Core thesis (in plain English)

Gatto says America’s mass, compulsory, age-graded, test-driven school system was not built to educate free people. It was engineered—consciously—to sort, pacify, and manage the population for the convenience of government planners and corporate patrons. What looks like “school” from the outside is, in his telling, a social-control technology whose routines (bells, grades, tracks, standardized tests, age segregation, seat time) train habits of dependence, obedience, and consumerism.

What he “uncovers” (the big reveals)

1) Imported design: the Prussian management model

- Origin story: In the 19th century, American reformers (e.g., Horace Mann) admired Prussian schooling—centralized, compulsory, age-graded, teacher-directed—because it produced uniformity, docility, and predictable citizens.

- Why that mattered: Gatto argues this model spread precisely because it works for administrators, not because it grows independent minds.

2) The administrative revolution in U.S. schooling

- From local to centralized: He traces how a web of university “education” departments, state bureaucracies, and national associations displaced family, church, and town control of learning.

- Key mentality: Early 20th-century administrators (he cites figures like Edward Thorndike and Ellwood Cubberley) pushed “social efficiency”—the idea that schools should sort people into roles the economy needs, not cultivate wisdom.

- Age-grading & credits: The Carnegie Unit (seat-time as the currency of learning) and age segregation made factory-style schooling the default.

3) Philanthropy as steering wheel (Rockefeller/Carnegie/Ford)

- Follow the money: Gatto claims major foundations shaped curricula, teacher training, and testing to produce “reliable” workers and consumers.

- How that looks: Endowing teacher colleges, funding “model” districts, underwriting national testing/measurement, defining “standards”—all framed as progress, but, he argues, nudging schooling away from autonomy and toward compliance.

4) The IQ/testing/eugenics pipeline

- Sorting at scale: Importing IQ tests (Army Alpha/Beta; Binet repurposed by U.S. testers) let schools rank, track, and stigmatize children early.

- The deeper point: Once labeled, students accept their “place,” which dovetails with eugenics-era thinking about “fit” and “unfit.” Gatto’s claim: testing became the scientific aura for social sorting.

5) “Reading reforms” that break reading

- The method fight: He argues the “look-say/whole-word” method—popularized via foundation-funded colleges and basal readers—manufactured reading problems (what parents would later call “dyslexia”), creating lifelong school dependence.

- Why that matters: If you hobble reading, you hobble self-education—the foundation of a free citizenry.

6) The invention of adolescence & the lengthening of childhood

- Keep kids off the real stage: Compulsory attendance + child-labor bans + a culture of “adolescence” keep teens out of productive life and inside institutions.

- Behavioral lesson: The longer you’re trained to wait for permission, the more normal it feels to live that way as an adult.

7) The hidden curriculum as habit training

Beyond the official subjects, the daily mechanics of school teach:

- Confusion: Knowledge chopped into disconnected units on a bell schedule.

- Class position: Tracking/labels tell you where you belong.

- Indifference: Bells interrupt everything; nothing merits deep focus.

- Emotional & intellectual dependency: Experts decide what counts; approval comes from above.

- Provisional self-esteem: Your worth rides on grades and stickers.

- Surveillance: Privacy is suspect; you behave because you’re watched.

(He develops this “seven lessons” idea elsewhere; in Underground History he expands the archive and genealogy behind it.)

8) School as a feeder for consumer culture

- From liberty to lifestyle: Once families and local mentors are displaced, corporate media and advertising (the Bernays era onward) step in.

- Result: Graduates fluent in brands and passive entertainment, but thin on history, logic, craftsmanship, or civic courage.

How he argues it (Gatto’s method)

- Archival quotations & memos: He stitches together speeches, foundation papers, administrative reports, and early 20th-century “social efficiency” literature to show intent, not mere accident.

- Historical vignettes: Prussia, Massachusetts 1852 compulsion, the rise of teacher colleges, the Committee of Ten/15, the Gary Plan, IQ testing, basal readers—each becomes a case study in design choices.

- Teacher’s-eye narrative: As an award-winning NYC teacher, he narrates how real kids respond when you suspend the machinery (no bells, no grades for a spell, real projects, apprenticeships). He reports they wake up—fast.

What he says this system actually produces

- Shallow literacy & math: Just enough to fill forms, consume, and comply.

- Fragile attention & learned helplessness: Twelve years of ring-a-bell/ask-permission.

- Civic amnesia: Little history, less rhetoric/logic, minimal practice in real self-governance.

- A labor pool in “tracks”: Early labels and courses channel life chances.

What he wants Americans to see (the warnings)

- This was engineered. If the outcomes repeat everywhere, they aren’t “bugs.”

- More school ≠ better citizens. Adding hours/years deepens dependence unless the structure changes.

- Testing is policy, not science. It narrows thinking and legitimizes tracking.

- The cost is liberty. A population habituated to surveillance, credentials, and compliance is easy to steer—politically and commercially.

What he urges as remedies (inside and outside the system)

- Give back time. Reduce seat-time/homework; protect long, uninterrupted blocks for deep reading, making, and service.

- Apprenticeships & real work. Every teen should produce things someone actually needs; let mastery, not worksheets, confer status.

- Mixed-age learning & mentorship. Collapse age silos; recover neighborhood knowledge networks.

- Portfolio over ranking. Assess by products, performances, and public contribution, not bubbles.

- Parent sovereignty. Reclaim authority over time, media, mentors, and—in many cases—homeschool/microschool/unschool.

- The lost arts: Bring back logic, rhetoric, grammar, shop/crafts, gardening, home economics, first aid—capacities that anchor independence.

How to read him (and common pushbacks)

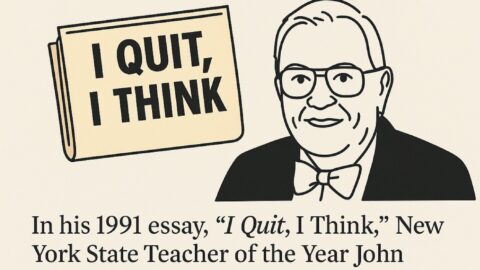

- Tone: He’s a polemicist with a teacher’s eye and a historian’s scrapbook—rich in quotes and connections.

- Critiques you’ll hear: He overstates Prussia’s influence; he romanticizes pre-compulsory literacy; he’s too sweeping about foundations; he’s too hard on Dewey/Thorndike.

- Even so: Across the spectrum, many concede his strongest point: institutional design shapes character. What schools practice daily becomes what students practice lifelong.

A quick “field guide” to his recurring themes

- Design beats intention: Good teachers can’t fully overcome a bad system.

- Monopoly time: Whoever controls children’s time controls their formation.

- Literacy = self-rule: Anything that blunts reading/writing/reasoning blunts citizenship.

- Small is human: Families, shops, farms, parishes, clubs, town halls—thick local life is where real education happens.

- The test of schooling is adulthood: Can graduates build, repair, deliberate, persuade, serve, and self-educate?

Bottom line: Underground History is Gatto’s case that American schooling was deliberately re-tooled to produce predictable, manageable populations. He’s revealing the architecture—who designed it, how it works, and why the results are so consistent. His warning is civic, not merely educational: if we want a nation of free adults, we must rebuild learning around time, mentors, mastery, and genuine responsibility, not bells, ranks, and tests.