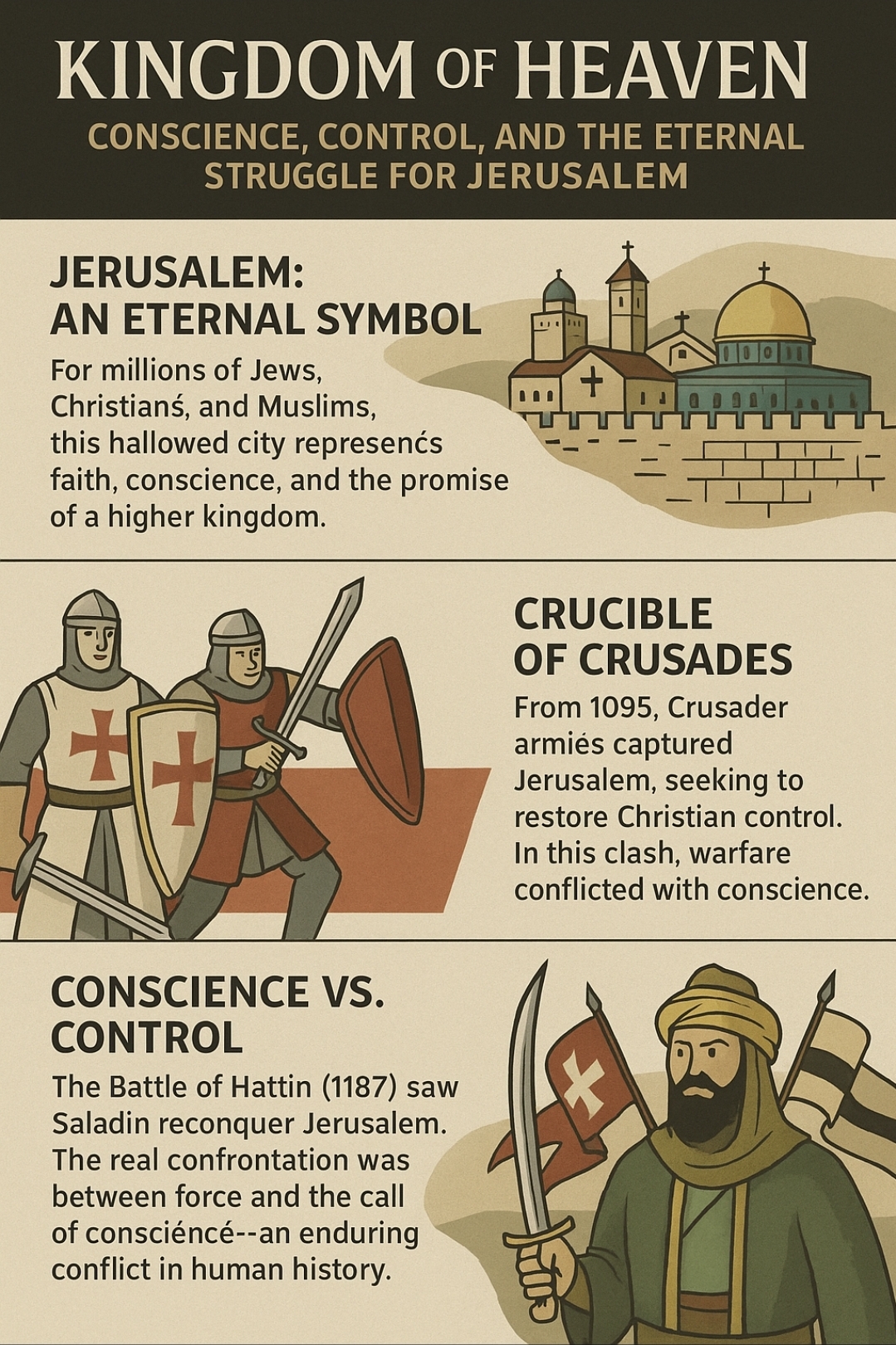

When Ridley Scott released Kingdom of Heaven in 2005, critics treated it as a medieval war epic. Yet beneath the armor, catapults, and desert vistas, the film whispers truths that echo across centuries. Its story is not just about Jerusalem in 1187—it is about conscience versus fanaticism, truth versus propaganda, and the eternal question of whether humanity will awaken before institutions collapse under their own corruption.

The Moral Frame: Courage Beyond the Tribe

At its heart, the film is about one man’s moral evolution. Balian, a grieving blacksmith, journeys to Jerusalem and finds himself defending not just a city but the very idea of conscience. Where the Crusader lords cry “God wills it” as a justification for conquest, Balian protects civilians—even surrendering the city peacefully to Saladin when resistance would mean slaughter.

This moral choice places him in Kohlberg’s highest stages of development: conscience over conformity, universal principles above tribal loyalty. The leper King Baldwin IV embodies the same spirit—physically broken, yet morally strong, seeking peace rather than vengeance. In contrast, Guy de Lusignan and Reynald de Châtillon represent the corruption of Stage 4 legalism: obedience to “law” twisted into blind cruelty.

The lesson: true freedom is moral freedom. Conscience, not the sword, defines the kingdom of heaven.

Conscience vs. Tribe: The Real Battle in Kingdom of Heaven

The heart of the movie isn’t just swords or kings — it’s the battle inside the human soul.

- Guy de Lusignan and Reynald de Châtillon live by fear and tribe. Their “morality” is shallow: obey orders, protect our side, crush the enemy. They twist law into cruelty. Their loyalty isn’t to God, but to power.

- Baldwin IV, the Leper King, shows the opposite. Broken in body, but strong in spirit, he seeks peace because he knows the higher law: protect human life, even when war seems easier.

- Balian follows that same path of conscience. He refuses to hate simply because his “tribe” demands it. He fights for justice, not vengeance, even when it costs him power, prestige, and safety.

Three Kinds of Morality Made Simple

Fear-Driven: “Do what you’re told, or else.”

– Obey orders, avoid punishment.

Tribal Loyalty: “My side is always right.”

– Blind obedience to group, law, or leader.

Conscience: “Do what’s right, even if my side hates me for it.”

– Higher principles of justice, life, and truth.

The film shows us this choice in flesh and blood. Guy and Reynald prove how fear and tribe lead to destruction. Baldwin and Balian remind us that conscience is the only path that protects both dignity and peace.

The Geopolitical Frame: Land as Power

Jerusalem in the 12th century was both sacred and strategic. Whoever controlled it controlled pilgrimage routes, trade arteries, and legitimacy in the eyes of nations. Saladin’s campaigns were not only about faith but about sovereignty.

The film reveals how religion cloaks material ambition—a lesson as relevant now as it was then. Wars sold as “holy” are often about wealth, land, and power. Just as medieval Crusaders invoked God to seize territory, modern states invoke “democracy” or “security” to secure oil fields, trade routes, or geopolitical footholds.

The lesson: geopolitics is rarely about what it claims. Look beyond the banners to see the banks and resources beneath.

The Cultural Frame: Belief-System Prisons

Religion in the film functions as both a source of faith and a cage of obedience. “God wills it” becomes a medieval slogan no different from modern mantras like “Support the troops” or “Follow the science.” It silences questioning, transforms war into virtue, and binds people into tribal prisons.

Christians reflexively defend Jerusalem; Muslims reflexively fight for it. But in the struggle, ordinary Jews, Muslims, and Christians all suffer while elites enrich themselves. The cultural mechanism is timeless: division keeps people fighting each other instead of noticing the common enemy—the system of control.

The lesson: cultural programming manufactures obedience. Conscience is the only jailbreak.

The Institutional Frame: Gatekeepers in Crisis

Institutions in Kingdom of Heaven are exposed as brittle. The Church promises protection but flees at the first sign of danger. Nobility promises order but pursues vanity. Even the knighthood oath—“to defend the helpless”—is betrayed by knights who defend their own status instead.

This mirrors the failures of modern institutions: schools that indoctrinate rather than educate, governments that legislate for the powerful rather than the people, churches that barter truth for influence. When the walls of Jerusalem fall, the people discover the truth: their survival lies not in institutions but in community, courage, and principle.

The lesson: when institutions rot, conscience and community must rise.

The Prophetic Frame: End Times, Then and Now

The fall of Jerusalem in 1187 carries apocalyptic overtones. For Crusaders, it was the end of an age. For Muslims, it was divine vindication. The echoes are prophetic: land and power rise and fall, but conscience endures.

Saladin’s famous reply to the question of what Jerusalem is worth—“Nothing… everything”—captures the paradox of prophecy. Earthly kingdoms are both insignificant in eternity and yet central to the trial of human conscience.

The lesson: prophecy is less about predicting meteors and more about exposing choices. Jerusalem is a stage where humanity reveals whether it will bow to fear and ambition or rise to truth and conscience.

Bridging Film and Reality

Historically, the film takes liberties—softening Saladin’s brutality, idealizing Balian, and simplifying Crusader politics. Yet its essence is true: the Crusades were not noble pilgrimages but geopolitical wars cloaked in religion. The same pattern continues today.

Kingdom of Heaven thus becomes more than cinema. It is a teaching tool. It shows how:

- Morality can resist tribal hatred.

- Geopolitics disguises greed as virtue.

- Culture traps people in belief prisons.

- Institutions fail when virtue dies.

- Prophecy warns that every age faces the same test.

The Takeaway: Building a Kingdom of Conscience

The film closes with Balian returning to his forge, refusing a throne but holding his integrity. That is the prophetic model: the remnant who live awake, who serve conscience above empire, who defend the helpless without craving the applause of kings.

Kingdom of Heaven is not just about medieval Jerusalem. It is about every city, every nation, every age. The walls may change, the slogans may change, but the struggle is the same: will we build kingdoms of conquest—or a kingdom of conscience?