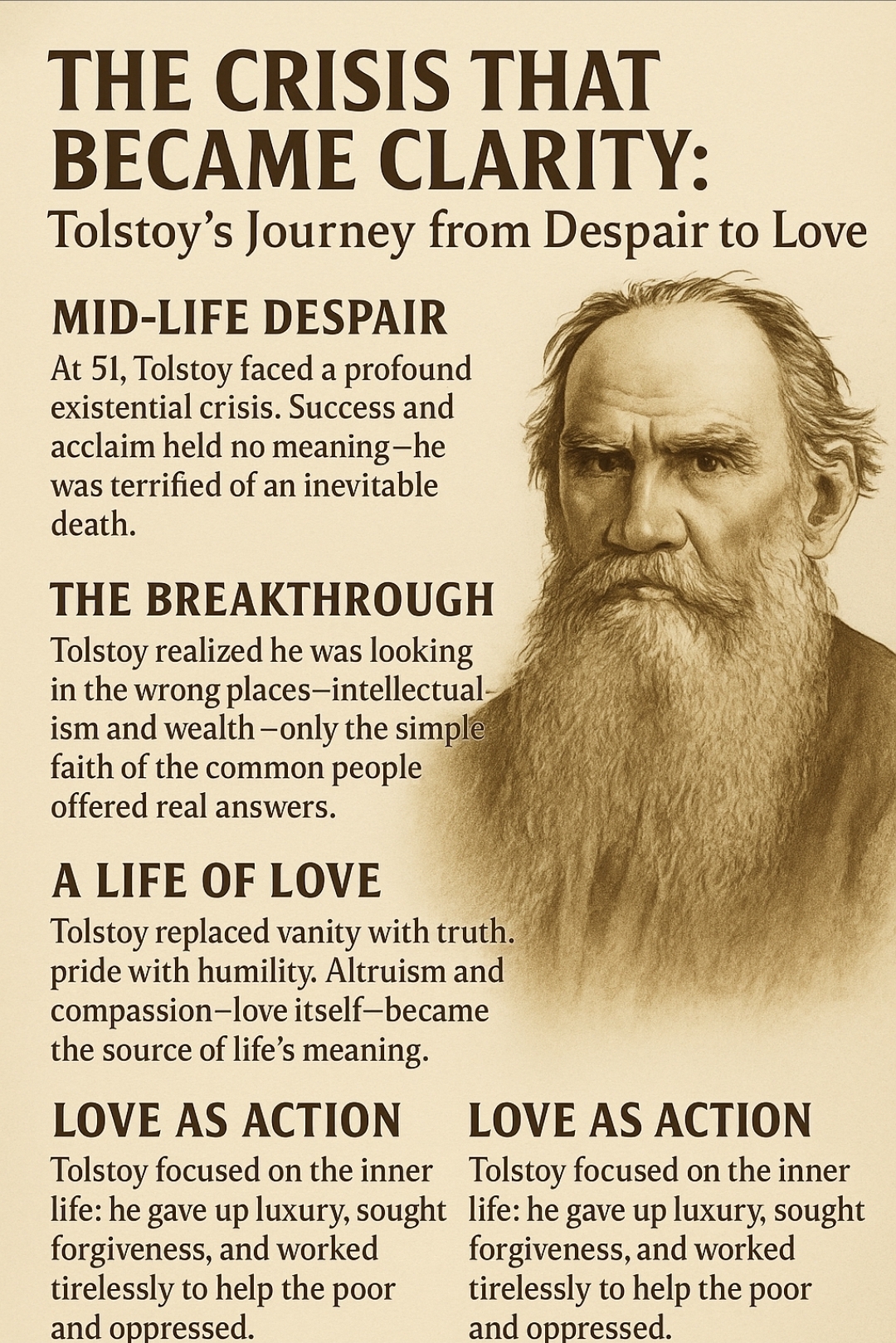

A Life of Success—And Emptiness

Imagine standing at the height of worldly success: wealth, fame, influence, family, and achievement. Now imagine being gripped by the terrifying thought that none of it means anything. This was not fiction, but the lived reality of Leo Tolstoy, one of history’s greatest writers and thinkers.

Despite his literary triumphs—War and Peace, Anna Karenina—and his privileged life as Russian nobility, Tolstoy confessed that he could not go on living. He realized that death would eventually erase everything he had built: his achievements, possessions, and even memories of his loved ones. His private writings describe this haunting vision as dangling over a bottomless pit—clinging desperately to a branch, with death waiting below.

The Awakening Behind the Crisis

Yet Tolstoy’s despair was not simply weakness—it was the beginning of awakening. He recognized that his life was built upon foundations incapable of answering the deepest human questions. What is the point of all this? Why live, if everything is destined to be erased?

He looked around at his peers—the elites, the educated, the powerful—and found them just as lost. Many coped through distraction or intoxication, but few dared to confront the void directly.

The Limits of Reason and Science

Tolstoy tested the answers of his age. Logic, science, and reason had fueled modern progress, but when applied to meaning, they failed him. Darwin could explain how life evolved, but not why it existed. Mathematics could measure the age of the stars, but not the purpose of a human heartbeat.

Other thinkers, like Schopenhauer, declared that human life was nothing but a pendulum swinging between suffering and boredom. Tolstoy refused to stop there. He wanted more than bleakness; he searched for hope.

Learning from the Humble and the Faithful

The surprising turn came not from philosophers but from peasants. Tolstoy saw that the farmers and laborers around him—people with little education or wealth—lived with a peace and purpose that eluded the elite. Their secret was faith.

This was not mere religious ritual, but a living, breathing connection to something beyond the material. Inspired, Tolstoy began studying world traditions: Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, and Greek philosophy. He read the Gospels, the Bhagavad Gita, and the teachings of the Buddha—not as dogma, but as guides for living.

Insights Across Traditions

- From Christianity, especially the Sermon on the Mount, he found radical simplicity: love enemies, turn the other cheek, give without expecting in return.

- From Buddhism, he learned that suffering is rooted in attachment, and liberation comes through letting go.

- From the Bhagavad Gita, he discovered dharma: a life aligned with inner truth and responsibility, rather than external outcomes.

In these traditions, he saw that meaning was not built on ego, achievement, or status—but on connection, humility, service, and love.

Transformation of a Life

Tolstoy acted on what he learned. He gave away wealth, wore peasant clothing, worked with his hands, and redirected his writing. Instead of aristocratic drama, he wrote essays on love, nonviolence, and spiritual awakening.

“Everyone thinks of changing the world,” he famously wrote, “but no one thinks of changing himself.”

His radical shift would go on to influence others, most notably Mahatma Gandhi, who credited Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God Is Within You as a central inspiration for his philosophy of nonviolence and resistance.

Exposing Society’s Illusions

Tolstoy became convinced that modern life was structured to avoid meaning. People lived as if they would never die—and died as if they had never lived. Institutions, whether political, economic, or even religious, distracted people from truth by offering rules instead of wisdom, fear instead of love, and obedience instead of understanding.

His solution: bypass the systems, and return to the quiet voice of conscience within.

Death as Teacher, Not Terror

The haunting specter of death, which once drove Tolstoy to despair, became his teacher. He came to see death not as annihilation, but as completion. Life’s task was not to build monuments or reputations, but to align outer living with inner truth.

The question became: Does this action come from fear—or from love?

The Final Realization: Love as Life’s Meaning

In the end, Tolstoy concluded that love (agape) was not just an emotion, but the very meaning of life itself. Love was the only principle strong enough to withstand suffering, death, and the chaos of existence.

“Everything I understand,” he wrote, “I understand only because I love. Everything exists only because I love.”

For Tolstoy, true love required the death of the false self. Ego could desire, possess, or seduce—but only in humility could one truly love. Love, lived through (moral clarity) compassion, humility, and truth, was the essence of freedom.

The Quiet End of a Great Life

In his final days, Tolstoy left his estate secretly, seeking solitude. He died quietly in a small railway station—not in despair, but in clarity. He had walked through every illusion life could offer and had chosen instead the path of truth.

He left the world not with final answers, but with the deepest of questions:

- What am I living for that will still matter in a hundred years?

- Is my life aligned with truth, or just with habit?

- What would life look like if love became my first principle?

A Challenge for Us

Tolstoy’s life shows that meaning is not hidden in intellectual brilliance or worldly achievement. It is made, moment by moment, in how we live—with presence, compassion, and love. Fame, possessions, and legacy will pass. Only the love we give endures.

Point-by-Point Breakdown of the Tolstoy Transcript

1. The Crisis of Meaning

- Tolstoy, at the height of success, felt life was void of meaning.

- Despite wealth, fame, and family, he saw death would erase everything.

- He described this state as hanging from a branch over a pit: helplessness, despair, only death below.

2. The Awakening

- This wasn’t just failure—it was the beginning of clarity.

- He realized he had built his life on foundations that could not answer ultimate questions.

- Asked: What is the point of any of this?

- Observed that elites were just as lost, using distraction and intoxication to cope.

3. The Limits of Reason and Science

- Science, logic, and reason couldn’t answer why life exists.

- Darwin explained evolution but not purpose.

- Math calculated the universe’s age but not the heartbeat’s meaning.

- Schopenhauer described life as a pendulum between suffering and boredom, but Tolstoy wanted hope.

4. Learning from the Simple and the Faithful

- Tolstoy turned to peasants, farmers, the uneducated poor.

- Noticed they had more peace and purpose than elites.

- Their secret: faith. Not blind ritual, but living connection to something beyond.

- This led him to explore multiple traditions: Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, and Greek philosophy.

5. Insights from World Traditions

- Christianity: Teachings of Jesus (Sermon on the Mount, loving enemies, giving without return).

- Buddhism: Suffering comes from attachment; liberation from letting go.

- Bhagavad Gita: Dharma—inner duty aligned with truth, not outcomes.

- Across traditions he saw meaning in connection, service, humility, and dissolving ego.

6. Radical Life Transformation

- Tolstoy simplified: gave away wealth, wore peasant clothes, worked with his hands.

- Shifted from novels of drama to radical essays on love, nonviolence, awakening.

- Quote: Everyone thinks of changing the world, but no one thinks of changing himself.

- Gandhi was deeply influenced by Tolstoy’s book The Kingdom of God Is Within You.

7. Facing Society’s Illusions

- Society avoids meaning, chasing distraction, productivity, reputation.

- People “live as if they will never die and die as if they never lived.”

- Institutions—political, economic, even religious—offered rules instead of wisdom, fear instead of love.

- Tolstoy urged bypassing systems, returning to conscience and inner truth.

8. A New Relationship with Death

- What haunted him became a teacher.

- Death = not an end, but the completion of life’s task.

- Life’s task: not monuments but alignment of inner truth and outer living.

- Asked: Does this action come from fear or love?

9. Practices of Spiritual Freedom

- Honesty, silence, simplicity.

- Plant-based diet, renunciation of luxury, manual labor.

- Service to others, education for peasants, resistance to oppression.

- Transformation came not from theory but from daily lived conscience.

10. The Final Realization: Love as First Principle

- Love is life’s meaning—not sentiment, but action.

- Love as truth in action, service, sacrifice, stillness.

- Quote: Everything I understand, I understand only because I love.

- Love was the only force strong enough to hold against suffering, death, and chaos.

11. The Challenge He Leaves Us

- Ego cannot love—it only desires and possesses.

- To love is to die to the false self.

- Highest human life = not brilliance, but moral clarity lived through compassion, humility, truth.

- Tolstoy’s death: left estate secretly, died quietly in a railway station—at peace, with clarity.

12. The Question for Us

- What would your life look like if love became your first principle?

- Legacy, fame, and possessions fade.

- Only the impact of love endures beyond death.