The Question That Matters

Late at night, before the experiment that will transform him, Steve Rogers asks the question every leader should: “Why me?”

Dr. Erskine’s reply—“That is the only question that matters”—moves the scene from technology to theology of character. The serum isn’t a creator; it’s a multiplier. It doesn’t manufacture virtue; it amplifies whatever already lives in the soul. This is why the moment isn’t about laboratory genius but moral selection. The real test isn’t of muscle, but of motive.

Erskine is drawing a hard line between capacity and credibility. Capacity asks, Can you do it? Credibility asks, Should you be the one to do it? History is littered with leaders who passed the first test and failed the second—gifted, driven, efficient, and ultimately dangerous, because power magnified ambition faster than conscience.

“Why me?” is the x-ray question that exposes intent:

- Do you want power to serve, or to be seen?

- Will strength protect the vulnerable, or punish inconvenience?

- When orders clash with conscience, which one wins?

By centering motive, Erskine reframes leadership as stewardship. Steve is chosen precisely because he knows the cost of strength—he’s been on the losing end of it. The weak man who becomes strong tends to guard that strength; the strong man who never knew limits tends to spend it.

This scene also gives us a universal hiring rubric—useful in teams, institutions, and politics alike: select for truthfulness, restraint, teachability, and loyalty to the mission over self. Skills can be trained; character must be tested. If your filter only measures talent, you’ll reward charisma over conscience and build brittle systems around unstable cores.

In short: power reveals. If you want just outcomes tomorrow, choose just people today. The serum—like authority, money, platforms, or algorithms—will not fix anyone. It will show them. Hence Erskine’s insistence: first prove the heart, then hand over the shield.

The Fall of Erskine’s Homeland

Erskine remembers Augsburg—his people, his streets—and how the Nazis first conquered themselves. The tanks came later. The early surrender was moral: a slow erosion of courage, truth, and neighbor-love under the weight of fear and humiliation. Authoritarianism rarely arrives as an invading army; it seeps in as a bargain—give us your conscience, and we’ll give you comfort.

After World War I, Germany was exhausted: economically battered, politically fractured, spiritually adrift. Into that vacuum, Hitler offered a potent blend of pageantry, purpose, and pride. The “marching and the flags” did more than decorate rallies; they supplied meaning. Spectacle replaced substance, belonging replaced belief, and emotion outvoted reason. People didn’t wake up one morning as oppressors; they slid—one justified compromise at a time.

Mechanics of the slide:

- Wound → Want: National humiliation creates a craving for decisive leadership.

- Myth → Mobilization: Grand stories of destiny drown out inconvenient facts.

- Scapegoat → Simplicity: Complex problems are reduced to a hated “other.”

- Emergency → Exception: Temporary measures become permanent norms.

- Uniform → Unity: Symbols stand in for virtue; conformity masquerades as character.

Lesson: Freedom is first an inward discipline—habits of honesty, restraint, and responsibility—long before it is an outward arrangement of laws. When a nation forgets that, it trades liberty for leadership and calls it salvation. Constitutions can slow decay, but they cannot save a people determined to outsource conscience. The antidote is cultural: teach citizens to prefer truth over thrill, duty over dopamine, and neighbor over narrative—so when the marching starts, they still know how to stand.

Johann Schmidt: The Mirror of Power Without Virtue

Erskine’s former colleague, Johann Schmidt—the future Red Skull—embodies power without restraint. To Schmidt, the concept of a “superior man” is not myth but mandate. He believes strength entitles him to rule, that destiny is owed to those ruthless enough to seize it. In his hands, science ceases to be a tool of service and becomes a weapon of supremacy.

Where Hitler uses fantasy as propaganda to control others, Schmidt believes his own myth—and that is far more dangerous. The cynic manipulates belief for gain; the fanatic worships his own reflection. Schmidt’s obsession with perfection is idolatry disguised as destiny: the worship of human potential stripped of humility and moral boundary.

When he takes Erskine’s unfinished serum, it “makes him stronger,” but it also amplifies the rot already within him. His outward mutation—skin stripped away to reveal a red skull—is not punishment but revelation. His form mirrors his soul: disfigured by pride, consumed by self-deification. The serum does not create the monster; it uncovers him.

“The serum magnifies what’s within. Good becomes great; bad becomes worse.”

That single line distills the peril of all unchecked power. Every invention, ideology, or institution follows the same law: power reveals character. Technology does not redeem; it exposes. The same tool that heals the sick can enslave the free, depending on the heart that wields it.

Modern parallels abound. Artificial intelligence, social media, and state surveillance are our modern serums. They amplify human nature—our compassion or our cruelty—at exponential speed. When guided by conscience, they connect and enlighten; when driven by vanity or greed, they manipulate and divide. The problem is not the tool but the temperament of the hand that holds it.

Erskine’s warning thus becomes prophetic: the world’s future will hinge not on who controls the technology, but on who deserves to. The moral question remains unchanged across centuries:

When power is placed in our hands—be it a serum, a platform, or an algorithm—will it reveal our humanity or our hubris?

Why Steve Rogers Was Chosen

Steve Rogers is small, frail, and perpetually underestimated—the man who never wins the fight but never walks away from it either. Every bruise on his body has been a teacher, carving into him a reverence for strength—not the desire to dominate, but the duty to protect.

When Erskine tells him,

“A strong man who has known power all his life may lose respect for that power. But a weak man knows the value of strength—and knows compassion,”

he defines the essence of moral leadership. Strength that has never tasted limitation easily becomes arrogance; power without pain forgets mercy. But the man who has struggled, who has known vulnerability and injustice firsthand, carries empathy as his moral compass.

Steve’s courage is not reactionary bravado—it’s conscience in motion. He doesn’t fight because he enjoys conflict; he fights because silence in the face of cruelty feels like complicity. That’s why even before the serum, he stands up in alleys, in theaters, in recruitment lines—everywhere injustice sneers at weakness. His body may lose, but his spirit refuses surrender.

This is the paradox of true strength:

- The physically weakest man is chosen to carry the greatest power.

- The man who has been protected by no one becomes the protector of all.

- The one who has never been feared learns never to inspire fear in others.

Steve’s moral clarity flows from his suffering. Every rejection and beating shaped his internal code: that might without mercy is just another form of tyranny. His humility is not meekness—it is self-awareness sharpened by hardship. When given power, he will remember what it felt like to be powerless, and that memory will become his restraint.

This is what separates heroes from rulers, and guardians from conquerors. Many crave strength for validation; Steve values it for vocation. He does not see power as a right, but as a responsibility to shield, not to shine.

In a world obsessed with dominance and visibility, Steve represents the rare kind of person who understands that the worth of strength lies not in what it can take, but in what it can protect.

That is moral maturity: motive before might, conscience before conquest.

The Promise

Erskine’s final request before the procedure:

“Whatever happens tomorrow, promise me one thing—that you will stay who you are. Not a perfect soldier, but a good man.”

Erskine is drawing a line that every age tries to blur: execution vs. ethics.

A perfect soldier optimizes for orders, optics, and outcomes. A good man answers first to conscience, then to command. One maximizes effectiveness; the other safeguards ends and means.

Why it matters: Power expands options and excuses. Without an internal governor, success becomes its own justification. Erskine’s charge makes Steve take a vow before the serum so that the vow can govern after the serum.

Perfect Soldier vs. Good Man (decision hierarchy):

- Authority: Chain of command vs. Moral law above men

- Metric: Did it work? vs. Was it right?

- Loyalty: Institution first vs. People and principle first

- Courage: To advance vs. To refuse

- Obedience: Compliance vs. Conscience-led obedience (with a right to defy)

The promise as guardrail:

- It pre-commits Steve against mission creep (“win at any cost”).

- It authorizes dissent when orders conflict with justice.

- It centers the vulnerable as the purpose of strength (his toast “to the little guys” is the practical clause of the vow).

Crisis test (how this plays out later):

- When institutions are compromised (S.H.I.E.L.D./HYDRA), the perfect soldier executes; the good man exposes.

- When a friend is framed (Bucky), the perfect soldier neutralizes the threat; the good man pursues the truth.

- When oversight demands pre-permission (Sokovia Accords), the perfect soldier signs; the good man keeps the right to choose.

Modern echo: Titles, badges, and dashboards can make us “perfect soldiers” in business, tech, and government—high output, low reflection. The antidote is Erskine’s rubric: truthfulness, restraint, responsibility to the weak, even when it slows the sprint or costs the win.

Practical adoption (for real teams):

- Write a one-line pre-commitment for power: “We will not do what works if it violates what’s right.”

- Build refusal routes (protected channels to say no).

- Evaluate leaders on how they achieve outcomes, not just that they do.

- Celebrate principled restraint as much as bold initiative.

Erskine’s final words are the compass for every Captain America story that follows—and a blueprint for ours: Power must serve principle, not ego; conscience must lead the charge, not the command.

The Toast: “To the Little Guys”

Their brief toast seals the theme. Erskine and Steve don’t drink to victory, but to humility—to the forgotten, the small, and the ordinary. It’s a moment drenched in quiet reverence, not triumph. The toast isn’t about conquest; it’s about character. They raise their glasses not in celebration of what Steve will become, but in honor of what he already is: a man whose heart is larger than his frame.

The scene reminds us that greatness is rooted in gratitude. Erskine, who has seen power corrupt geniuses and tyrants alike, knows that humility is the only soil in which virtue can safely grow. His toast “to the little guys” is more than a gesture—it’s a creed. It’s a recognition that real strength exists not in domination, but in service; not in being seen, but in remembering the unseen.

In that moment, Steve represents what every society needs but rarely rewards: the humble man with unshakable convictions—the one who fights not to prove himself, but to protect others. He is the antidote to the arrogance that builds empires and the indifference that destroys them. His humility doesn’t make him weak; it makes him trusted.

The irony is profound: the man who never had power becomes the safest one to hold it. The toast becomes prophetic—a quiet covenant between generations—that strength without humility is dangerous, and that the world’s hope rests not in perfect soldiers or clever rulers, but in good men who remember what strength is for.

The Timeless Lesson

This quiet conversation defines the entire moral architecture of Captain America—and, by reflection, the moral crisis of our own age. Erskine’s laboratory becomes a mirror for every civilization that has ever grappled with the question of what power does to the human heart. His words echo far beyond 1940s Europe; they speak into the digital age, where humanity once again plays with forces it scarcely understands.

Technology is our new serum. It magnifies what we already are. It has given ordinary people extraordinary reach—but not necessarily extraordinary wisdom. We no longer lift cars or hurl shields; we shape minds, markets, and nations with a tap of a screen. The serum is now code and algorithm, data and dopamine. If we are vain, technology multiplies vanity; if we are greedy, it monetizes greed; if we are compassionate, it scales mercy to millions. It has no conscience of its own—it merely reflects the one holding it.

This is why Erskine’s warning is prophetic: “Good becomes great; bad becomes worse.” The digital world does not create evil—it amplifies intent. Every tweet, every viral video, every new innovation functions like a moral loudspeaker, broadcasting what’s inside us to the world. The danger isn’t the technology; it’s the temptation—the intoxicating illusion that influence is the same thing as integrity.

Politics, too, has its Schmidts. Power-hungry men and women still wrap self-interest in noble language: “destiny,” “progress,” “security,” “the greater good.” Like Johann Schmidt, they cloak ambition in myth, hiding pride behind slogans. They speak of uniting humanity while dividing it, of saving the world while enslaving it to debt, data, or doctrine. The symbols have changed—the skull replaced by the slogan, the uniform replaced by the suit—but the spiritual DNA is the same. It is still idolatry dressed as destiny.

Erskine’s antidote remains the only real solution: Steve’s promise.

“Stay who you are. Not a perfect soldier, but a good man.”

That charge is more urgent now than ever. The greatest danger of our century is not that machines will outthink us, but that they will mirror us too faithfully—that our tools will perfect our vices faster than our virtues. When ambition disguises itself as innovation and corruption wears the mask of opportunity, the only defense is the disciplined conscience.

To “stay who you are” is not passivity—it is moral resistance. It means guarding the inner life from the seduction of metrics, applause, and tribe. It means remembering that goodness is not outdated idealism but the last firewall between civilization and chaos.

Erskine’s conversation with Steve is therefore not just a scene in a superhero story—it is a moral parable for modern humanity:

Power will always expand.

Technology will always evolve.

The question remains the same:

Will we?

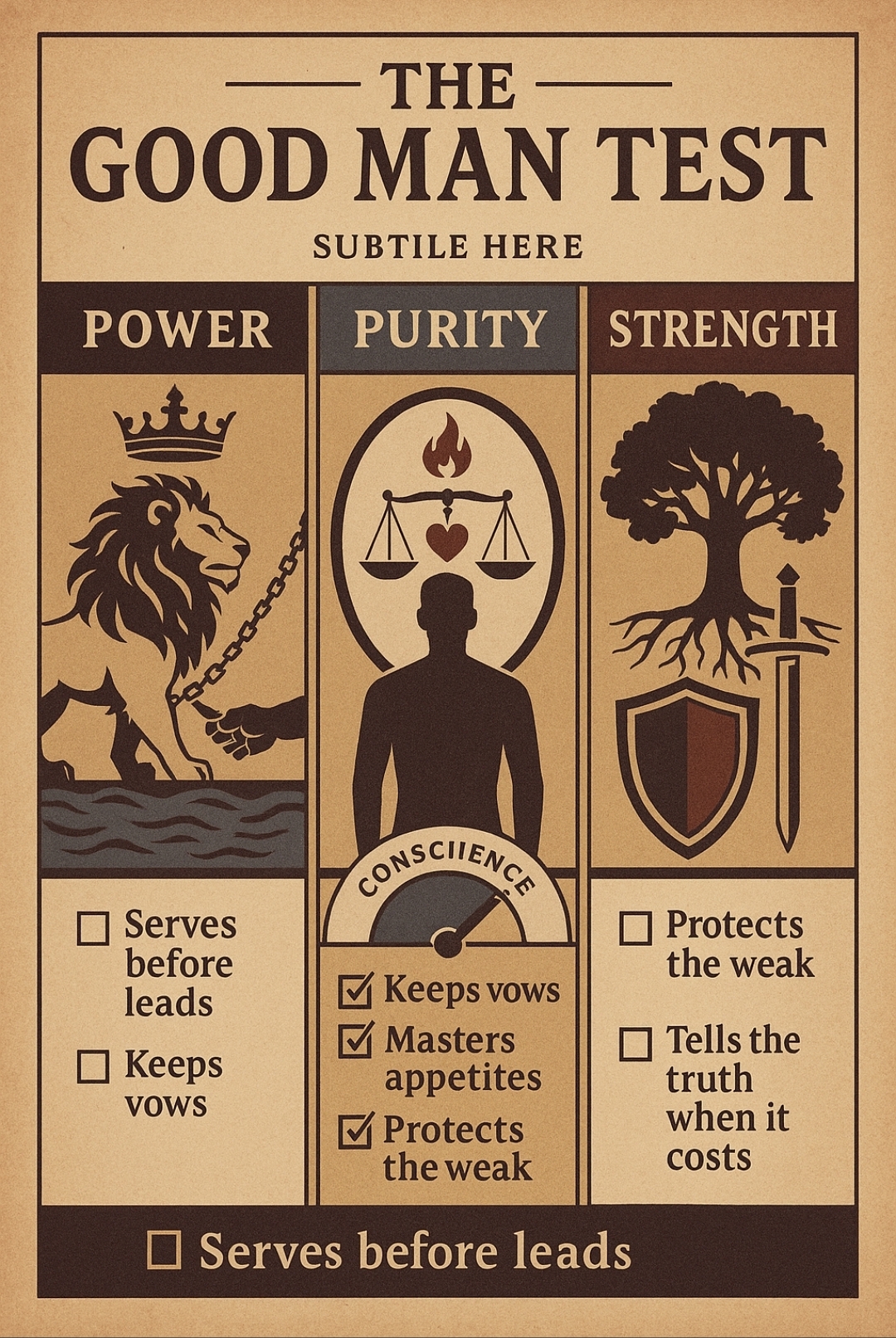

Reflection: The Good Man Test

Every generation must face the same choice. The costumes change, the tools evolve, the flags are redesigned—but the moral dilemma endures:

Will we become perfect soldiers—obedient, efficient, and morally neutral, serving systems that reward compliance over conviction?

Or will we remain good men—courageous enough to think, compassionate enough to feel, and anchored enough in truth to stand when it costs us something?

The “perfect soldier” follows orders, even when those orders wound conscience. He measures success by victory, not virtue; by applause, not integrity. He is the citizen who outsources judgment to the collective, who calls submission “peace” and silence “wisdom.” In every age, empires thrive on such soldiers.

The “good man,” by contrast, carries a heavier burden. He questions, listens, and loves truth more than comfort. He is not defined by strength, but by the direction of strength—by how power passes through him to protect others rather than to glorify himself. His defiance is not rebellion for its own sake; it is obedience to a higher moral law when lesser men bow to convenience.

And so, the serum still amplifies. Every form of power—whether political, technological, or personal—functions as its own modern serum. It exposes the heart beneath the skin. It multiplies what is already present. If pride rules, it will crown pride; if humility reigns, it will elevate virtue.

The question remains the same:

When power finds you, what will it reveal?

Will it show the servant or the tyrant?

The steward or the opportunist?

The man ruled by principle—or the man ruled by impulse?

This is not merely Steve Rogers’ test; it is ours. Every algorithm we design, every law we pass, every platform we build, and every choice we make is a mirror in which our true character appears. Power will always move forward—but it will not move us upward unless conscience leads the way.

The world does not need more perfect soldiers. It needs more good men—people who remember what Erskine saw that night:

That the mightiest weapon in any age is not the serum, the science, or the system—

It is the soul that remains good when it no longer has to.