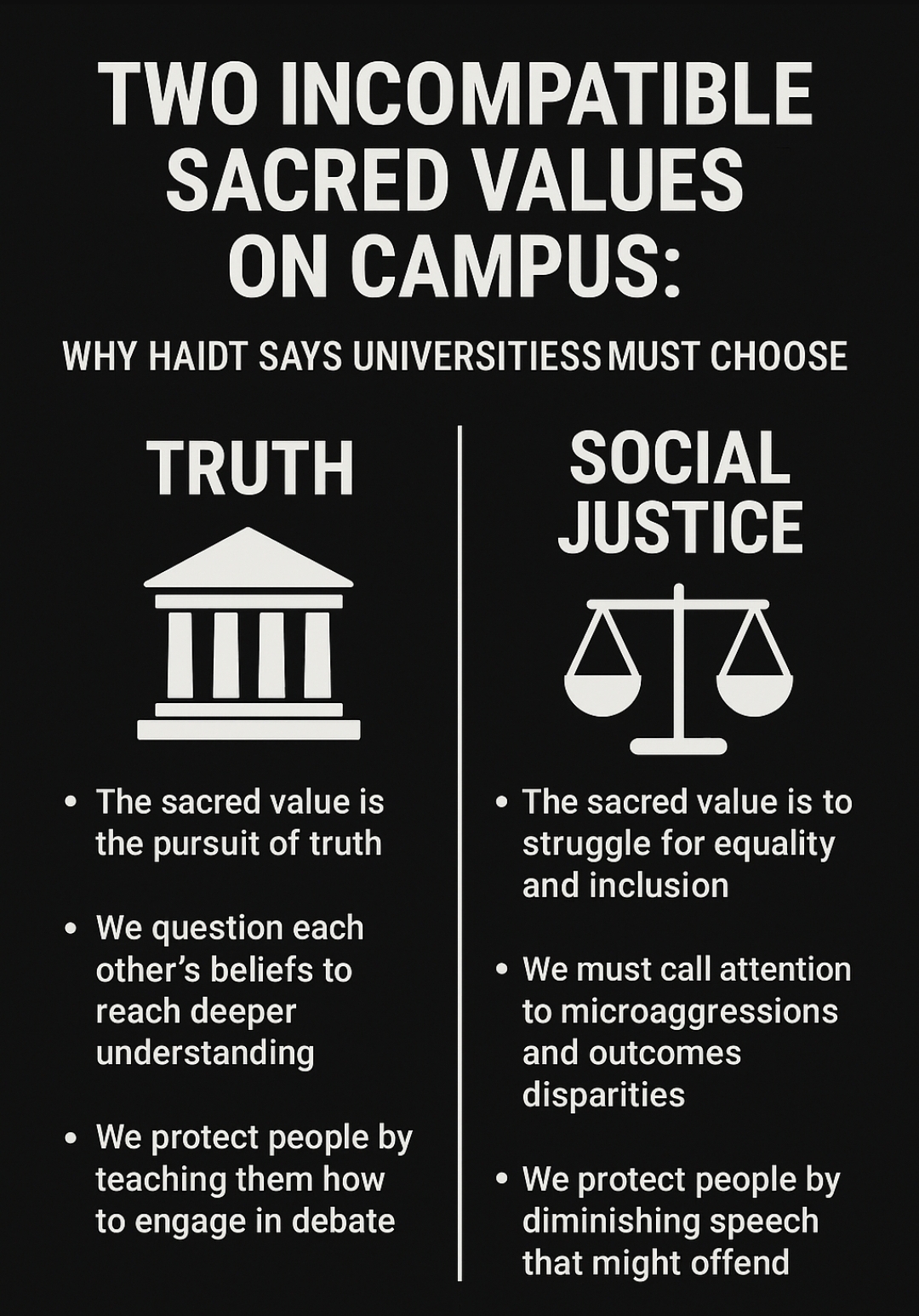

In a packed lecture at Duke University, social psychologist Jonathan Haidt advanced a stark claim: modern American universities are animated by two competing sacred values—Truth and Social Justice—and the institution cannot hold both as its highest purpose without tearing itself apart. The talk, “Two Incompatible Sacred Values in American Universities,” offers a brisk tour through moral psychology, institutional incentives, and campus culture. Whether you end up agreeing with his prescription or not, Haidt’s argument is a clarifying diagnosis of why higher education feels so volatile—and what to do about it.

Mill or Marx? The Foundational Choice

Haidt structures the dilemma with two 19th-century signposts:

- John Stuart Mill (Truth): We only really “know” our own side when we can refute the best arguments against it. A Millian university maximizes viewpoint diversity, debate, and institutionalized disconfirmation—norms that force rival perspectives to collide so error can be found and corrected.

- Karl Marx (Change): “The philosophers have only interpreted the world; the point is to change it.” A Marxian university treats scholarship as an instrument for justice, prioritizing activism and the transformation of social structures.

Haidt’s claim is not that social justice is unimportant. It’s that a university needs one telos—one lodestar. He argues that when Truth and Social Justice are co-sovereigns, truth-seeking gets bent toward preferred conclusions, and justice efforts become less effective because they’re no longer anchored in rigorous error-correction.

Telos: Why Purpose Matters

Borrowing Aristotle’s notion of telos (end/purpose), Haidt notes that we evaluate professions by their core aim: medicine aims at health; law at justice; scholarship at truth. When another value hijacks that aim—say, profit corrupting medical decisions, or a political cause corralling research questions—the field degrades.

He gives the historical case of the 1960s Sugar Research Foundation shaping “fat vs. sugar” science, with downstream policy and public-health harm, to illustrate how telos corruption leads to pleasing falsehoods with real-world costs. His warning: the same failure mode can occur when “social justice” displaces “truth” as the working telos of scholarship.

Why We Need Institutionalized Disconfirmation

The psychological core of the talk is simple and humbling: humans reason to win, not to find truth. We ask “Can I believe it?” when we want something to be true, and “Must I believe it?” when we don’t. This motivated reasoning is universal—professors are not exempt.

The only reliable antidote is institutionalized disconfirmation: adversarial review, genuine viewpoint diversity, and norms that reward refutation. Haidt argues that from the mid-1990s onward, many humanities and social-science departments became politically homogeneous (left-leaning at ratios of 17:1 and higher), weakening the “marketplace of ideas” and making pleasing errors harder to catch and correct.

Result for students: strong convictions, weak justifications, and a pervasive fear of speaking.

Result for faculty: topic herding, caution, and chilled pedagogy.

Sacralization and the Rise of Victimhood Culture

Haidt draws on Émile Durkheim: groups cohere by sacralizing objects and ideals. On many campuses, he says, “the victim” has become sacred—not in the sense of undeserving respect, but in the stricter sociological sense that minor affronts trigger major responses akin to blasphemy. He cites the vocabulary shift toward microaggressions, triggering, and demands for safe spaces, arguing this has morphed into a new moral culture: victimhood culture.

Key features:

- High sensitivity to slights, including unintended ones.

- Appeals to authority to punish offenders.

- Status by advocacy, especially for those defending sacred groups.

Haidt’s worry is not compassion fatigue; it’s fragility. He pairs this shift with antifragility (Taleb): systems and people grow strong through manageable stress. If students are over-protected from difficult ideas, they graduate less resilient and less prepared for the conflict and criticism of adult life.

Blasphemy Laws by Another Name

To show how sacralization constrains inquiry, Haidt revisits controversial episodes (e.g., Larry Summers’s remarks on gender variance in ability distributions and women in STEM). His point is not that any single hypothesis is correct; it’s that some hypotheses become unsayable, even as questions to test. When certain premises are beyond challenge—“racism/sexism are endemic,” “victims play no causal role,” “equal outcomes prove equal opportunity”—the research toolkit shrinks. Correlation gets mistaken for causation; disparate outcomes are read as disparate treatment by default. That’s a recipe, he argues, for misdiagnosis and policy failure.

Memorable line he teaches students: “Disparate outcomes do not imply disparate treatment.” They are a signal to investigate, not a shortcut to blame.

Justice vs. Equal Outcomes

Haidt distinguishes between two projects:

- Justice as the fight against disparate treatment (discrimination). He embraces this as essential.

- Social justice (as practiced) as the pursuit of equal outcomes across groups, regardless of inputs or choices. He warns this often requires injustice (e.g., manipulating discipline rates to match group percentages) and undermines credibility.

For Haidt, the paradox is decisive: Justice depends on truth. You can’t fix what you won’t examine with all the tools on the table.

The Schism Has Already Begun

Haidt doesn’t call for uniformity; he calls for honesty. Some institutions now define themselves explicitly around Social Justice; others (like the University of Chicago) reaffirm free expression and the primacy of Truth. His proposal is to make the distinction explicit so students can freely choose: a “Social Justice University” or a “Truth University.”

He offers three practical steps any “Truth-first” campus can adopt:

- Chicago Principles on free expression.

- Non-obstruction protest policies (protest, don’t shut down).

- Viewpoint diversity as part of diversity commitments.

The Strongest Parts of Haidt’s Case

- Psychological realism: Motivated reasoning is a bipartisan human feature; designed friction is the only fix.

- Antifragility insight: Shielding students from hard ideas is anti-educational.

- Toolbox defense: If you ban certain hypotheses because they’re uncomfortable, you guarantee worse answers.

- Integrative justice: By insisting that justice requires truth, he offers a bridge—not a negation—of moral aims.

Where Reasonable Critics Push Back

- False dichotomy? Many scholars argue institutions can prioritize truth while openly committing to justice as an outcome of truth-seeking (e.g., widening access, measuring bias rigorously, testing remedies).

- Context and proportionality: Not all departments or campuses share the same ideological tilt; the variance matters.

- Policy design details: Discipline and hiring examples are complex; local implementation often decides whether a justice policy yields fairness or perverse incentives.

- Power and history: Some say “neutral disconfirmation” can still reproduce bias if power asymmetries shape who speaks, who gets hired, and which ideas get funded.

These counterpoints don’t nullify Haidt’s core concerns; they pressure-test them—and by his own Millian standard, that’s healthy.

A Practical Synthesis

You don’t have to become a “Social Justice University” to advance justice, and you don’t have to deny injustice to protect truth. A campus that wants both should:

- Name the telos: Truth. Say it out loud. It anchors everything else.

- Codify disconfirmation. Use hiring clusters, debate formats, and peer-review norms that guarantee live dissent in the room.

- Teach antifragility. Build pedagogies that expose students to disagreeable arguments and coach them in refutation, not avoidance.

- Measure what matters. Treat disparities as hypotheses to test, not verdicts. Use experiments, natural experiments, and careful causal inference.

- Separate people from claims. Uphold personal dignity while allowing maximal contestation of ideas—including sacred ones.

- Reward fair-mindedness. Promotion and tenure criteria can recognize steel-manning, replication, and constructive engagement across divides.

This is, in effect, a Mill-plus model: put Truth first, and pursue justice as the fruit of better, braver, more falsifiable work.

The Vote That Matters Most

At the end of the Duke event, Haidt asked the audience which telos they wanted for their university. Hands overwhelmingly went up for Truth. That moment captured his thesis: clarity precedes community. A campus that knows its purpose can argue fiercely inside a shared frame; one that equivocates invites permanent culture war.

We can honor genuine moral aims—dignity, equality under law, compassion for the vulnerable—without sacralizing them into blasphemy shields. The university’s unique contribution to a democratic society is not to mirror its passions but to refine them—to distinguish what feels true from what is true, so our pursuit of justice stands on rock and not on sand.