If you only knew Mr. Robot as “that hacker show,” you missed why it hit a nerve. USA Network built it for younger adults—especially millennials—who live online, speak privacy and platforms fluently, and are suspicious of systems that feel rigged. Ratings never chased mass sitcom numbers, but the 18–49 core was sticky, the fandom obsessive, and the conversation outsized: coders, creatives, policy wonks, and conspiracy debunkers argued side-by-side about what the show said—and what it warned.

Politically, the audience was eclectic but not apolitical. The series wears an anti-corporate, anti-surveillance ethos on its sleeve: debt traps, captured regulators, data brokers, and the “stack” that sits between people and power. That drew progressives who bristle at corporate overreach—and libertarian-leaning privacy hawks who distrust state backdoors. In other words, it wasn’t red vs. blue; it was center stage vs. backstage: who really runs the rails, and how would we know?

This is where Hollywood mirrors real life. Mr. Robot arrived alongside news cycles about ransomware, data breaches, algorithmic nudging, and the slow privatization of public space via “terms of service.” The show exaggerates for drama—bombs, secret orders—but the mechanisms are ripped from white papers and incident reports: honeypots and femtocells, supply-chain trust, title records and “single sources of truth.” It’s fiction as a lab, running worst-case simulations of what can happen when convenience beats governance and we outsource memory to databases we don’t audit.

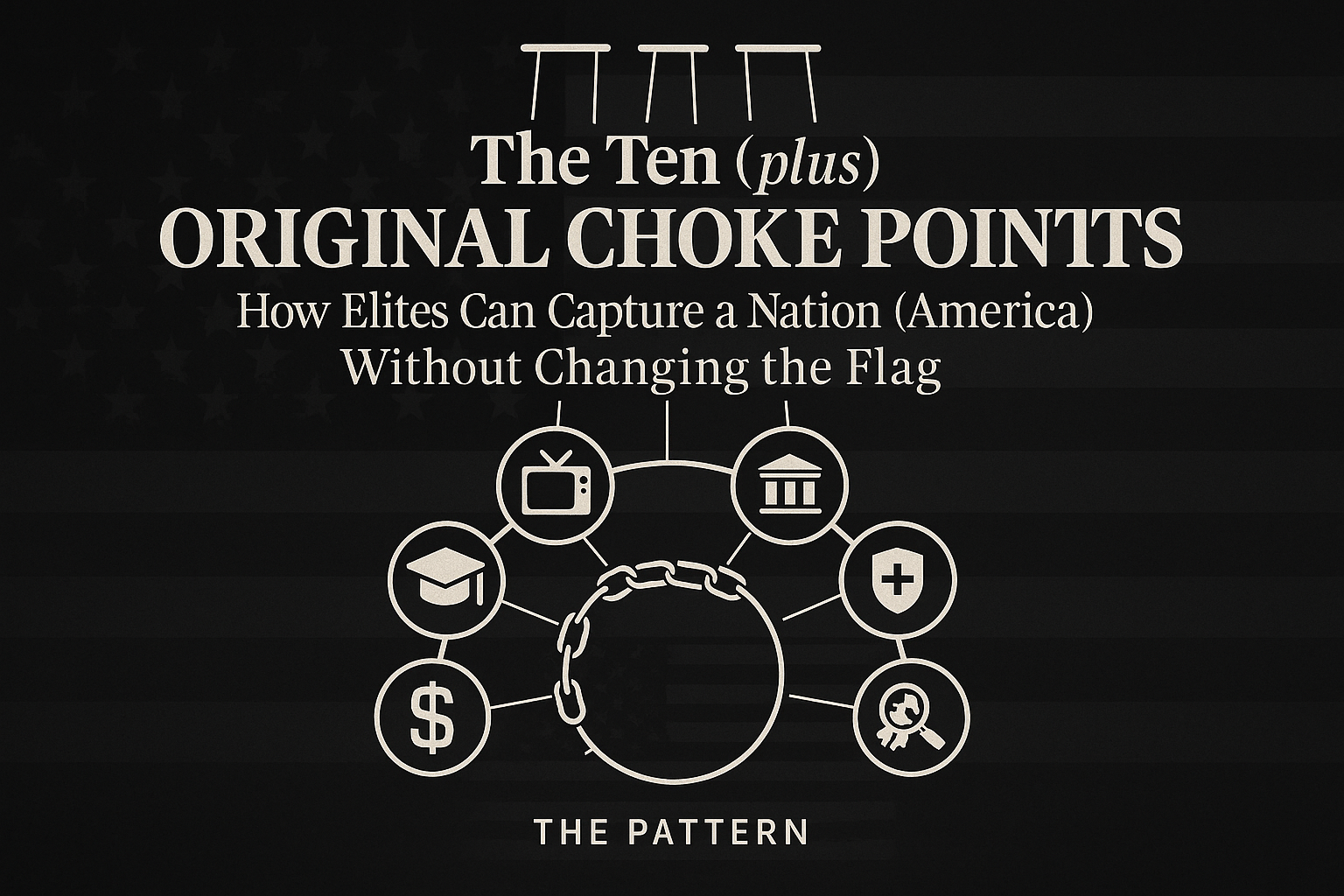

Why watch it now? Because it’s a decoder ring for the world we’re sliding into. The series doesn’t just thrill; it teaches you to spot control points: identity, payments, platforms, property records, and the narratives that legitimize them. It models how power edits reality—PR talking points, compromised investigators, and “emergency” rules that never sunset—and how fragile systems become when we centralize the ledger and remove sunlight.

Understanding Mr. Robot isn’t about catching every twist; it’s about learning the habits it rewards: follow the incentives, map the chokepoints, log the changes, demand transparency, and keep redundant proofs of what matters (from your files to your rights). If you do that, the show stops being just entertainment and becomes what the best pop culture can be: a rehearsal for real life.

The uncomfortable mirror the show holds up: even anti-system art can function like propaganda. A series that teaches you to distrust “the stack” can also manufacture trust in a new stack of ideas and heroes. The craft is so good—sound design, soliloquies, plausible hacks—that the aesthetic of realism becomes a persuasion engine. When the vibe feels true, many viewers import the worldview wholesale. That’s not a moral failure; it’s how narrative works.

Notice how the show’s issue agenda quietly steers attention: debt traps, dark money, surveillance capitalism, captured regulators. Agenda-setting theory says media doesn’t tell you what to think, it tells you what to think about. The more screen time those topics get, the more salient they become for the audience most likely to watch (younger, tech-adjacent, system-skeptical). Salience then hardens into identity: “people like us know the rails are rigged.” Now you’ve got a camp—not red or blue, but anti-establishment with specific villains and fixes.

There’s also reception bias. Fans who come in with progressive anti-corporate priors see a corporate critique; libertarians see a state-surveillance critique; accelerationists see a case for smashing the wheel. The same text validates different camps, and social media funnels each group into creators who reinforce its read. Before long, the Mr. Robot hashtag ecosystem becomes a belief refinery: clips → takes → merch → influencers → meetups → policy preferences. That’s a propaganda pipeline, even if no one signed a memo.

The show’s technical plausibility (honeypots, femtocells, UPS exploits, title ledgers) is another persuasion vector. When details track real white papers, the brain lowers its guard and accepts adjacent normative claims: “these institutions are beyond reform,” “disruption justifies collateral damage,” “data lords are the true sovereigns.” Accuracy of mechanism can smuggle in overreach in meaning—and audiences rarely separate the two.

Finally, catharsis can be a control tool. The series offers an emotional outlet for institutional anger—righteous speeches, symbolic takedowns—which can either motivate real-world reform or tranquilize it (“I felt it, so I did something”). Power doesn’t mind safe rebellions that end at the credits. In that sense, even subversive TV can keep viewers inside the cage, trading action for aesthetic.

If you want to watch without getting drafted into a camp, bring a few guardrails:

- Track what the show asks you to feel vs. what it asks you to believe—and which policies those beliefs point toward.

- Separate technical plausibility from political inevitability. Mechanisms can be real while conclusions are optional.

- Ask: whose power grows if this framing spreads? Platforms? Agencies? Certain parties, NGOs, vendors?

- Cross-read with sources outside your tribe; if the show only “makes sense” inside one feed, it’s functioning as team media.

In short: Mr. Robot is both a decoder ring and a recruiting poster. It can teach you where real chokepoints live—and, if you’re not careful, hand you a jersey on the way out. The trick is to harvest the literacy without inheriting the lineup.

Mr. Robot’s first season is a heist told like a fever dream: a handful of outgunned idealists decide to erase consumer debt by corrupting—and then crippling—the world’s most powerful conglomerate, E Corp. It isn’t one hack; it’s a systems operation that mixes social engineering, supply-chain subversion, physical-world sabotage, and narrative control. Here’s how the takedown is designed, staged, and executed across Season 1.

Define the Target: Debt as the Operating System of Control

- Goal: Destroy the records that bind consumers to E Corp—credit cards, mortgages, loans—so the debts become uncollectible.

- Constraint: Those records live in redundant data centers, are mirrored off-site, and are backed up to cold storage. You can’t just “delete a database.” You must also neutralize every safety net that makes deletion reversible.

Assemble the Stack: People, Places, Infrastructure

- Elliot Alderson: Insider access via Allsafe (E Corp’s security contractor), plus the rare blend of coder + social engineer + paranoid ethicist.

- Mr. Robot/fsociety: The mission layer—vision, logistics, safe houses, operational discipline.

- Dark Army (Whiterose): The escalation layer—global routing, timing, and willingness to do what fsociety can’t (or won’t) in the physical world.

- Physical terrain: Coney Island arcade HQ (air-gapped staging), Steel Mountain–style off-site backup fortress, E Corp offices and data floors.

Initial Access: Breach the Edges, Own the Middle

- Phishing and phone pretexting: Elliot profiles targets, breaks weak auth (human and technical), and harvests credentials.

- Insider foothold through Allsafe: The security vendor becomes the Trojan horse; once Allsafe trusts a host, E Corp trusts it by proxy.

- Persistence/backdoors: Implants and scripted callbacks give fsociety time to map networks and plan for the “one bad day.”

Principle: You don’t need zero-days when zero-trust culture is missing.

Kill the Backups: Turn Redundancy into Liability

- Steel Mountain op (social + hardware):

- Socially manipulate front-line staff (Bill Harper) and his supervisor (Wendy) to get physical access to climate controls.

- Install a Raspberry Pi in the HVAC chain to quietly push temperatures toward tape-destroying thresholds.

- Lesson: The cleanest “exploit” is a believable phone call plus a $35 single-board computer.

When the slow-burn HVAC plan risks discovery, the team pivots.

Dark Army Synchronization: Make Recovery Impossible

- BGP / routing pressure & timing windows: Dark Army aligns global network conditions to maximize E Corp’s confusion and minimize failover options.

- Physical disruption as finality: Where heat can’t reach and scripts can’t wipe, explosions do. A tightly timed physical event eliminates a critical backup site—closing the last door E Corp would run through.

Outcome: Even if E Corp restores some systems, the authoritative, reconcile-everything copies are gone or suspect. You can’t collect what you can’t prove.

Information Warfare: Control the Narrative of the Crash

- Brand and theater: fsociety videos, masks, and timed dumps turn a technical outage into a social movement.

- Confidence shock: The attack is framed not as vandalism but as emancipation: “You are free.” That message amplifies panic inside E Corp and patience outside of it—at least long enough for the payload to settle.

Key idea: Markets and states run on belief. The hack aims at ledgers and legitimacy.

Internal Conflicts: Ethics, Identity, and Risk

- Elliot vs. Mr. Robot: The mission’s daemon process (Mr. Robot) keeps the objective online when Elliot’s conscience wants to throttle it.

- Allies with different cost functions: fsociety wants symbolic rupture; Dark Army wants leverage; E Corp’s elites want to survive (and, if possible, profit). The same event serves all three—at different human costs.

The Takedown Event: “One Bad Day”

- Technical: Encrypted/trashed production data, crippled restore paths, confused routing, poisoned trust anchors.

- Physical: Backup site eliminated; Steel Mountain path rendered moot.

- Human: Executives scapegoated, vendors blamed, law enforcement mobilized, and a newly leaderless economy gropes for continuity.

The mission completes not when servers go dark, but when no one can prove what was on them yesterday.

The Aftermath Seeded in Season 1 (What Season 2 Explores)

- Liquidity freezes & rationed cash: Without trusted records, risk models break; ATMs and payment networks throttle.

- Supply-chain knock-ons: Pharmacies, trucking, and small businesses wobble; confidence becomes a public utility in short supply.

- Power adapts: E Corp reframes the crisis to regain leverage; the state hunts for culprits; Dark Army banks favors.

The show’s thesis isn’t “push button: freedom.” It’s: if you topple a pillar, you’d better have built a bridge.

Why the Season 1 Takedown Works (and Hurts)

Works because:

- It attacks redundancy (backups), not just production.

- It blends human and technical vulnerabilities.

- It synchronizes timing across networks and real space.

- It weaponizes narrative, buying crucial hours and attention.

Hurts because:

- The same rails that collect also deliver (payroll, meds, food).

- Confidence collapses downward first—hourly workers and small shops feel it before boardrooms do.

- Vacuums invite the most organized actor to take control—usually not the public.

The Season 1 Lesson

Mr. Robot doesn’t romanticize sabotage; it specifies it. The debt-erasure dream requires more than a brilliant exploit. It demands a post-exploit architecture—payment continuity, legal shields, logistics, and a narrative that protects the vulnerable while the new system boots. Season 1 shows how to pull the plug. The question it leaves you with is the only one that matters:

What comes online next—and for whom?