The moment I heard about the assassination of Charlie Kirk, my mind didn’t linger on the headlines—it went instantly to history. I thought of JFK, Martin Luther King Jr., and every carefully staged tragedy that followed the same choreography: a shockwave, a suspect, and a story assembled almost too quickly to question. Then I found myself re-watching Captain America: Civil War, not as escapism, but as diagnosis. The film’s emotional engine—the framing of Bucky Barnes for a bombing he didn’t commit—feels less like fiction and more like a mirror held up to how power manages public grief.

In Civil War, we watch a world desperate for answers accept the first, easiest narrative: Bucky is the bomber; vengeance is justice. The truth—buried beneath layers of manipulation and media spin—takes patience, conscience, and courage to uncover. It’s the same rhythm that followed the murders of Kennedy and King: confusion, fear, a villain packaged for prime time, and a populace too heartbroken to slow down.

Hollywood revisits this moral equation often because it’s ancient and unresolved. Shooter, Enemy of the State, Minority Report, and Civil War all ask the same question: what happens when power writes the script of guilt before the evidence appears? Each story reminds us that framing isn’t just a plot device—it’s a strategy of control. The real killer, whether in the shadows of Washington or the alleys of a Marvel set piece, depends on one reflex: our willingness to believe the first version of the truth that makes our grief feel organized.

And so the pattern repeats—on screen and off—testing whether we have learned to pause, to doubt, and to look beyond the frame.

When Captain America: Civil War pins the Vienna bombing on James “Bucky” Barnes, it gives us more than a plot twist. It offers a civic lesson: in moments of shock, the first tidy story often beats the truest one. A grainy clip, a familiar villain, a high-profile victim—suddenly the world is sure it knows what happened. The rest of the movie is a race between spectacle and verification.

That tension echoes through real life. After any political killing or high-stakes attack, narratives harden quickly: press conferences, headlines, trending clips, “case closed.” We’ve seen how that works historically in the debate over the JFK assassination, and we see versions of it whenever a public figure is murdered or dies under contested circumstances. The lesson isn’t to embrace conspiracies; it’s to slow down and demand evidence that can stand up to cross-examination.

This article uses the Bucky setup as a clean template for thinking clearly when the stakes (and emotions) are high.

How a Frame Job Works (The “Bucky Template”)

1) A compelling image outruns context.

Officials “release video”; media loops a snippet; the public sees enough to feel certain.

2) A symbolic casualty compresses time.

The more beloved or important the victim, the stronger the pressure to act now. Deliberation looks like disrespect.

3) A pre-loaded villain fits the story.

Someone with the means, the history, and the face becomes the path of least resistance.

4) Pain becomes policy.

Calls for “order” yield new powers, constraints, designations—sometimes necessary, often hasty.

5) Later forensics tell a messier story.

When the dust settles, chain-of-custody gaps, manipulated context, or alternative timelines appear. By then, careers and policies are invested in the first version.

In Civil War, Zemo exploits each step: he manufactures the image, times it to maximum outrage, and lets institutions do the rest. Steve Rogers’ stubbornness—refusing to outsource conscience—buys time for the truth.

Why We Fall for Fast Stories

- Pictures beat paragraphs. We trust what we see, even when the angle is curated.

- Grief simplifies judgment. Mourning and fear make nuance feel like betrayal.

- Authority signals certainty. Badges and logos confer borrowed credibility.

- Cognitive economy. One villain + one motive is easier than a complex chain of events.

None of this means the first suspect is always wrong. It means epistemic humility—the discipline to separate facts from claims and inferences—is the adult response to shock.

A Layperson’s Checklist: “How to Think After an Assassination”

Evidence chain

- Who captured the key video/audio? Who edited it? What’s outside the frame?

- Are timestamps, locations, and metadata verified by multiple independent analysts?

Witness discipline

- Distinguish eyewitness, hearsay, and on-background claims.

- Are interviews recorded and consistent across retellings?

Forensics & timelines

- Do ballistics, entry/exit paths, comms logs, and travel records align?

- Are there gaps prosecutors acknowledge and plan to resolve?

Motive vs. mechanism

- “Who benefits?” is a hypothesis generator, not proof.

- Means + opportunity + verifiable steps matter more than motive narratives.

Process safeguards

- Are disclosures staged (timeline, exhibits, redaction reasons)?

- Is there independent review? Can defense teams test key claims?

Media hygiene

- Headlines should label content: reporting, analysis, or opinion.

- Beware certainty words (“prove,” “definitively”) attached to partial evidence.

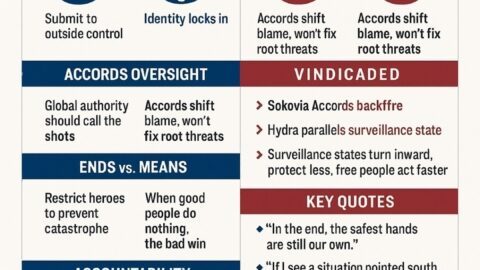

Why Captain America’s Ethic Matters

Steve Rogers’ line—“The safest hands are still our own”—doesn’t mean “no rules.” It means don’t subcontract your moral judgment to a committee when evidence is thin and pressure is high. In the film:

- He seeks verification before condemnation.

- He treats the accused as a person, not a press packet.

- He accepts personal risk to keep truth from being steamrolled by optics.

That posture is precisely what healthy institutions require. Oversight and accountability are vital, but they must serve truth—not replace it. When we let panels, platforms, or press cycles tell us that speed equals justice, we invite the abuse the Founders tried to prevent: power wielded on the momentum of grief.

JFK as the Enduring Caution

Decades after President Kennedy’s assassination, debate persists not because “nothing is true,” but because evidence, procedure, and transparency were—and remain—imperfect. The durable lesson is procedural: if you want public trust later, build rigorous, transparent processes now. Publish timelines, preserve records, welcome qualified adversarial review. Precision beats narrative.

Bringing It Home

When a public figure is killed, the temptation is to join the nearest chorus. Resist it. Grieve, then verify. Demand receipts: chain-of-custody, forensics, corroborated timelines. Support oversight that tests claims rather than pre-endorses them. Reward leaders who can say “I don’t know yet” and later update the record openly.

Civil War isn’t asking us to idolize vigilantes. It’s warning us about the civic costs of fast certainty. Bucky’s story ends with the truth surfacing, but only because someone slowed the stampede.

That’s our job when the stakes are real:

Don’t be the echo. Be the brake.

Don’t trade truth for speed.

And never let grief do the thinking that evidence must do.