abraham Lincoln was an opportunist who used the Problem-Reaction-Solution model to reshape the American government. While his presidency is often framed as a moral crusade against slavery, his actions suggest a deeper political strategy aimed at centralizing federal power and shifting the U.S. from a decentralized confederation of sovereign states into a national government with ultimate authority over the states.

Problem: Secession and Slavery as a Crisis

Before the Civil War, the United States was a federal republic where states maintained significant autonomy under the Constitution’s Tenth Amendment. Many Southern states, believing in the compact theory of government, argued that since they voluntarily joined the Union, they could also voluntarily leave it. Lincoln, however, rejected the idea of secession entirely—not just to preserve the Union, but also to establish a precedent that the federal government held ultimate power over the states.

Slavery was the public justification for war, but Lincoln himself admitted that his primary goal was preserving the Union—not abolishing slavery. In an 1862 letter to Horace Greeley, he stated:

“If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.”

This suggests that while Lincoln may have personally opposed slavery, he was first and foremost focused on maintaining federal control over the seceding states.

Reaction: The Civil War and National Emergency

Once the South seceded, the war created the necessary **”reaction”—a national crisis—**that allowed Lincoln to justify an expansion of federal power. He used executive authority to:

- Suspend habeas corpus (jailing dissenters without trial, including state legislators and newspaper editors).

- Raise an army without Congressional approval, which was unconstitutional under Article I, Section 8.

- Institute a national draft, an unprecedented federal action.

- Order the arrest of state officials who opposed the war effort, further eroding state sovereignty.

Each of these actions violated the constitutional balance of power, but Lincoln defended them by arguing that preserving the Union was more important than strict adherence to the Constitution.

Solution: Nationalizing the Government and Ending State Sovereignty

The result of the war was not just the abolition of slavery, but the fundamental transformation of the U.S. government from a federalist system (where states had real power) into a national system (where the federal government ruled over the states as administrative districts).

- The 14th Amendment (1868) redefined citizenship, stating that all Americans were now citizens of the United States first, rather than of their respective states. This undermined state sovereignty and made federal law supreme over state law.

- Reconstruction Acts placed Southern states under military rule, enforcing federal policies at gunpoint.

- The Civil War “justified” permanent federal authority over the states, effectively nullifying the compact theory of government. The idea that states could nullify federal laws or secede was now a settled issue—under the federal government’s authority, not the states’.

Lincoln’s Real Legacy: The Birth of the Modern National State

Before Lincoln, the United States was a collection of states bound by mutual agreement—after Lincoln, the federal government became the undisputed central authority over those states. He may not have been the first president to expand federal power, but he was the most effective at setting the precedent that the Constitution could be bent or ignored in times of crisis.

It is likely that Lincoln understood that slavery would eventually end due to economic and technological factors (as discussed previously), but he used the issue as a moral and political justification to achieve a much greater goal—the expansion of national government power. The war not only ended slavery but also ended true state sovereignty, turning states into administrative districts of an all-powerful federal government.

In this sense, Lincoln masterfully used the Problem-Reaction-Solution strategy to transform the United States. Whether one sees this as necessary for national unity or a betrayal of the Founders’ vision depends on perspective. What is undeniable is that Lincoln set the precedent for future government expansion in times of crisis, a trend that has continued to this day.

There is a strong historical argument that slavery in America would have gradually ended due to technological advancements and economic shifts, even without the Civil War. While moral and political debates were central to the abolition movement, economic and technological factors played a crucial role in making slavery increasingly inefficient and unsustainable.

The Decline of Agricultural Slavery

By the mid-19th century, the Industrial Revolution was transforming economies worldwide. Mechanization and new farming equipment—such as the mechanical reaper, the steam engine, and later, the tractor—were increasing productivity, reducing the need for manual labor. While the cotton gin (invented by Eli Whitney in 1793) temporarily made cotton farming more profitable and extended the lifespan of slavery in the South, the long-term trend was moving toward automation and wage labor.

In other parts of the Western world, slavery was already being phased out due to economic realities. In Britain and much of Europe, slavery was abolished without civil wars—often because industrial economies found wage labor more flexible, cost-effective, and sustainable. Factory production was becoming the dominant economic force, and industrialists needed a workforce that was mobile and could participate in consumer markets, something that slavery could not provide.

The Cost of Maintaining Slavery

As industrialization spread, slavery was becoming more expensive to maintain. Plantation owners had to provide food, housing, and medical care for enslaved workers, regardless of their productivity. In contrast, wage laborers could be hired and fired as needed, making them a more efficient and cost-effective workforce. Additionally, slavery limited innovation and diversification—Southern economies remained dependent on cash crops like cotton, tobacco, and sugar, while the North embraced industry and technological progress.

Had slavery continued, Southern states would have eventually struggled to compete with more modern, mechanized agricultural methods. Landowners would have been incentivized to replace human labor with machines, much like what happened in the North and in other industrialized nations. Over time, enslaved labor would have become more of a burden than a benefit, leading to a gradual transition toward wage labor, sharecropping, or other forms of employment.

Changing Global Attitudes and Pressure

By the mid-19th century, global pressure against slavery was mounting. The British Empire had abolished slavery in 1833, and France followed in 1848. Many European nations and trading partners saw slavery as an outdated and immoral system, making it diplomatically and economically disadvantageous for the U.S. to continue it. If America had not fought a civil war over the issue, it’s likely that international trade pressures, economic competition, and diplomatic relations would have pushed the country toward abolition in the coming decades.

Would Slavery Have Faded Away?

While the Civil War accelerated the end of slavery, it is highly plausible that slavery would have gradually collapsed due to economic and technological forces. The South would have been forced to modernize, just as the North had done, making the institution of slavery more of a hindrance than an asset. Eventually, a shift to wage labor and mechanization would have occurred—likely through legal reforms, economic shifts, or increasing political pressure.

However, it is worth noting that even if slavery had faded without war, deep racial inequalities and exploitation would likely have persisted. The transition from slavery to sharecropping, segregation, and Jim Crow laws suggests that while forced labor may have ended, systemic oppression could have continued in different forms. Nevertheless, history shows that technological progress and economic incentives often drive social change, and slavery was ultimately incompatible with a rapidly modernizing world.

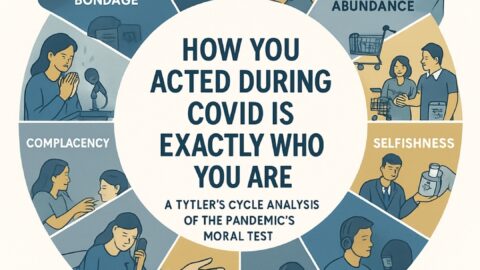

The Evolution of Slavery: From Chains to Contracts

Physical slavery, as it was practiced in the past, became economically and technologically obsolete with the advent of the Industrial Revolution. The rapid modernization of society, especially in the 19th and 20th centuries, made traditional forced labor inefficient compared to mechanization and industrial-scale production. However, the fundamental principle of control over human labor did not disappear—it simply evolved into new, more sophisticated forms of economic and psychological bondage.

The Transition: From Physical to Economic Slavery

The Decline of Traditional Slavery

- Slavery had long been an economic system based on forced human labor, but with the rise of machines, steam power, and later electricity, human muscle was no longer the most efficient means of production.

- Industrialists realized that an economically dependent worker was more profitable than a physically enslaved one. Unlike slaves, workers had to pay for their own food, housing, and healthcare, shifting the cost burden off their “masters” while still keeping them dependent on employment.

- Debt-based economies replaced direct ownership of people—instead of a master providing for basic needs, the worker was now responsible for acquiring these essentials through perpetual labor.

The Birth of Debt Slavery

- The creation of central banking and fiat currency systems (such as the Federal Reserve in 1913) laid the foundation for a new form of feudalism—one where debt replaced chains.

- Governments, corporations, and banks manufactured economic dependence through credit systems, mortgages, student loans, and inflationary currency policies.

- Unlike traditional slavery, where ownership was absolute, modern debt slavery traps individuals in an endless cycle of labor to pay off never-ending financial obligations (mortgages, car loans, medical debt, and taxes).

- Wage slavery ensures that people work just enough to survive but never enough to gain true financial independence.

Neofeudalism: The Modern Plantation System

Corporations as the New Lords

- In medieval feudalism, peasants worked the land and gave a portion of their productivity to the lords. Today, corporations and banks serve as the new aristocracy, extracting wealth through rent-seeking, high-interest loans, and inflation.

- Corporate monopolies ensure that necessities like healthcare, housing, and education remain artificially expensive, keeping people in a constant state of financial struggle.

The Illusion of Choice

- Feudal serfs were bound to the land, just as modern workers are bound to a system of wages, taxes, and debt that offers little true mobility.

- The illusion of freedom is maintained through consumerism, entertainment, and digital distractions, keeping people from realizing the depth of their economic servitude.

State as the Enforcer

- Just as kings and lords controlled serfs, governments enforce economic dependency through taxation, regulation, and monetary policy.

- Social policies like welfare and universal basic income (UBI) create the illusion of relief while ultimately reinforcing dependence on state control.

Breaking the Cycle

- The first step in escaping modern economic slavery is recognizing its existence. The chains are now psychological and financial, not physical, but they are just as restrictive.

- Decentralized finance (crypto), self-sufficiency (homesteading), and reducing reliance on corporate employment offer pathways to freedom, but they require a fundamental shift in mindset.

- Just as physical slavery required abolition, modern economic slavery demands an awakening—a realization that the system is designed to perpetuate dependence rather than true prosperity.

In short, physical slavery was replaced by debt, wage dependence, and corporate feudalism, making the chains of servitude less visible but more effective than ever.

A New Master: From Chattel Slavery to Global Enslavement

The abolition of slavery in the United States, marked by the 13th Amendment, was celebrated as a great moral victory. However, while physical chains were broken for African Americans, the world was quietly being ushered into a new, more insidious form of control—one that did not discriminate by race but instead sought to enslave all people through economic dependency, bureaucracy, and financial manipulation. The plantation was no longer confined to the American South; it became global, disguised under the name of progress and modernity.

Slavery Rebranded: The Rise of Economic Enslavement

From Forced Labor to Wage Slavery

- Before emancipation, slaves were property, and their masters were responsible for housing, feeding, and maintaining them. Once freed, they were suddenly responsible for their own survival, but without land, resources, or capital, many ended up in sharecropping, which was slavery by another name.

- This was not limited to former slaves—as industrialization expanded, even poor whites and immigrants were drawn into factories and company towns, where they labored under conditions not much different from slavery, often earning just enough to stay alive.

The Banking Cartel: Debt as a New Form of Chains

- The rise of central banks and fiat currency systems (like the Federal Reserve in 1913) shifted the power structure. Instead of being directly owned, people became indebted to financial institutions that controlled access to money, homes, and education.

- Unlike physical slavery, where resistance was possible through rebellion or escape, debt slavery is nearly inescapable—governments and corporations manipulate inflation, wages, and taxation to ensure perpetual economic dependence.

A World Enslaved: Globalism and Corporate Feudalism

The Shift from Sovereignty to Global Control

- After the Civil War, the United States moved away from a decentralized government based on state sovereignty and toward a powerful national government. This mirrored what was happening globally, as international financial elites sought to centralize economic and political power.

- Institutions like the United Nations, International Monetary Fund (IMF), and World Bank became the new masters, dictating policy to nations through debt-based agreements.

Corporations as the New Slaveowners

- Slavery was once controlled by plantation owners; today, multinational corporations own the global labor force.

- The outsourcing of jobs to low-wage nations ensures that workers remain in a state of subsistence living, barely able to survive while producing wealth for the elite.

Surveillance and Digital Control

- Unlike the old slave system, which relied on physical enforcement, modern control systems use technology, surveillance, and psychological manipulation.

- The digital economy, biometric tracking, and AI-driven social credit systems (like in China) ensure that people remain compliant and economically dependent without the need for whips and chains.

One Master for Another

In the 1860s, African Americans were freed from physical bondage, but society as a whole was quietly being placed under a new form of control. The elite ruling class simply traded one system of slavery for another, exchanging direct ownership of people for debt, wage dependence, and centralized governance.

The illusion of freedom keeps people from recognizing their enslavement. Just as physical slaves had to be conditioned to accept their status, modern individuals are trained to believe they are free, even as they work endless hours, pay relentless taxes, and remain trapped in cycles of debt.

The question now is: How does one break free from an invisible prison?

One Response

Dear Liberty Advocate(s),

I do appreciate all of the deep and thought provoking articles that you present, most recently on the presidency of Abraham Lincoln.

His presidency is a topic that does need to have more light shone upon it. We are presented with academia extolling Lincoln as the greatest president (even eclipsing George Washington (although he did have his Whiskey Rebellion)).

We seem to be continually furnished with history noting our political authorities as cherished paradigms of leadership. But in actuality, as you have shown, they are not.

I do believe that we are presently experiencing presidential directives and policies (altruistic though they may appear to be) that will accelerate unitary executive actions to our detriment now and into the future.