Introduction:

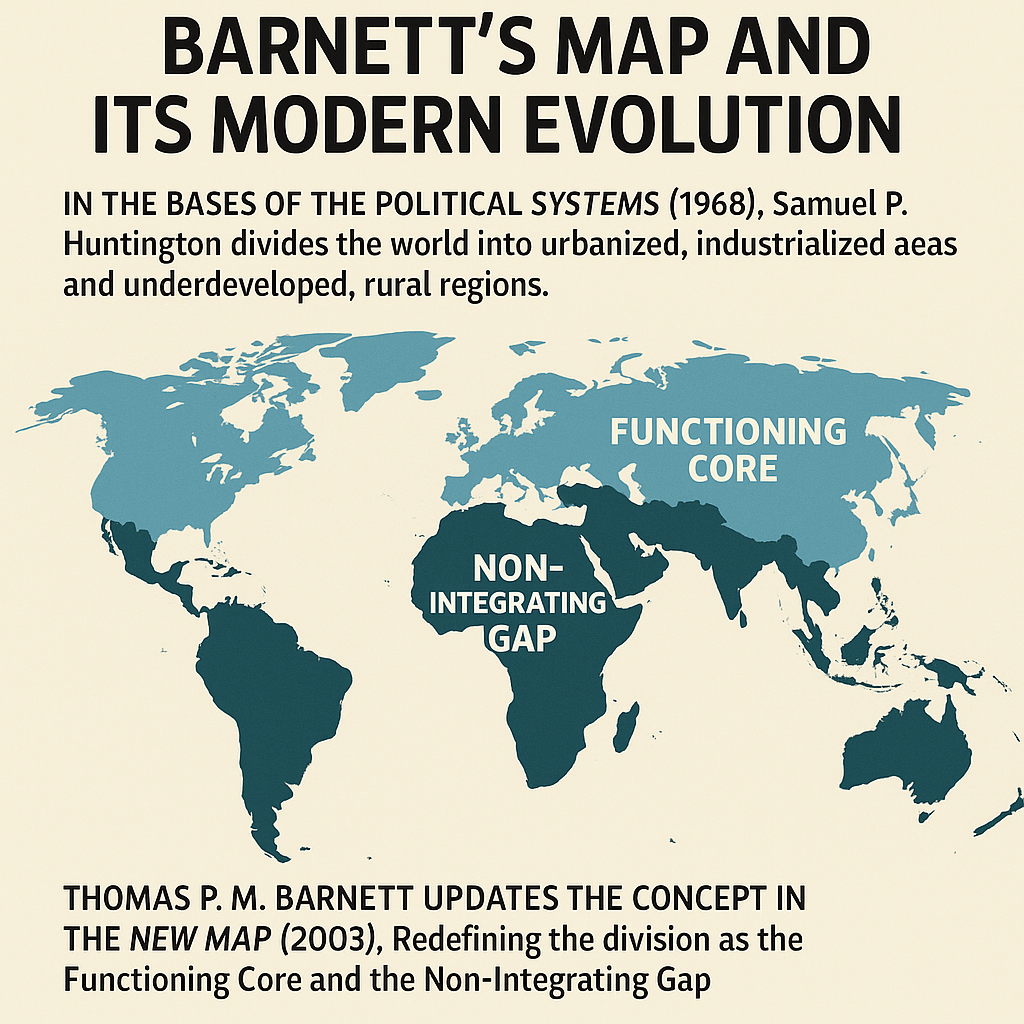

In his seminal work, The Pentagon’s New Map, Thomas Barnett proposed a powerful idea: the world’s security problems stem from a gap between the “connected” and “disconnected” parts of the world. His geopolitical analysis, first articulated in the late 1990s and early 2000s, argued that global stability would increasingly depend on closing this “non-integrated gap”—the areas left outside the growing web of globalization.

- The Pentagon’s New Map: The Hijacking of the US Military

- Who is Thomas P.M. Barnett? Why is it Important?

- Mapping Global Power: From Barnett’s Flows to Today’s Fragmented World (2)

- Global Economic Flows, China’s Rise, and the Evolution of Global Power Structures: From Barnett’s Vision to the Present (3)

- The Fracturing of Globalization: Energy, Urbanization, and the Future of Global Integration (4)

- The Shift of Global Power: Food, Water, Climate, and Demographic Changes from Barnett’s Vision to Today (5)

- The Changing Flow of Global Security: From Atlantic to Pacific and the Rise of New Powers (6)

- Why the 21st Century Will Be the Most Religious Yet: From Survival Codes to Global Spiritual Awakening (7)

- The Fragile Dance of Debt, Power, and Engagement: U.S.-China Relations from Barnett’s Vision to Today (8)

- From Midwives of Integration to Pawns of Multipolar Globalization: Barnett’s Vision and its Evolution (9)

- Timeline Infographic Summary: “Barnett’s Vision to Today’s Global Developments” (Bonus)

Barnett’s thesis was not simply theory — it shaped actual U.S. military strategy and continues to influence policy and the global power balance today.

Barnett’s Core Ideas:

The Functioning Core vs. The Non-Integrated Gap

- Functioning Core: Stable regions integrated into the global economy and governed by predictable, transparent rules. Includes the U.S., Europe, parts of Asia (Japan, South Korea, China increasingly), and rising economies.

- Non-Integrated Gap: Regions outside the globalized system, marked by poverty, conflict, weak governance, and economic stagnation. Includes large portions of Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia, parts of Latin America.

Barnett’s thesis:

“Disconnectedness defines danger.”

Where there’s no strong connection to the global economy, wars, civil unrest, terrorism, human trafficking, drug smuggling, genocide, and poverty thrive.

Globalization’s Engine:

Barnett emphasized that globalization — the flow of capital, people, information, and goods — was transforming the world.

But those left outside the network (the gap) became breeding grounds for violence, extremism, and instability.

Thus, for security and peace:

“The goal of American grand strategy should be to expand the Functioning Core by integrating the Non-Integrated Gap.“

This meant building economic ties, fostering open markets, establishing the rule of law, and — when necessary — using military intervention to stabilize regions (think Balkans, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya).

Why Military Force?

Barnett was not advocating endless war, but he acknowledged reality:

- Some regions are so unstable they cannot integrate peacefully.

- U.S. and allied military intervention would sometimes be necessary to create the conditions for globalization to take root.

- However, force should only be the first step, followed by diplomacy, development, and integration.

He used the Balkans as an example:

“NATO intervention in Kosovo helped create a path to peace and eventual economic development.”

He contrasted that with Iraq and Afghanistan, where overreach and mismanagement led to prolonged conflict.

Barnett’s Map in 2003 vs. the World Today (2025):

| Theme | 2003 Map (Barnett) | Today (2025 Reality) |

|---|---|---|

| Globalization | Core expanding (China rising) | China dominant in Belt & Road, Africa, Latin America |

| Gap | Middle East, Central Africa, Central Asia | Middle East cooling slightly, but new flashpoints in Sahel (Africa) and Pacific tensions |

| Conflict | Afghanistan, Iraq, Sudan, Balkans | Sahel insurgencies, Ukraine-Russia War, Pacific naval tensions |

| U.S. Role | Active military enforcer of integration | Retreating slightly, more “behind the scenes” while China plays bigger global role |

| Technology | Cellphones spreading globalization | AI, internet, digital currencies accelerating connectivity (and conflict) |

Bottom Line:

The Functioning Core has expanded — but new gaps and disconnections have emerged.

Globalization continues, but with more players (China, India) and new risks (AI surveillance, cyber warfare, global pandemics).

Present Challenges:

China’s Rise:

- China took Barnett’s blueprint seriously: integrating disconnected regions (Africa, Latin America, Belt & Road countries) into its economic orbit.

- China offers infrastructure, loans, and trade — but often without demanding democratic reforms or human rights accountability.

Fragmentation of the Core:

- The “Old Core” — U.S., Europe, Japan — is fracturing politically (Brexit, U.S. populism, European divisions).

- Trust in global institutions like the UN, WTO, and IMF is declining.

New Gaps Emerging:

- Climate change, pandemics, cyber insecurity are creating new disconnected zones.

- Even within Core countries, rural areas are “gap-like” compared to hyper-connected cities.

How Barnett’s Vision Has Evolved:

Barnett was optimistic that peaceful globalization would dominate.

But he underestimated:

- The resilience of authoritarian regimes like Russia and China.

- The backlash against globalization from those feeling economically and culturally left behind (populism).

- The weaponization of technology (AI surveillance, misinformation) by global actors.

Instead of simply bringing peace, globalization has multiplied vulnerabilities — supply chain dependencies, information warfare, and financial instability.

Lessons for Today:

- Connectivity is not neutral.

It can empower both democracy and authoritarian control. - Economic integration must be accompanied by moral and political integration.

Trade alone doesn’t create freedom. - Ignoring the Gap breeds instability.

Failed states, refugee crises, pandemics — these arise from gaps. - U.S. strategy must balance engagement and resilience.

Overreaching (Iraq) backfires, but total disengagement (Afghanistan pullout) also destabilizes. - The next frontier: Cyber, AI, and Biotech.

Disconnectedness now includes digital exclusion and biosecurity vulnerabilities.

Conclusion:

Thomas Barnett’s “Gap” theory remains a critical lens for understanding global conflict today.

The world is more connected, more unstable, and more multipolar than it was in 2003.

America is no longer the sole “system administrator” of globalization.

Instead, power, connectivity, and influence are spreading to many hands — some of them benign, many dangerous.

If the 21st century is to avoid devastating global conflict, the world must manage how it connects — not just that it connects.

The future depends not just on shrinking the Gap, but on bridging it with wisdom, justice, and respect for human dignity.