Thomas Jefferson feared not cities as places, but concentration as a habit of rule. Pack enough people, money, and decision-rights into a few nodes and the old republican arts—local consent, civic responsibility, the everyday practice of self-government—atrophy. What he wanted most for the American experiment was not pastoral nostalgia but dispersed authority: many centers of power, close to the governed, constantly checking and educating one another.

He said it in different keys. In his paeans to the yeoman he praised independence of livelihood because it underwrote independence of mind. In schemes for “ward republics” he tried to miniaturize the republic into units small enough for every person to see and touch: a school, a constable, a jury, a road crew, a militia company—governance you could meet on Tuesday night. Even his famous push for public education was not primarily a national project; it was a local one meant to cultivate citizens capable of judging those who would govern them. Running through it all was a simple instinct: liberty dilutes when power aggregates.

“No, my friend, the way to have good and safe government is not to trust it all to one, but to divide it among the many, distributing to every one exactly the function he is competent to.

Let the National Government be entrusted with the defence of the nation and its foreign and federal relations; the State governments with the civil rights, laws, police and admisnistration of what concerns the State generally; the counties withe local concerns of the counties, and each ward direct the interests within itself.

It is by dividing and subdividing these republics from the great national one down through all its subordinations, until it ends in the administration of every man’s farm by himself; by placing under every one what his own eye may superintended, that all will be done for the best.” – Thomas Jefferson (Letter to Josephs C. Cabell Letters, p.1388. 1816)

Concentration, after all, does several corrosive things at once.

First, it professionalizes politics into a spectator sport. When distance—geographic and institutional—opens between decision makers and citizens, participation migrates from doing to “liking,” from committees to comment boxes. A handful of party operatives, donors, pollsters, and consultants come to mediate the public’s will. The ordinary citizen becomes a data point in someone else’s dashboard, not a co-author of local rules.

Second, concentration homogenizes rule. A few urban hubs set policy templates that are then exported—often by statute, sometimes by subsidy—into places with different economies, geographies, and civic traditions. State preemption of local ordinances, one-size labor and land-use mandates, and federal grant strings can all have this effect. The result is not thoughtful equality under law but a sameness that ignores local knowledge.

Third, concentration invites dependency. When essential services—energy grids, broadband, payments, news, public health capacity—are controlled by a small number of parties, failure or capture spreads system-wide. It takes only a few regulatory chokepoints or platform policy shifts to change the terms of ordinary life. Citizens become petitioners. Towns become price takers. Elected officials become brokers for favors rather than stewards of shared assets.

Finally, concentration hides responsibility. When power is stacked in layers—state authority trumping local, national trumping state, platform policy trumping all—who do you hold accountable for a school boundary, a water rate, a zoning map, a news blackout? “It’s complicated” becomes a shield for “it’s no one’s fault.”

You don’t have to romanticize the 18th-century countryside to see Jefferson’s worry confirmed by today’s mega-metropolitan reality. A handful of regions now dominate capital formation, media production, and political fundraising. Party machines are nationalized brand managers more than neighborhood coalitions. “Platform bureaucracies”—companies that set de facto rules for speech, commerce, and association—govern large zones of civic life with terms-of-service instead of due process. These concentrations don’t merely reflect economic gravity; they shape it, bending policy back toward central rule.

The remedy isn’t an anti-urban crusade; cities concentrate because specialization and proximity create genuine prosperity and culture. The remedy is constitutional housekeeping that keeps scale from becoming sovereignty. In other words: recommit to republican pluralism—many centers of initiative, each with real powers and real duties.

What might that look like in practice?

1) Bring decisions back where people can see them

Make everyday rules truly local

Some choices are about your street, your kid’s school, your corner store. Those shouldn’t be set by distant offices.

- Land use: Your town decides where duplexes, shops, or parks go—not the state. If there’s a real regional issue (like air quality or a shared river), then the state steps in.

- Street design: Neighbors help decide speed limits, crosswalks, bike lanes, and where to put trees or lights.

- School setup: Families and teachers shape school hours, programs, and how to handle homework and discipline.

- Small business rules: Let locals set things like signage, outdoor seating, and food-truck spots.

If the state does override locals for a true spillover (say, a highway or a watershed plan), it should still let cities raise and spend enough of their own money to meet local needs their own way.

Shrink government units so people know each other (Ward-scale governance)

Big bureaucracies treat everyone the same. Small ones can use names, not numbers.

- Schools: Each school has a council of parents, teachers, and neighbors that can hire the principal, choose curriculum options, and set real policies—not just “advise.”

- Public safety: Neighborhoods can sign policing contracts that spell out patrol style, response times, and priorities (e.g., traffic calming vs. property crime), with monthly public scorecards.

- Budgets: Do participatory budgeting at the block or ward level. Give residents a pot of money and let them vote on concrete projects—fix a crosswalk, add shade at the playground, fund a teen job program.

What this looks like on the ground

- Your street votes to add a speed hump and a 4-way stop; the city installs it within the year.

- Your school’s council hires a principal who keeps recess, adds an apprenticeship program, and pilots phonics because parents asked.

- Your ward’s budget night ends with funded projects you’ll see in six months, not a wish list no one ever builds.

Bottom line: If a rule mainly affects your neighborhood, your neighborhood should write it. Keep the big, regional stuff big—and let everything else live close to the people who live with it.

2) Spread out money power so it can’t buy political power

Update the rules for middlemen (the giant platforms)

The issue: A few companies now sit between us and everything—news, customers, payments, even search. When they control the gate, they tilt the game.

The fix in simple terms:

- Make them play nice together: Your data and contacts should move with you. If you switch apps, your stuff comes along (like keeping your phone number when you change carriers).

- Treat core services like utilities: For basic functions—finding, speaking, paying—big platforms should carry everyone on fair terms, not pick winners.

- Stop buy-outs that snuff out local upstarts: Don’t let giants buy tomorrow’s competition before it grows.

Everyday impact: Your neighborhood bakery doesn’t live or die by one app’s fees. You can reach customers across platforms without starting from zero.

Fund local muscle, not local begging

The issue: Towns chase distant grants with strings attached, wasting time on paperwork and buzzwords.

The fix in simple terms:

- Send money by formula, not contest: Give each place a clear slice for broadband, pipes, housing, micro-grids.

- “Use it or lose it” capital budgets: If a city doesn’t build, the funds roll to the next town that will.

Everyday impact: Fiber gets laid on your street because your city can plan and hire, not because it won a trendy grant.

3) Make parties and politics feel neighborly again

Revive the Caucus System: Choose Leaders Face-to-Face

The issue: Modern primaries reward volume over virtue. Small, closed contests are dominated by the loudest fringe and the best-funded candidates. Voters are reduced to spectators in a media war rather than participants in deliberation.

The fix: Return to a caucus-style system where citizens gather in person, debate, and decide together. Caucuses favor informed discussion, community accountability, and character over slogans.

Everyday impact: You get representatives who are locally rooted, known to their neighbors, and answerable to real people—not just to donors, algorithms, or national outrage cycles.

Rebuild local news and real discussion

The issue: No local reporters = rumors and national outrage-farming.

The fix in simple terms:

- Seed community news co-ops; tax credits for local reporters.

- Public forums that mix experts with citizen juries (regular folks who hear both sides, then recommend).

Everyday impact: You learn what your school board did last night, not what a stranger screamed on the internet.

4) Use “do it closest to home” inside government

Set goals at the top; solve them at the bottom

The issue: One-size rules don’t fit the whole map.

The fix in simple terms:

- Higher levels set the floor (“air must be this clean”).

- Towns pick how to meet it, try different methods, measure in public, copy what works. (This is Ostrom’s “many centers” idea.)

Everyday impact: Your county tackles stormwater with rain gardens; the next one uses ponds—both hit the target.

Keep laws narrow, temporary, and visible

The issue: Jumbo bills hide who did what; powers never end.

The fix in simple terms:

- Single-subject bills (one topic at a time).

- Sunset dates on big delegations—make Congress/statehouses renew them.

- Plain-English local impact notes: What this law means on your block, in dollars and steps.

Everyday impact: You can actually track decisions and hold the right person accountable.

5) Put citizenship back at the center of school

The issue: We graduate test-takers, not self-governing neighbors.

The fix in simple terms:

- Civic apprenticeship all the way through school:

- Students sit on real boards (budget committees, park councils).

- They maintain shared spaces (trails, gardens) with a budget and a deadline.

- They run school enterprises (print shop, café, tech help desk).

- They testify at city meetings after doing the homework.

Everyday impact: By 18, a kid has proposed a bylaw, balanced a budget, and delivered on a project—muscle memory for self-rule.

The big caveat (and how to aim true)

Some problems are bigger than a county: rivers, power grids, finance, war. Those need coordination. Jefferson used national tools when they protected liberty (Louisiana Purchase secured a continental common). The point isn’t “small for small’s sake.” It’s fit: match the size of the rule to the size of the problem—and keep the rest close enough for us to see, argue, and amend.

Why this matters: Tocqueville admired the New England town because people learned to govern by governing. You can’t stream that skill from a capital or outsource it to a platform trust-and-safety team. You build it where you live—on the block, in the parish, at the school, in the watershed.

End state: When decisions live near us, we grow citizens who are hard to buy, hard to scare, and hard to ignore. That’s Jefferson’s real warning flipped into a plan: don’t just fear concentration—dilute it. Turn neighbors into governors. Make politics a workshop, not a stadium. Keep liberty thick at the edges, where life actually happens.

What Jefferson actually feared (and why)

1) Dense agglomerations corrode civic virtue

Jefferson worried less about skylines than about the social physics of crowding: when people are stacked “one upon another,” anonymity rises, production detaches from responsibility, and a few organizers can mobilize many. In small settings you must look your neighbor in the eye; in great cities, intermediaries (bosses, brokers, fixers, party machines) step in. That distance blunts the habits a republic needs—mutual accountability, thrift, voluntary association, and the pride that comes from visible workmanship.

Design implication: keep crucial civic functions close to face-to-face life—schools, juries, militia (today: emergency response and civil defense), street governance, markets—so the link between choice and consequence stays intact.

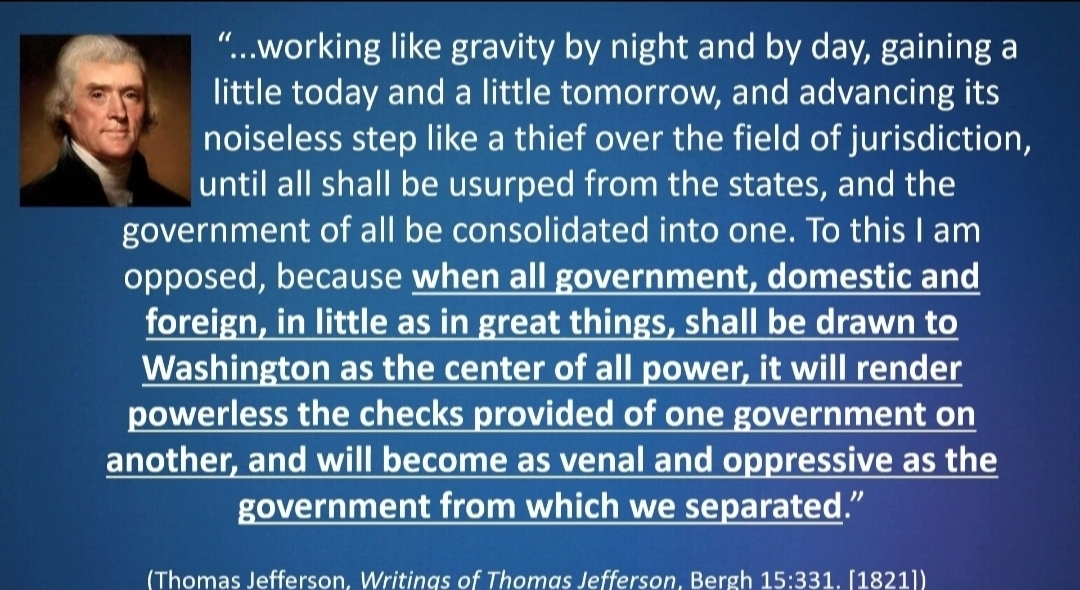

2) Republican control thins with distance and scale

For Jefferson, “republican” meant citizens can actually steer rulers. As the decision center moves farther away, two things happen:

- Information about local conditions degrades. One statute or program misses many climates, economies, and traditions.

- Responsibility blurs. When layered authorities overlap, every officer can say “not my department.”

Design implication: match authority to the smallest competent scale. Let higher levels do true common goods (defense, interstate trade, rivers, air) and leave the rest to counties, towns, wards, associations, and households. When a higher level does act, it should set outcomes but let local actors choose the means.

3) Divide power to preserve freedom

Jefferson’s famous “ward republics” were not pastoral daydreams; they were governance architecture. He wanted each person to belong to a unit small enough to meet in person and handle real tasks: roads, schools, police watch, poor relief, juries, elections. That cellular structure forces practice in self-rule and keeps larger bodies from absorbing everything.

Design implication: build many centers of initiative—state → county → town → ward → voluntary corps → family → person—and make sure each tier holds real tools (revenue, hiring, contracting, vetoes), not just “advisory” status.

How centralization works now

1) Urban blocs + donor corridors = statewide steering

- Dense coalitions win primaries. In winner-take-all systems, a few metro counties can decide statewide races. Candidates optimize for those precincts’ preferences, not the state’s median voter.

- Money moves on the intercity rails. Major donors, foundations, and lobbying firms cluster in a handful of metros. Their bundled giving sets agendas, supplies staff, and writes model bills.

- Media reach is asymmetric. State capitals increasingly rely on metro newsrooms and national outlets; local papers shrink. Narratives (and outrage cycles) are set where cameras live.

Practical effect: budgets, siting decisions, and rulemaking tilt toward where votes, money, and coverage concentrate—often far from the communities bearing the consequences.

2) Administrative consolidation makes “one size” the default

- Regional authorities and compacts. Transportation, water, housing, and air boards pool jurisdiction and debt. Useful for spillovers; also a way to move big policy out of town-hall reach.

- Mandates + metrics. State and federal statutes tie funds to compliance dashboards. Local discretion narrows to “check the box or lose the grant.”

- Grant strings. Competitive grants nudge policy harmonization (curriculum frameworks, land-use targets, policing standards). The form design pre-bakes the outcome.

Practical effect: uniformity beats fit. Localities become implementers of distant designs, adapting their reality to the spreadsheet rather than the other way around.

3) Platform governance runs daily life by Terms of Service

- Identity: Single sign-on, credit bureaus, device IDs, and app-store accounts gate access to work, services, and speech. Suspension becomes civil death in miniature.

- Payments: Card networks, app stores, ad exchanges, and a few processors determine which causes, vendors, or newsrooms can be funded. Risk teams become de facto policy boards.

- Speech & reach: A handful of feeds, search indexes, and moderation stacks decide what is seen, when, and by whom; appeal paths are slow or opaque.

- Policy by API. “Compliance” ships as code. If a platform updates rules, everyone downstream must conform overnight or be throttled.

Practical effect: crucial freedoms (association, expression, livelihood) hinge on private rulebooks written far away, with minimal due process and few local escape hatches.

4) Crisis rule becomes the habit

- Emergency declarations stretch. Health, climate, cyber, grid—new categories keep the extraordinary ordinary.

- Directive over deliberation. Agencies and executives act first via orders and guidance; legislatures ratify later, if at all.

- Ratcheting asymmetry. Temporary rules expire on paper, but agencies retain the tooling, data collection, and precedents; they can be switched on again quickly.

Practical effect: civic muscle atrophies. Citizens learn that decisions appear from above, justified by dashboards they didn’t build and can’t interrogate.

Net effect: politics happens to people, not through them

When outcomes feel pre-cooked elsewhere, participation shifts from co-creation to performance: petition, protest, post, repeat. Trust erodes; turnout narrows to the intensely motivated; policy whiplash grows as each election aims to capture the distant center rather than solve shared problems at human scale.

Why this structure is sticky

- Economies of scale: It’s cheaper (for central actors) to standardize procurement, data schemas, and compliance.

- Liability + reputational risk: Central rulemakers prefer uniform rules to avoid blame for variance.

- Network effects: The more people a platform or program enrolls, the harder it is to exit without social or economic penalty.

- Staff pipelines: Talent circulates among a few metros, agencies, firms, and think tanks—reproducing the same playbook.

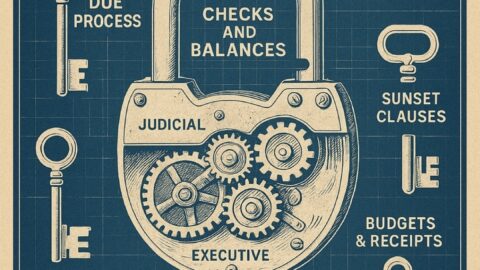

What keeps centralization honest (if we choose to use it)

- Subsidiarity with enforcement: Presume local control unless a real spillover is proven; require higher authorities to publish the externality and the least-intrusive remedy.

- Outcome floors, method freedom: Set state/federal results (e.g., water quality, graduation competence) but let counties/wards choose the means.

- Sunset + reauthorization: Emergency powers, guidance documents, and pilot programs auto-expire without an affirmative vote and public impact review.

- Open rails: Interoperability, data portability, and due-process standards for dominant platforms; neutral access for payments and app distribution.

- Participatory budgets at ward scale: Give neighborhoods line-item control over a slice of capital and operations (streets, safety, parks) with transparent ledgers.

- Grant redesign: Convert compliance-heavy competitive grants into formula dollars with broad guardrails; publish “strings” in plain language with opt-out pathways.

- Local evidence loops: Require agencies to A/B test policies across willing localities and publish effects; reward divergence that works.

- Media federalism: Incentivize local reporting (legal ads, FOIA fee waivers, open meeting streams), so agenda-setting isn’t wholly metro-centric.

A citizen checklist (what you can do where you live)

- Join or start a ward council; push for a binding share of the budget.

- Ask your city/county to adopt a “spillover test” before it cedes control upward—or preempts downward.

- When agencies cite “best practices,” demand the evidence and the variance: where did it fail and why?

- Support local news with subscriptions and tip-lines; insist on beat reporting for boards and authorities.

- Prefer tools and vendors that offer export, federation, and appeals; treat closed platforms as a last resort for core civic functions.

Centralization isn’t villainy by definition; it’s a geometry. Use it for rivers, and grids; resist it for schools, streets, and speech. Keep authority as close as competence allows, and politics becomes something you do, not something done to you.

Today’s confirmations of the worry

- Mega-metros and machine politics: fundraising, media, and administrative leverage concentrate in a few hubs; state and federal policy begins to mirror the needs and outlooks of those hubs.

- Platform bureaucracies: private rulemakers set de facto speech, trade, and association rules for everyone via terms of service, with few local escape hatches.

- Grant-state centralism: money flows with strings; localities chase compliance over fit, trading discretion for dollars.

Jeffersonian remedies

- Subsidiarity with teeth

- Presume home rule for land use, schools, public safety, and small-business regulation.

- Use state preemption only for real spillovers (watersheds, air basins, regional transit). Pair any preemption with local revenue authority.

- Ward-scale governance

- Break counties into neighborhood jurisdictions with budgets and duties ordinary citizens can shoulder. Neighborhood councils control line items (traffic calming, parks, street lighting) via participatory budgeting.

- Polycentric administration

- For shared problems (rivers, grids, epidemics): set outcome floors centrally; let counties and compacts experiment with means; publish results.

- Antitrust and interoperability for civic chokepoints

- Treat dominant platforms’ core functions as common carriage (neutral access, due process).

- Mandate data portability and open protocols so communities can choose alternative providers without civic amputation.

- Re-civicize schooling

- Embed service, deliberation, and enterprise: student-run courts and newsrooms, junior fire/EMS auxiliaries, local history and budgeting labs, real internships tied to public work.

- Clear lines of accountability

- Single-subject legislation, sunset clauses for large delegations, and plain-language local impact statements (“who decided, with what authority, by what evidence”).

- Juries and militias

- Civic obligations that train judgment and bind defense to the defended.

- Public education (local, not national)

- Schools to form citizens—literate, numerate, historically aware—run near home, not by distant ministries.

- Give school communities real say over hiring, schedule, and curriculum within broad standards.

- The University of Virginia’s form

- No chapel, little pomp, a village of pavilions—an academic commonwealth designed for inquiry, not hierarchy

The principle beneath the program

Jefferson’s point wasn’t “farms good, cities bad.” It was: government must fit the human scale. Where law is near, people can argue, amend, and own it; where law is far, they adjust or disengage. A durable republic therefore prefers many small sovereignties, loosely joined, over one tall pyramid with kind intentions.

Keep decisions within sight of the people they bind, and you get citizens who are hard to buy, hard to scare, and hard to ignore. Let power stack up in a few nodes, and you get subjects with good streaming options. The choice remains ours.

Then vs. Now: The Same Logic, New Tools

| Jefferson’s Principle | 21st-Century Expression | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Keep authority local | Preemption laws, grant conditions, national standards | Towns become implementers, not deciders |

| Beware factions in dense centers | Party machines + NGO/think-tank ecosystems | Narrow consensus, little dissent inside the “blob” |

| Tie rules to responsibility | Administrative rulemaking by distant agencies | Accountability blurs; no one “owns” bad outcomes |

| Small units preserve virtue | Mega-metro governance & regional compacts | Rural and small-city voices sidelined |

Why It Matters

When decisions move up and inward, three things follow:

- Moral distance: Rule-makers don’t live with the consequences.

- Path dependence: Central systems, once installed, are hard to unwind.

- Civic atrophy: Citizens stop practicing self-government because there’s nothing meaningful to govern.

A republic doesn’t die in a single vote; it atrophies as people conclude participation doesn’t matter.

A Jeffersonian Recovery Plan

These aren’t partisan fixes—they’re scale fixes.

- Reverse the flow of authority

- Sunset statewide mandates that preempt competent local control.

- Require statutory (not just administrative) authority for any rule binding counties and towns.

- Budget where we live

- Push percent-of-budget to local thresholds (e.g., 50% of education and public safety dollars decided locally).

- Tie grants to outcomes chosen by communities, not line-item compliance.

- Rebuild civic venues

- Charter citizens’ assemblies and school-district juries with binding recommendations.

- Restore town-meeting powers: zoning, procurement, and oversight within the community.

- Make agencies face the governed

- Put rulemaking on the road: regional hearings with recorded, line-by-line responses—to be published before rules take effect.

- Automatic review-and-expire clocks on emergency orders and major rules unless re-authorized after local hearings.

- Open the platforms we depend on

- Treat dominant digital rails (ID, payments, core speech carriage) as common carriers with neutrality, due process, and portability—so local life isn’t hostage to distant moderators.

- Elect by smaller maps

- Expand districts or use multi-member local districts with proportional methods so urban majorities don’t erase regional minorities.

How Citizens Can Start (This Month)

- Map the mandates: List the top five state/federal rules constraining your council or school board; demand sunset/review dates.

- Local budgets 101: Host a public “follow the dollar” night—what’s decided here vs. elsewhere? Push to move decisions home.

- Hearing discipline: Refuse rubber-stamp hearings. Ask for written responses and implementation timelines. Publish them.

- Build coalitions across town lines: Small cities and rural counties together can match metro clout when they coordinate.

Conclusion: Keep the Republic—At Human Scale

Jefferson’s message isn’t anti-city; it’s pro-scale. A free people must keep power where responsibility lives. When decisions stack in distant centers—political, bureaucratic, or corporate—the republic thins into a managed state. Reversing that arc means returning authority to neighbors, not to parties; to charters and juries, not to dashboards; to people who must live with what they decide.

That’s not nostalgia. That’s the operating manual for a republic.