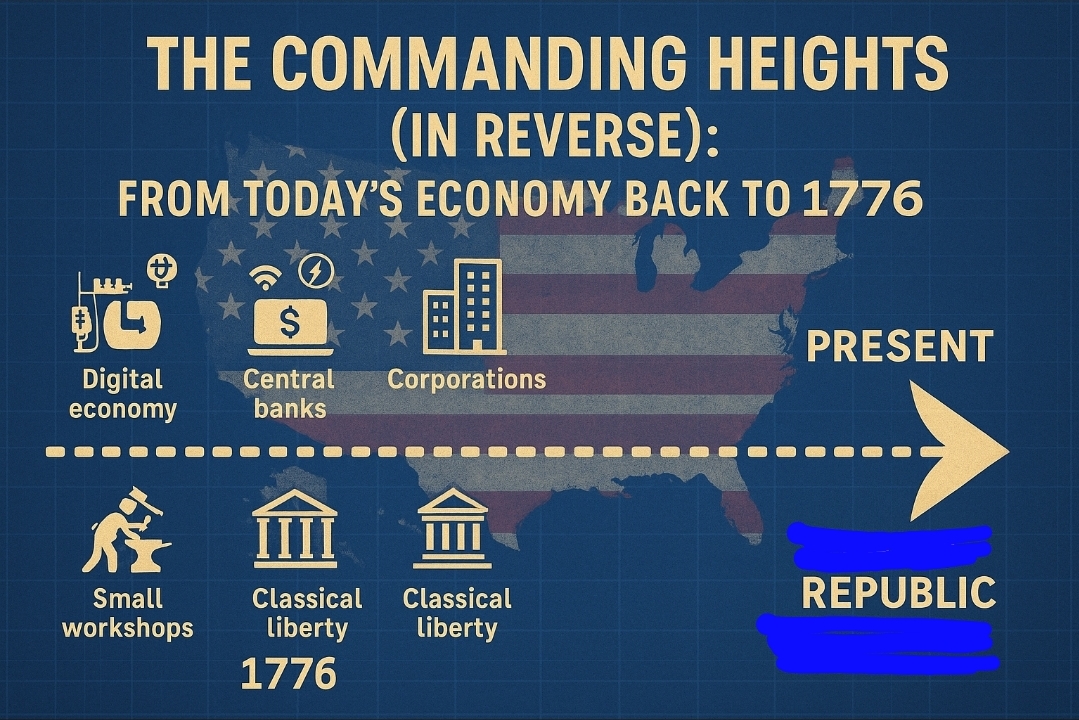

Most of us are born into a system, assume it’s normal, and never see the fights that built it. When you rewind the tape, a pattern pops out: each “modernization” tends to centralize control—money, law, data, and trade—in fewer hands. The dissenters who warned about concentration were often right.

Below is a reverse-engineered tour: starting with today’s stack and walking backward to 1776—showing how the “commanding heights” moved farther from towns and households and closer to boardrooms, capitals, and clearinghouses.

2020s–2000s: The Platform–Central Bank–Security Stack

What you feel today

Platforms as marketplaces

Today a handful of tech giants—Amazon, Apple, Google, Meta—sit between you and almost everything online. Their app stores, search results, and ad systems decide what gets seen and sold. Think of them like private customs houses: to reach customers, sellers must pass through their gates, pay their fees, follow their rules, and accept that the platform can boost or bury you with an algorithm tweak.

Monetary steering

Behind the scenes, central banks try to guide the whole economy by changing interest rates, buying bonds, and signaling what they’ll do next. Cheap money makes borrowing and investing easier; expensive money slows things down. Meanwhile, the biggest banks are treated as too big to fail—if they wobble, everyone worries the whole system could tip, so they get special attention and rescue plans smaller players rarely see.

Securitized everything

Your mortgage, student loan, even a company’s future profits can be bundled and sold as financial products to investors. That means the person who collects your payments may be a fund in another state (or country), not your local lender. The upside is more money flows into loans; the downside is decisions get made far away by people who don’t know you or your town—and who may prioritize spreadsheets over relationships.

Compliance rails

To move money or open accounts you pass through KYC/AML checkpoints—“know your customer” and anti–money laundering rules. Add sanctions lists and payment-network policies, and you get gates that can allow, delay, or block transactions. These rails help fight crime, but they also create single points of control: flip a switch, and someone’s business—or charity—can’t send or receive funds.

Winner-take-most

In digital markets, the more users a platform has, the better it gets—more buyers attract more sellers, which attract more buyers. Those network effects snowball until a few firms pull in most of the customers, data, and cash. It’s convenient—everything’s in one place—but it concentrates power: rules, prices, and visibility are set by a tiny number of companies that everyone else depends on.

Who resisted? Privacy advocates, antitrust reformers, community bankers, open-source/interop folks.

Result: Some guardrails, but the center of gravity remains global + digital + financialized.

1990s–1980s: Hyper-Globalization & Deregulation

Moves

Tariffs fall; WTO/NAFTA and supply chains stretch across oceans

In the late ’80s and ’90s, countries lowered trade barriers and signed big deals like NAFTA and later the WTO rules. Companies could now make parts where it was cheapest, ship them halfway around the world, and assemble products somewhere else. For shoppers this meant lower prices and more choices. For many towns, it meant factories moved and the old “work where you live” model faded as jobs followed cheaper labor and looser rules overseas.

- NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement): Think of NAFTA (started in 1994) as a deal between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico to make trading with each other easier and cheaper. It cut most tariffs (import taxes) on goods crossing their borders and set common rules so companies knew what to expect. Results in practice: car parts might be made in Mexico, engines in the U.S., final assembly in Canada—then sold anywhere in North America with minimal extra fees. Upside: cheaper products, more cross-border business. Downside: some factories moved to where labor and rules were cheaper, so certain towns lost jobs. (NAFTA was later updated as the USMCA in 2020, but the basic idea—easy trade across North America—remains.)

- WTO (World Trade Organization): The WTO (launched in 1995) is like a referee for global trade. Over 160 countries agree to a rulebook: how high tariffs can be, how to treat foreign products, what counts as unfair subsidies, and how to settle disputes. If Country A thinks Country B is breaking the rules, they file a case; panels hear it and can allow penalties if someone’s cheating. Upside: clearer rules and fewer trade wars, which helps companies plan and keeps prices lower. Downside: critics say the rules can favor big multinationals and make it hard for countries to protect certain local jobs or standards.

- Simple difference: NAFTA/USMCA = a regional trade deal (U.S.–Canada–Mexico). WTO = a global club and court for trade rules among many countries.

- How this showed up in everyday life: More stuff on store shelves at lower prices; products built from parts made in several countries; more choice for consumers—but also more pressure on local factories that suddenly had to compete with plants overseas.

How “more pressure” becomes “pushed out” (in plain terms)

- Scale advantage: Global firms run huge plants and buy raw materials in bulk, so their per-unit costs are lower. A local factory can’t match those prices for long.

- Buyer power: Big retailers (think big-box chains) tell suppliers, “Match the lowest global price or lose the shelf.” Local shops don’t have that leverage; local factories lose orders and cash flow.

- Regulatory arbitrage: Multinationals place steps of production where wages, taxes, and rules are cheapest. Locals don’t have that option, so they look “expensive” on paper even if they’re efficient in real life.

- Financing & patience: Global players can run losses to win the market (cheap corporate credit, cross-subsidies). Small factories live month-to-month; a few bad quarters and they’re done.

- Logistics & tech: Container shipping, just-in-time delivery, and global software make it easy to coordinate far-flung plants. What used to be a headache is now routine, so offshoring scales up.

What it does to a town

When the anchor plant closes, paychecks vanish, then diners, hardware stores, and tax revenue fade. Housing values stagnate, schools struggle, and young people leave. Meanwhile, profits and decision-making move up the chain—to corporate HQs and investment funds—enriching a small group far from the community that lost the work.

It’s not all upside for consumers, either

Prices do drop for a while, but you also get less choice of employers, more fragile supply chains (remember shortages), and fewer paths into the middle class if you don’t have a college degree.

If you want the opposite outcome (practical fixes)

- Level the playing field: Enforce antitrust so giant buyers can’t squeeze suppliers to below-cost deals; stop mergers that remove the last local competitor.

- Local first: Public purchasing that prefers regional suppliers when quality/price are close; “value-added” scoring that counts local jobs and resilience, not just sticker price.

- Tie subsidies to promises: If a company gets tax breaks, require clawbacks if it offshores or misses job targets.

- Build local capacity: Support co-ops/ESOPs, supplier clusters, and technical colleges aligned with local industry; help small firms export together.

- Fair trade over free-for-all: Push trade rules that include labor/environment floors so competition isn’t just a race to the bottom.

- Resilience standards: For critical goods (energy, food, medical, defense), require some domestic or regional production and stockpiles.

Global supply chains brought cheaper goods—but the way we structured them shifted power and profits upward, leaving many communities poorer. With better rules and smarter local investing, you can keep the benefits of trade without sacrificing the town that built the economy in the first place.

Deregulation of finance (and telecom/airlines) amplifies competition and consolidation

Governments loosened rules on banks, phone companies, and airlines. At first, prices often dropped and new players appeared. But over time, the strongest firms bought rivals and merged into giants. In finance, looser rules helped create new products and easy credit—until risks piled up in ways few understood. Net result: consumers got some bargains, but market power re-clumped at the top, and financial shocks traveled faster.

“Shareholder value” takes over; buybacks boom

Business culture shifted to worship the quarterly stock price. CEOs were paid in shares, so keeping investors happy right now mattered more than patient, long-term building. Companies used profits—and cheap borrowing—to buy back their own stock, boosting share prices instead of, say, raising wages or investing in new plants. Wall Street cheered; many workers saw stagnant pay, more outsourcing, and a focus on short-term wins over durable growth.

Local effect: Manufacturing towns hollow; capital mobility outpaces worker mobility.

Dissenters: Labor organizers, “fair trade” coalitions, antitrust traditionalists.

1971–1980s: The Dollar Unpegged & Financialization Begins

1971 was the big flip. When the U.S. stopped redeeming dollars for gold, money became fiat (backed by government credibility, not metal). At the same time, oil was priced in dollars (“petrodollar”), keeping global demand for dollars high. With no gold anchor, exchange rates started to float—currencies rise and fall like stock prices—which opened the door to huge, fast money flows across borders as investors chased returns.

Finance remade itself to manage that risk and opportunity. Banks and funds built derivatives (futures, options, swaps) to hedge currency and interest-rate swings; pensions and mutual funds grew into giants; Wall Street’s tools got complex—and powerful. For households and governments, debt became the shock absorber: instead of cutting spending or wages right away, we borrowed—for homes, college, business expansion, and to smooth recessions. Low interest rates made this feel painless for a long time, but it also meant the economy’s health increasingly depended on credit, so when finance wobbles, everything shakes.

There wasn’t a single “go” law—it was a stack of decisions, statutes, court rulings, and rule changes from the 1970s–2000s that, together, let finance scale, innovate, and take on more risk than before. Here are the big hinges, in plain English and rough timeline:

- 1971 – Gold window closed (policy, not a law).

Nixon ended dollar-to-gold convertibility. That set up floating exchange rates and far bigger, faster cross-border money flows—fuel for modern finance. - 1974 – ERISA (pensions) + 1978/1981 401(k) greenlight.

ERISA professionalized pensions; then 401(k) rules let retirement savings pour into mutual funds and markets. Result: a huge pool of institutional money hunting returns, eager users of new financial products. - 1975 – “May Day” on Wall Street (SEC).

The SEC ended fixed stock-broker commissions. Trading went competitive, volumes exploded, and finance became more market-driven (and later more electronic). - 1978 – Marquette Supreme Court decision (credit cards).

Banks could “export” the most permissive state’s interest-rate rules nationwide. Credit card lending boomed; household credit expansion accelerated. - 1980 – Depository Institutions Deregulation & Monetary Control Act (DIDMCA).

Phased out interest-rate caps on deposits (Reg Q) and broadened Fed oversight. Banks competed harder for deposits and pushed into new products. - 1982 – Garn–St Germain Act.

Opened the door to more adjustable-rate mortgages and expanded what thrifts could do—fueling mortgage innovation (and some of the S&L excesses). - Early–mid 1980s – Securitization gets legal plumbing.

- 1984 SMMEA made private mortgage-backed securities legal investments for many institutions (and preempted some state limits).

- 1986 Tax Reform Act created REMICs, the tax-efficient vehicles that made slicing mortgages into bonds easy.

Net effect: your loan could be bundled and sold to investors anywhere.

- 1982 – SEC Rule 10b-18 (stock buybacks).

Gave companies a “safe harbor” to repurchase their own shares—key to the later buyback boom and shareholder-value focus. - 1988 – Basel I (global bank rules).

Not a U.S. law, but U.S. regulators adopted it. Risk weights made highly rated securities capital-efficient, nudging banks toward AAA securitized assets. - 1990 – SEC Rule 144A (private placements).

Made it easier to sell securities quickly to big institutions—greased the wheels for modern capital-markets funding. - 1994 – Riegle–Neal Act (interstate banking).

Let banks branch across state lines. Result: consolidation into national giants. - 1999 – Gramm–Leach–Bliley (repeal of Glass–Steagall partitions).

Allowed one financial holding company to own commercial banks, investment banks, and insurers. Bigger, more complex “universal banks” were born. - 2000 – Commodity Futures Modernization Act (CFMA).

Exempted most over-the-counter derivatives (like credit-default swaps) from traditional regulation. Derivatives markets exploded in size and opacity. - 2004 – SEC capital rule change (CSE program).

Let big broker-dealers use internal risk models and more leverage. It amplified balance-sheet size (and vulnerability) before 2008. - 1996 – Smiley v. Citibank (fees as “interest”).

Helped issuers treat certain fees like interest under usury export rules, further expanding consumer credit revenue models.

Why this mattered:

- The money base got more flexible (post-gold, floating FX).

- Massive institutional pools (pensions/401(k)s) needed yield.

- Laws and rules opened new products (MBS/ABS, derivatives), lowered frictions (144A), weakened structural separations (GLBA), and favored scale (interstate banking).

- Households, firms, and governments increasingly used debt as the shock absorber—easy while rates fell, destabilizing when finance wobbled.

Resistance: “Sound money” voices, community-credit advocates.

Arc: Credit becomes king; Wall Street’s reach into Main Street deepens.

1944–1970s: Bretton Woods & the Managed Order

Design

Right after World War II, the big economies agreed on a money system where currencies were pegged to the U.S. dollar, and the dollar was tied to gold—fixed but adjustable if a country got into trouble. Two new helpers—the IMF (a short-term lender for countries in a pinch) and the World Bank (long-term loans for rebuilding and development)—kept the system from spinning out. With exchange rates mostly stable, trade and investment felt predictable, so factories expanded and global commerce grew without daily currency chaos.

At home, the U.S. paired that global stability with middle-class building blocks: the GI Bill sent millions of veterans to college and helped them buy homes; FHA mortgages made 30-year fixed loans normal; the Interstate Highway System connected markets and suburbs; and strong unions helped turn rising productivity into rising pay. The combo—steady international money + domestic investment in people and infrastructure—delivered a few decades where ordinary families could buy a house, raise kids on one income, and expect wages to track growth. It wasn’t perfect (many communities were excluded by redlining and discrimination), but the basic model was a managed, rules-based order that traded a bit of policy freedom for stability, and used public investment to spread the gains.

Trade-off: Stability via central coordination; rising national corporates.

Dissent: Anti-monopoly progressives warned about oligopoly; civil-rights leaders warned prosperity was unevenly shared.

1930s: New Deal—National Scale Meets Local Crisis

Moves

After the Great Depression wiped out savings and jobs, Washington rolled out a toolkit to stop the panic and put people back to work. Banks got a federal safety net so deposits wouldn’t vanish overnight (FDIC insurance), and risky Wall Street practices were fenced off (SEC policing markets; “Glass-Steagall” separating everyday banking from big bets). Millions of jobs came through public works—the WPA and CCC built roads, parks, schools, and trails; big regional projects like the TVA tamed floods and brought cheap electricity. Utility rules and the Rural Electrification Administration pushed power and phones to towns the market had skipped, with fairer rates.

All this required new, permanent agencies—the start of the modern administrative state: SSA (Social Security), NLRB (worker organizing rules), FHA (affordable mortgages), FCC (airwaves), and more. Day to day, that meant fewer bank runs, real paychecks from public jobs, lights on in rural homes, and a steadier floor under families (unemployment insurance, old-age benefits). The trade-off: a much bigger federal role and a maze of regulators—more stability and services, but also more rules and bureaucracy than before.

Upshot: Systemic risk tamed; decision-making shifts to Washington and regulated monopolies.

Skeptics: Localists, small bankers, some church leaders—worried about dependence and permanent centralization.

1913–1920s: The Federal Reserve & Income Tax

Before 1913, the U.S. had frequent bank panics and a patchwork of bank notes. Creating the Federal Reserve gave the country a central switchboard for money: one place that can rush cash to banks in a crunch (the “lender of last resort”), issue a uniform national currency, and nudge credit costs up or down to steady the economy. In the same year, the 16th Amendment launched a permanent federal income tax, replacing the old reliance on tariffs and one-off taxes. That gave Washington a steady paycheck, which helped fund big things (infrastructure, WWI finance, later New Deal programs) without waiting on customs revenue. Day to day, this meant fewer sudden bank runs and a more predictable money system—but also more centralized power over credit and a federal tax bill that comes every year.

Effect: Panic cycles moderated, but credit power now coordinated at the center.

Opposition: Sound-money agrarians, anti-trust populists—feared the “money trust.”

1870s–1910s: The Gilded Age Trusts

Pattern

Big “network” industries—railroads, oil, steel, telegraph/phone—got dramatically cheaper to run the bigger they got. Lay more track, run more barrels, pour more steel, and your cost per unit drops. That scale let the largest firms squeeze smaller rivals. To lock it in, tycoons used trusts and holding companies: they bought competitors or folded them into one umbrella so prices, routes, and supply could be set from the top. Think Standard Oil bundling refineries and pipelines, or powerful railroad pools fixing freight rates. Wall Street syndicates (bankers like J. P. Morgan) stitched together mergers, floated bonds and stocks, and stabilized prices—often by turning many firms into one giant. For the average town this meant cheaper mass-produced goods but less choice, higher freight charges for farmers and small shippers, and local businesses bullied by a few distant decision-makers. This is the era when “trust” became a dirty word—and why later we got antitrust laws to push power back down.

Local reality: Company towns; farmers hammered by freight rates and debt.

Pushback: Sherman/Clayton Acts, Granger movement, co-ops, municipal utilities.

1860s: Civil War, National Banking & Uniform Money

To finance the Civil War and tame a chaotic patchwork of bank notes, Congress passed the National Banking Acts. These laws created nationally chartered banks and a uniform U.S. currency, so a dollar in Ohio meant the same as a dollar in New York. Washington’s role grew as the federal government issued war debt, taxed more, and set tighter rules for banks—more stability, but more power centered in D.C. At the same time, the government showered railroads with land grants and loans to stitch the country together. That built a national market—farmers could ship grain to cities; stores could stock goods from far away—but it also sparked speculation and scandals and helped a few railroad barons control routes and prices. Everyday result: faster growth and wider choice, but higher leverage for big financiers and rail bosses, and less say for small towns and shippers who depended on a single line.

Losers: Independent state banks, local scrip; smallholders without political pull.

Winners: National financiers, trunk-line rail barons.

1830s–1850s: Jackson vs. the Second Bank; Localism with Panics

President Andrew Jackson shut down the Second Bank of the United States, the era’s central bank. He argued it concentrated too much power in elite hands. With it gone, federal money and deposits were spread to state-chartered “pet banks.” Credit became local and loose—easy loans, land speculation, fast growth—until the music stopped. Without a strong backstop, the system swung hard between booms and busts: the Panic of 1837 and later 1857 crushed many farms, shops, and frontier towns. Day to day, people liked the feeling of local control, but when confidence cracked there was no national safety net, so banks failed, savings vanished, and businesses folded. In short: more local say over money, but wilder cycles that hit ordinary folks the hardest.

Tension: Autonomy vs. stability. Local control returns—but volatility punishes the small.

1790s–1820s: Hamilton’s Blueprint & Early Corporations

After the Revolution, the new U.S. was broke and disorganized. Alexander Hamilton’s plan fixed the basics: the federal government took over the states’ war debts (“assumption”) so markets would trust the nation as a single borrower, and it set up the First Bank of the United States to act as a central hub for payments and credit. That gave America a reliable reputation—the government could borrow at better rates, and businesses could plan beyond the next harvest. At the same time, states began granting corporate charters with limited liability (owners weren’t personally wiped out if a venture failed). That made it safer to pool money for big projects like turnpikes and canals (think the Erie Canal), which became early transportation networks tying farms, towns, and ports together. Everyday effect: more stable money and credit, safer ways to invest, cheaper shipping, and wider markets—though critics worried this new finance-and-charter system favored well-connected investors over small farmers and artisans.

Debate: Hamilton’s national scale vs. Jefferson’s yeoman localism.

1776: Households, Guilds, and Mercantilist Shadows

Everyday economy

Local work, local goods

In 1776, most people made or bought what they needed close to home. Families farmed; nearby mills ground grain and sawed lumber; blacksmiths, cobblers, weavers, and carpenters handled tools, shoes, cloth, and houses. Town fairs and markets were the big shopping days. If something broke, you fixed it or took it to a local artisan—you didn’t order a replacement from far away.

Trade through imperial lanes

Overseas trade existed, but it flowed through the rules of empires. Under mercantilism, colonies sent raw stuff (timber, tobacco, furs, indigo) to the mother country and bought back finished goods (cloth, tools, chinaware). Governments handed out charters and special licenses to favored companies, which acted like early monopolies on certain routes or products. That meant some merchants had privileged access, while others were legally shut out.

Mixed money—coins, paper, and barter

There wasn’t one tidy money system. People used specie (gold and silver coins from various countries), colonial paper notes (“bills of credit”) issued by local governments, and lots of barter—paying in grain, rum, or labor when coins were scarce. Prices could vary from town to town, and debt often ran on tabs kept by the shopkeeper. It worked, but it was messy and uneven.

What everyday life felt like

Life was face-to-face and reputation-based. Your credit depended on your name in the community; your supplies depended on the harvest and the river. The upside: strong local ties, resilience through skills, and small-scale independence. The downside: limited variety, periodic shortages, slower growth, and rules tilted by imperial monopolies. The American Revolution didn’t just challenge a king; it also pushed back on this economic setup—seeking more open trade, clearer money, and room for local enterprise to scale.

Power map: Families, congregations, towns—thick local webs; thin national ones.

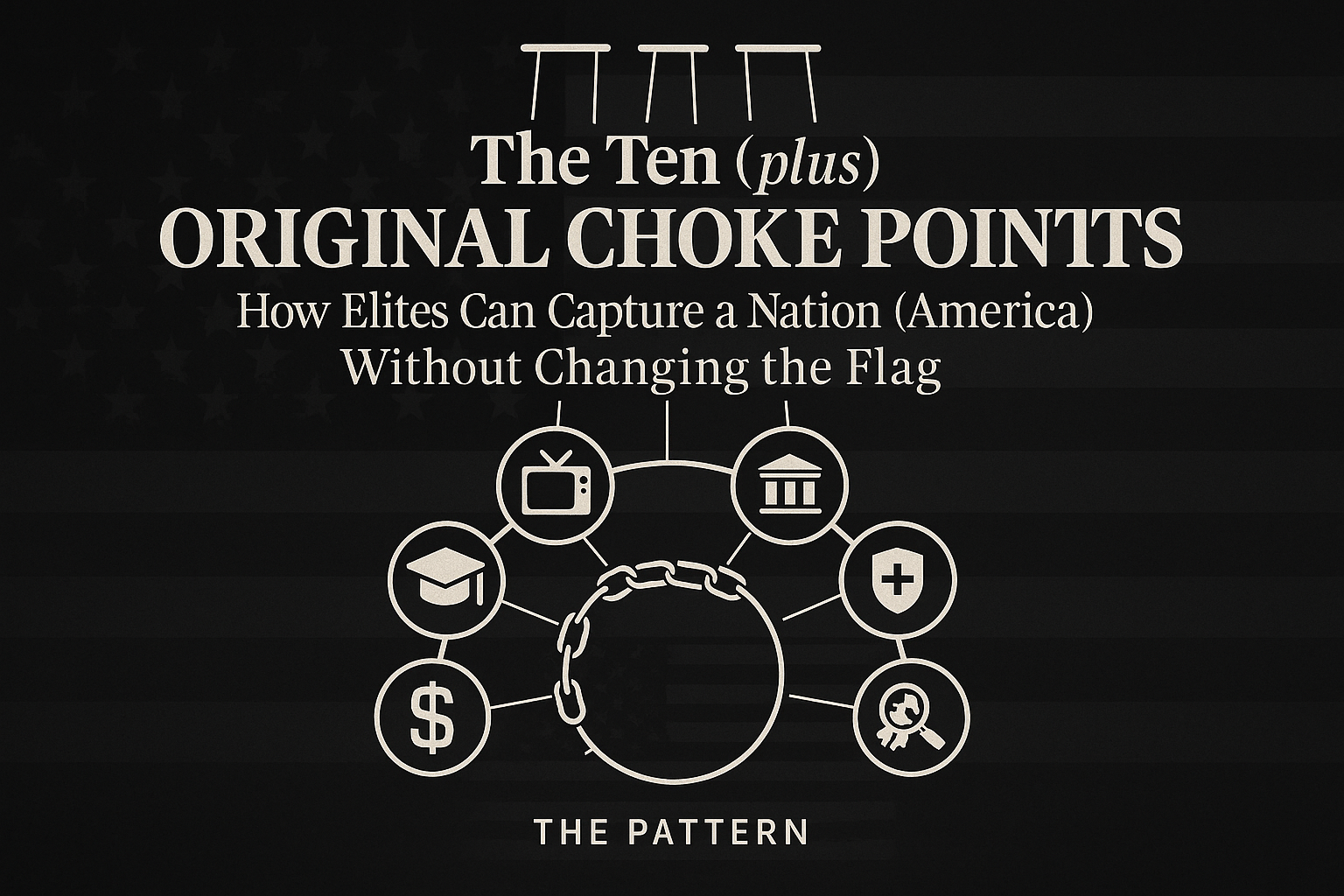

The Pattern (and why dissenters mattered)

Power moved up the ladder.

Every major “upgrade” promised efficiency or stability—but moved the real decisions farther from you. What used to be argued at town hall (you can show up, speak, and vote) shifted to the state capitol, then to federal agencies, then to global rule-setters and finally to private platform rule books (Terms of Service). Result: the rules that shape your work, speech, and business are often written by people you can’t easily face or replace. Example: a local council once decided which shops could open on Main Street; now a platform’s algorithm can decide whether your shop is even visible online—and you don’t get a microphone at that meeting.

Money turned into permissions.

We also moved from cash in hand (no gatekeeper) to bank credit (someone must approve), to securitized paper (your loan is chopped up and owned far away), to algorithmic permissions (an app or risk model says yes/no in real time). That’s efficient—until the switch flips. A bank can freeze a card; a payment network can block a category; a platform can auto-flag your account; an aid wallet can stop working outside a “geofence.” The more layers we add, the more your daily life depends on systems you don’t control—and the harder it is to fix a mistake because there’s no local banker or shopkeeper to talk to, just a help form and a bot.

Why dissenters mattered.

The people who pushed back weren’t anti-progress; they wanted progress with a steering wheel. They fought for public hearings, open standards, cash options, appeal rights, and competition—so efficiency wouldn’t become unaccountable control. When they won, you felt it as small but real freedoms: the ability to switch providers, to use cash when the app fails, to appeal a bad algorithmic decision, and to see (and challenge) the rules that govern your life.

People who stood up—co-op founders, antitrust crusaders, local bankers, labor leaders, privacy and open-standards advocates—weren’t anti-progress. They were the brakes that kept “efficiency” from becoming extraction.

A Reverse-Engineering Map (today → 1776)

Today’s control stack

- Money & credit: Central banks, primary dealers, global dollar plumbing.

- Networks: Platforms, app stores, clouds, payment rails.

- Law & policy: Federal preemption, administrative rules, global standards.

- Ownership: Index funds & PE firms holding slices of everything.

1776’s control stack

- Money: Local notes, specie; community credit.

- Networks: Roads, rivers, local markets; few monopolies.

- Law: Town and state primacy; lean federal core.

- Ownership: Family farms/shops; guilds; mutuals; co-ops.

Net effect: We traded resilience + voice for scale + speed—and the bill is concentration.

How to Rebalance Without Burning the House Down

Monetary & financial

- Level the rails: real-time payments open to credit unions/community banks; cap junk fees.

- Diversity of money: preserve cash; support open, interoperable digital payments (no single gatekeeper).

- Anti-bailout design: credible resolution for “too big to fail,” higher loss-absorbing capital, living wills that actually work.

Markets & platforms

- Interoperability mandates: app stores, social graphs, and payment APIs must open on fair terms.

- Structural antitrust: where conduct remedies fail, separate core platforms from lines of business.

Ownership & place

- Rebuild local balance sheet: employee ownership (ESOPs), co-ops, community land trusts, public-interest trusts for utilities.

- Keep rents local: revenue-sharing from natural monopolies (rights-of-way, spectrum) to cities and counties.

Law & process

- Sunset & audit: emergency powers auto-expire; surveillance and subsidies require periodic public re-approval.

- Due-process by design: human appeals for automated blocks; publish takedown stats and error rates.

Civic muscle

- Memory over propaganda: public ledgers of subsidies, contracts, mergers; teach the fights that built the system.

- No jersey exceptions: standards apply regardless of party or logo.

A Simple Test (use it anywhere)

- Distance: Did this change move decisions farther from the people affected?

- Exit: Can a town, firm, or user leave without losing basic livelihood?

- Share: Do locals get a clear cut of the value created (and a say), or just the risks?

- Sunset: Are there end dates and audits—or does “temporary” become forever?

If the answers point to farther, no, no, and never, you’re watching another turn of the concentration ratchet. The people who push back aren’t anti-progress—they’re the ones keeping the commanding heights from becoming a private mountain range.

Reverse-engineering our economy shows a long migration of power—from households and towns to platforms and central desks. Each step brought real gains, but also fragility and dependence. We don’t need nostalgia for 1776; we need plural, accountable, human-scaled systems that borrow the best of scale without erasing local voice. The fix isn’t a revolution; it’s many small repatriations of power—money, markets, and decision rights—back to the people who live with the outcomes.