A Harder Story of First Contact

For most of us, the version of history we learned about America’s frontier was tidy, emotional, and moralized. It gave us heroes and villains, victims and conquerors, and a sense of closure: feel guilty, feel enlightened, move on. But truth doesn’t live in that simplicity. History is harder, more human, and far more instructive when we face it without the filters of sentiment or ideology.

The story of Native America isn’t about replacing one myth with another—it’s about reclaiming accuracy from propaganda. Before Columbus, North America was already a mosaic of empires, alliances, betrayals, and complex civilizations. Europeans didn’t create chaos from order; they collided with a world that already knew diplomacy, war, slavery, and survival. What they brought was scale: industrialized conquest, bureaucracy, and an ideology that could erase entire nations by statute rather than sword.

Reading this history with clear eyes doesn’t diminish anyone’s courage—it expands our empathy. We see that humanity, in all its beauty and brutality, existed on every side. It wasn’t simply “good natives” and “bad settlers.” It was a collision of codes, a clash of worldviews, and a tragic escalation driven by fear, pride, misunderstanding, and ambition.

When we see the full picture, we stop treating history as therapy and begin treating it as wisdom. We learn how easy it is for every civilization—including ours—to justify conquest in the name of progress, or to trade freedom for safety. Understanding what happened on the frontier is not about the past—it’s a mirror for the present.

If we can confront the myths that shaped our national identity, we can start to rebuild a deeper kind of patriotism: one that honors truth over comfort, courage over pride, and reconciliation over revisionism. Seeing clearly isn’t guilt—it’s growth. And that’s the beginning of healing, both for the stories we tell and the country we’re still becoming.

For years, many of us absorbed a tidy morality play: peaceful Native peoples living in harmony until rapacious Europeans arrived and wrecked paradise. It offers catharsis—feel bad, feel enlightened, move on. But it isn’t history. North America before 1492 was already a hard world of rival nations, diplomacy and betrayal, raiding economies, and long blood feuds. Europeans didn’t introduce violence; they collided with it—and then scaled it.

This isn’t about swapping heroes and villains. It’s about telling a truer, harder story so we can actually understand what happened.

Before Columbus: When Raiding Was a Résumé

Across many regions, young men proved themselves on raids. Success—stealing horses, taking captives, bringing home scalps—translated into status, marriage prospects, and political influence. Captives might be enslaved, adopted to replace lost kin, or ritually tortured—public ordeals that tested the victim’s stoicism and the community’s resolve. Scalping predated Europeans (archaeological evidence for pre-contact scalping and mass violence includes sites like Crow Creek, c. 1325). Violence wasn’t universal or constant, but in large swaths of the continent it functioned as social currency and a recognized means of restoring balance after loss.

Just as important: there were rules. The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) waged “mourning wars” governed by custom; Southeastern chiefdoms fortified towns and rotated fields knowing when fighting seasons peaked; on the Northwest Coast, raiding and slaving coexisted with potlatch diplomacy and strict hierarchies. None of this fits the Edenic picture—but neither does it reduce Native societies to caricatures of bloodlust. These were political cultures managing scarcity, grief, honor, and power.

Two Codes of War Collide

Europeans arrived with Old World expectations—declarations of war, uniforms, terms of capitulation, categories of “combatant” and “civilian” (honored imperfectly, but encoded in law and custom). Frontier warfare ignored much of this. Small, mobile Native war parties prized speed and surprise; night attacks, ambushes, and the taking of captives were part of the logic of war. To British officers trained for set-piece fights, this looked like terror. To many Native leaders, lining up in open fields or “surrendering” under a white flag looked suicidal or senseless.

The meaning of land also clashed. European settlers treated land as alienable property; many Indigenous polities treated it as a shared, traversed domain with layered, seasonal rights. A treaty ceding “title” in European eyes might be understood locally as granting limited passage or shared use.

Once contact deepened, both sides adapted. Colonists formed ranging companies (Rogers’ Rangers in the northeast, later the Texas Rangers in the southwest). Colonial governments posted scalp bounties, monetizing a practice that already existed but now paid cash. Native fighters sought or shunned European alliances as it suited their own enemies. The old rules eroded; new incentives intensified the fight.

Adaptation and Escalation

Disease and trade transformed strategy. Epidemics shattered populations and reshaped power; those closest to European posts gained firearms and leverage, setting off chain reactions across the interior.

- Pequot War (1636–37): English and Native allies destroyed fortified Pequot towns (Mystic) with fire and slaughter—an early example of European forces adopting total-war tactics on the frontier.

- Beaver Wars (17th c.): The Haudenosaunee pursued fur-trade hegemony, dispersing rivals and remapping the Great Lakes interior.

- King Philip’s War (1675–76): In New England, Wampanoag-led coalitions devastated towns; colonial retaliation depopulated Native communities, leading to enslavement and diaspora.

- Yamasee War (1715–17): A multi-tribal revolt against Carolinian trade abuses nearly erased the colony, showing Native coalitions could threaten colonial survival.

- Pontiac’s War (1763–66): A broad uprising after the Seven Years’ War reminded the British that “victory” over France didn’t mean consent from the interior nations.

- Sullivan Expedition (1779): The Continental Army burned Haudenosaunee towns and crops—starving a foe rather than defeating them in battle.

Civilians bore the worst of it. Raids targeted farms and outlying settlements; militias and volunteers answered with massacres and “exemplary” violence. Treaties served more as pauses than peace.

Case Study: The Comanche Ascendancy

By the late 1700s, the most feared military power west of the Mississippi wasn’t Spain, France, or Britain—it was the Comanche. Originally part of the Eastern Shoshone, they moved south and onto the plains, adopting the horse with breathtaking speed. Mastery of mounted archery and later firearms turned bands into the core of a raiding-and-trading empire that dominated Comanchería for roughly 150 years.

- Tactics: A warrior could hang off the far side of his galloping horse, using the animal as a shield while loosing arrows—then wheel and disappear. Mobility, intelligence networks, and dispersed logistics made them maddening opponents for lumbering armies.

- Political economy: Comanche power mixed tribute, trade, and predation. Raids reached deep into New Spain; peace deals with New Mexico alternated with devastating forays. Captives were integrated at scale—adopted, ransomed, or enslaved—feeding labor needs and diplomacy.

- The turning: Repeating rifles, winter campaigns, and the near-extermination of the buffalo by commercial hide hunters undercut Comanche mobility and provisioning. Epidemics did the rest. By the mid-1870s, bands surrendered under crushing material realities, not because they lacked courage or skill.

Another Lens: Revolt and Statecraft

It wasn’t all raiding ascendancy. Native alliances repeatedly reversed colonial momentum.

- Pueblo Revolt (1680): Coordinated attacks expelled the Spanish from New Mexico for over a decade, the most successful anti-colonial revolt in North America.

- Haudenosaunee diplomacy: A confederacy of nations used councils, condolence rituals, and strategic neutrality to outlast European empires and bargain from strength for generations.

- Cherokee and Creek diplomacy: Southeastern nations played British, Spanish, and later American interests against one another, leveraging trade and treaty to protect homelands—until American demography and policy overwhelmed diplomacy.

Blood on Both Sides

The frontier is thick with episodes that defy easy moral sorting: the 1637 Mystic massacre, 1704 Deerfield raid, the 1764 Paxton Boys’ murders, the 1782 Gnadenhütten massacre of Christian Lenape, Sand Creek (1864), Bear River (1863), Washita (1868), and Wounded Knee (1890); on the other side, raids that included torture, gang rapes, and killings of noncombatants. The 1862 Dakota War killed hundreds of settlers (including infants), followed by mass executions and expulsion. Both sides broke agreements; the United States signed hundreds of treaties and, as power shifted, violated or reinterpreted most.

Naming this does not flatten guilt; it situates actions in a long, escalating cycle where atrocity bred atrocity and civilians were the softest target.

The Deadliest Weapon Wasn’t a Weapon

The greatest killer was disease. Smallpox, measles, influenza, and other “virgin-soil” epidemics tore through communities with no prior exposure. Mortality rates often exceeded half; in some places they were far higher. Epidemics recurred—smallpox waves in the 16th century, the 1780–82 plains outbreak, the devastating 1837–38 Missouri River epidemic. War magnified famine and exposure, and vice versa, but microbes did most of the demographic work.

Deliberate spread was rare (notorious allegations surround a 1763 incident at Fort Pitt); most contemporaries reached for fatalism—“providence” or “fate”—a grim rationalization that changed nothing on the ground.

Law, Removal, and the Scaling of Power

What Europe (and the United States) added was state capacity tethered to mass settlement:

- Survey and statute translated conquest into plats, patents, and sheriffs.

- Finance and logistics moved armies, annuities, and bureaucrats across a continent.

- Ideology—from “civilization” programs to racial pseudo-science—justified removal, allotment, boarding schools, and bans on ceremony and language.

- Indian Removal (1830s): “Treaties” like New Echota, enforced marches like the Trail of Tears, and later allotment under the Dawes Act fragmented landholding and sovereignty in ways no pre-contact warfare ever could.

That is the “scaling” part. The state could do, predictably and repeatedly, what no raiding party could: move entire nations, police borders, erase titles, and reshape childhoods.

Numbers, Uncertainty, and Humility

Pre-contact population estimates vary widely; scholars often center the area of the modern United States in the mid-single-digit millions, with North America as a whole plausibly in the low tens of millions. Battle deaths are hard to separate from deaths by disease, exposure, and starvation. What’s clear: the violence stretched over centuries and across the continent, and the human toll was immense.

Precision isn’t the point; humility is. A harder story accepts uncertainty without retreating into myth.

Why the Simplified Story Persists

Simple stories comfort the living and flatter the tellers. They travel better in classrooms and films. But they flatten cultures—turning Native peoples into cardboard saints or permanent victims, and settlers into mustache-twirling caricatures. The real frontier featured muscular civilizations colliding until one had more people, more guns, and an industrial state behind it.

How to Teach It Better

- Show both codes of war. Pair Jesuit Relations or colonial codes of conduct with Native accounts of mourning war and raiding logic; let students see the clash of norms.

- Trace reprisals. Build timelines (raid → retaliation → raid) for specific regions; make civilian vulnerability visible.

- Use case studies. Comanchería for mobility and political economy; the Pueblo Revolt for anti-colonial coordination; the Beaver Wars for trade and hegemony.

- Center disease honestly. Distinguish unintended epidemic from deliberate atrocity without minimizing either.

- Follow captives’ lives. Stories like Cynthia Ann Parker and Quanah Parker complicate “rescue” narratives and show the porousness of identity.

- Be precise with terms. “Genocide,” “ethnic cleansing,” “war,” and “massacre” have definitions—use them carefully and consistently.

- Keep sovereignty in view. Treaties are law (in U.S. constitutional terms, “supreme law of the land”); show how they were made, broken, and litigated—and how they still matter.

The Hard Respect History Demands

If you want to honor Native Americans, don’t mythologize them. Acknowledge power, resilience, statecraft, spirituality, commerce—and yes, brutality where it existed. Do the same for settlers. History isn’t therapy; it’s memory with evidence. When we tell it straight, we lose the comfort of easy blame—but we gain understanding worthy of the people who lived, fought, suffered, adapted, negotiated, and endured on both sides of the line.

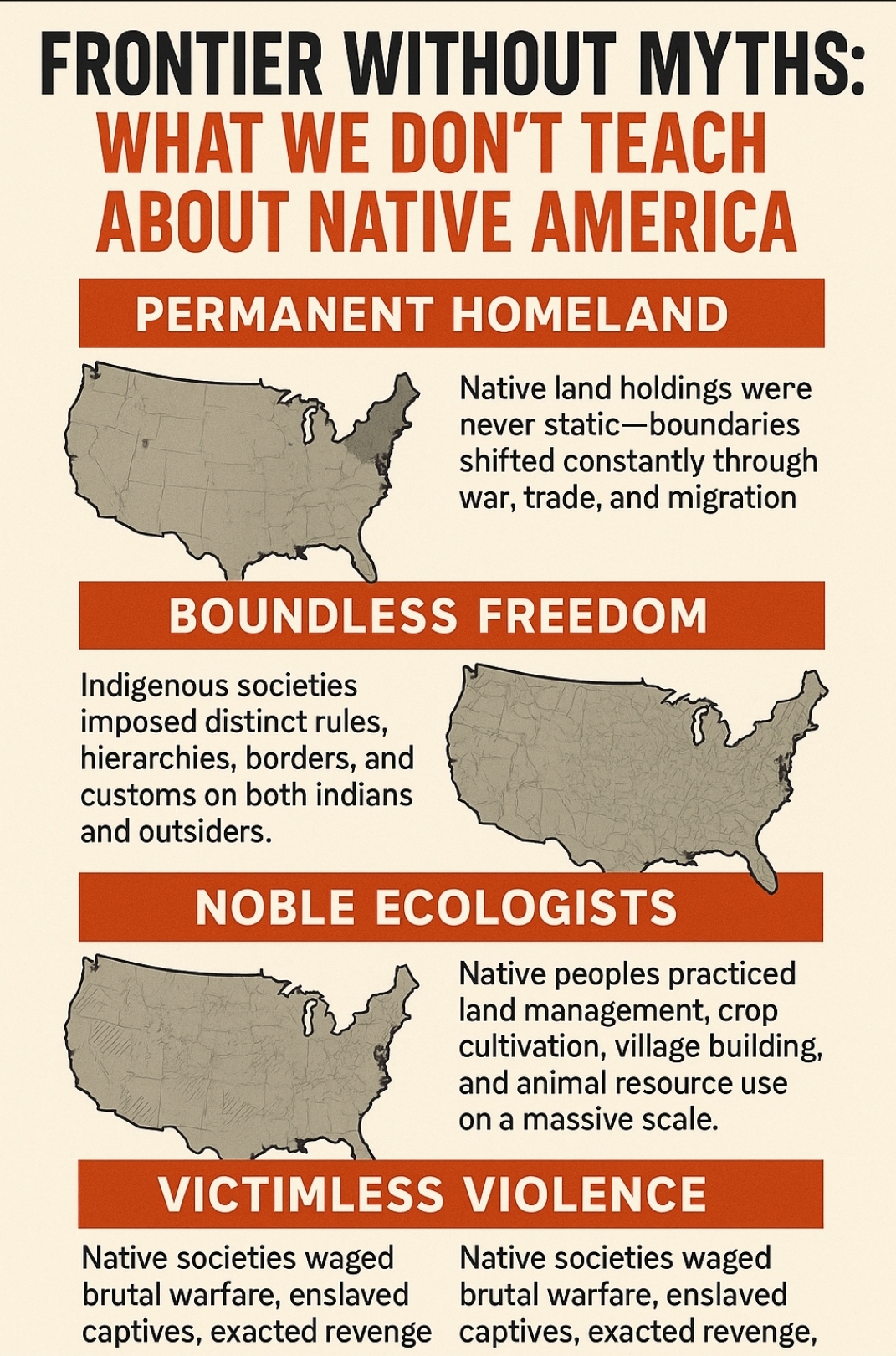

Ken LaCorte’s “What They Don’t Teach You About Native Americans” (Elephants in Rooms), following the flow of the transcript you shared:

Thesis & setup

- We’re taught a simple morality play: peaceful natives vs. greedy Europeans.

- LaCorte argues that’s false: North America was already violent; the frontier became a clash of two brutal systems, producing centuries of raids, reprisals, and massacres with “no one walking away clean.”

- Goal stated: not to create new villains/victims, but to face awkward realities.

Before Columbus: violence as social currency

- For many tribes, raiding was central to male status—proof of bravery, a path to marriage, respect, and reputation.

- Raids were frequent (seasonal, sometimes weekly). Captives might be adopted, enslaved, or tortured to death in public rites.

- Torture framed as ritual/test of courage; victims who endured stoically gained honor (for themselves and the community).

- Scalping predated Europeans; it functioned as trophy, proof, and humiliation. Scalps of women/children signaled a warrior had penetrated to the heart of a village.

- Example: Crow Creek (S. Dakota), early 1300s—~500 massacred, widespread scalping signs.

Cycles, scale, and intertribal wars

- Violence was cyclical: one raid demanded revenge; feuds could last generations.

- Scale spanned centuries and the continent; some episodes approached genocide.

- Examples:

- Iroquois “Beaver Wars” (1600s) displacing/wiping out dozens of tribes from Great Lakes to Ohio.

- Sioux expansion west by brutalizing other nations.

- Caveat: violence was widespread, not universal—some tribes were peaceful at times.

Europeans arrive: clashing codes & worldviews

- Europeans brought Old World “rules of war”: uniforms, declarations, soldier-to-soldier battles, civilians relatively off-limits (in theory).

- Frontier reality: native warfare looked like today’s “terror tactics” to colonists—small raiding parties, surprise at dawn, quick vanish, civilian targeting, captives.

- To natives, European habits (lining up, defending forts, seasonal pauses, white flags) seemed naïve/alien; surrender didn’t mean mercy.

- Land: Europeans saw property/fences/inheritance; many tribes viewed land like the open sea—used, not owned.

- Spirituality in war: charms/war paint/omens sometimes bred overconfidence or sudden retreats.

- European methods failed against mobile fighters; settlers adapted.

Adaptation & escalation (Rangers)

- Colonists formed ranging companies optimized for frontier fighting—trackers, scouts, fast strikes.

- Texas Rangers evolve from this model.

- Tactics converged: settlers burned crops, took scalps, hit villages—rules they once condemned became SOP.

- Result: both sides increasingly targeted civilians; atrocity/retaliation spirals deepened.

Case study: The Comanche “empire”

- Peak numbers ~40,000; dominated territory across TX/NM/CO/KS/OK for ~150 years; extracted tribute, controlled passage.

- Mastery of the horse transformed warfare: childhood training, acrobatic mounted archery (e.g., hanging off the horse’s side, rapid fire).

- Culture valorized raiding and ruthlessness; called the “Mongols of the Plains.”

- 1840 “Great Raid” into Mexico: villages destroyed, thousands of horses taken, captives dragged north; Mexico’s northern frontier collapses.

- Captives 10–25% of Comanche communities; widespread slave-taking/trade (Native/Mexican captives).

- Cynthia Ann Parker: captured at 9, assimilated, married a chief, “rescued” after 24 years but resisted; mother of Quanah Parker (last great Comanche chief).

- U.S. Army struggled for decades; conventional chase failed (“fighting shadows”).

- Turning points: population decline (war/disease), repeating rifles, mass bison slaughter by hide hunters (with Army tolerance), failed Comanche attack on Adobe Walls (1874), Col. Ranald Mackenzie’s brutal winter campaign (burning stores, destroying ~1,000+ horses). Final surrenders followed.

Atrocities on both sides (illustrative examples)

- Mormon militia disguised as Indians massacres ~120 civilians (Mountain Meadows).

- Tucson citizens & allies kill 100+ peaceful Apache (women/children).

- Comanche raid on Fort Parker included gang rapes and killings.

- 1862 Dakota (Sioux) Uprising kills 600+ settlers, including infants.

- Treaties: both sides broke them; LaCorte claims the U.S. negotiated 500+ and “effectively broke every single one.”

Demography & death tolls (broad estimates)

- Pre-Columbian Native population: often cited around ~10 million (with wide uncertainty).

- European population remained smaller until early 1800s, then surged via immigration.

- War deaths across 300 years: “hundreds of thousands” of Natives; “tens of thousands” of Europeans (hard to separate from famine/disease).

- Primary killer: disease. Smallpox, measles, influenza cause an estimated 60–90% of Native deaths.

- Intentional germ warfare: one documented 1763 smallpox-blanket episode; otherwise disease spread was not deliberate in his telling—seen as fate/Providence by many settlers.

Narrative frames & moral

- Each side told itself the same story: we’re the victims; they’re the monsters; they started it; we’ll finish it.

- Frontier reality: two muscular cultures collided until one had more people and better guns.

- Respect Native Americans without turning them into cardboard saints or eternal victims; acknowledge power, resilience, and—often—brutality, just like the settlers.

Epilogue

- Book rec: Comanches: The History of a People (the video’s inspiration).

- Teaser to a related “elephant in the room”: why child soldiers are used—morally horrific but strategically “effective.”