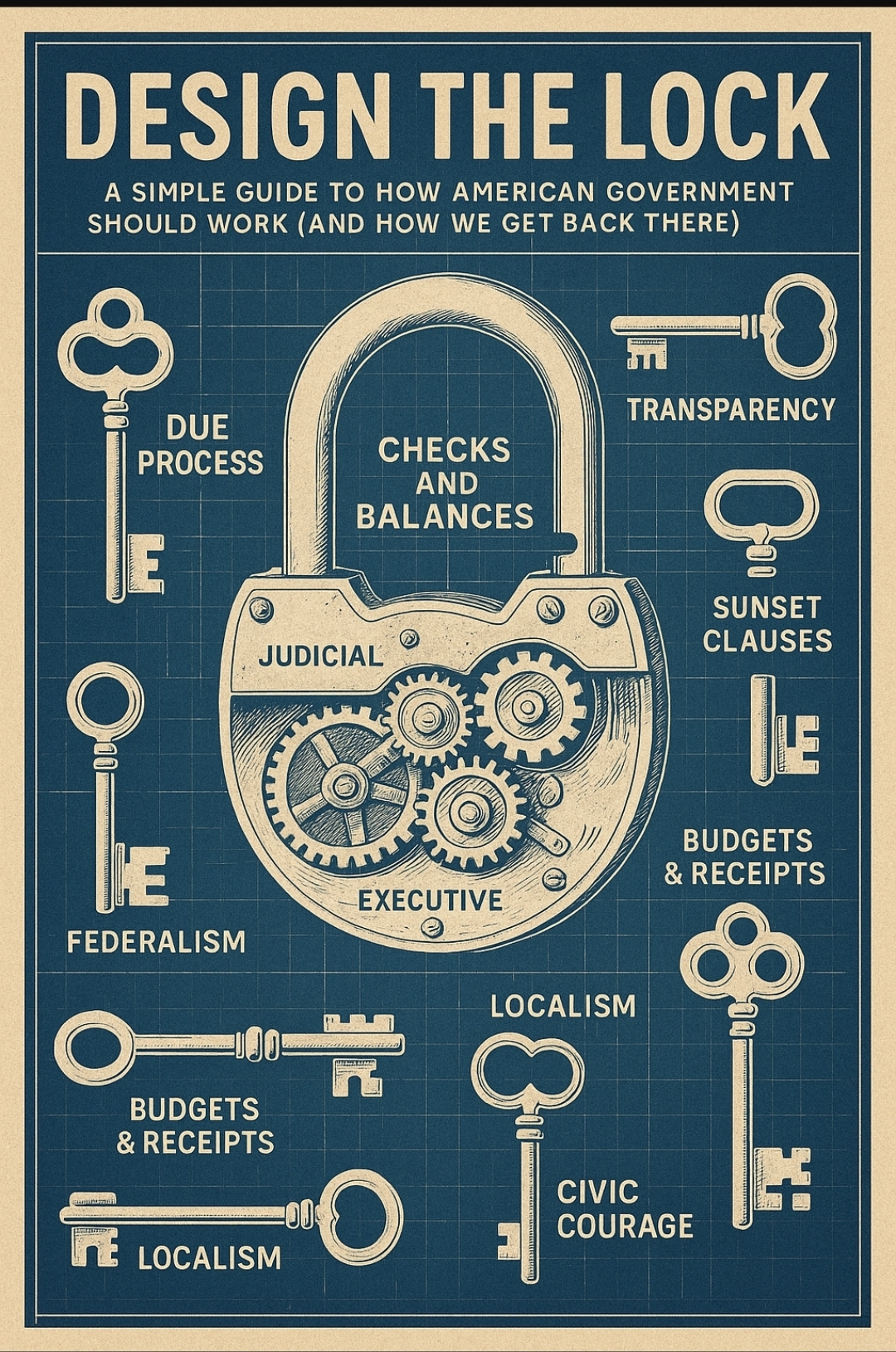

Rule #1 of Good Design: Plan for the Worst Hands

Principle: “If the worst person here ran this, how could they abuse it?” Then design the lock.

That’s not cynicism; it’s constitutional wisdom. The American Founders assumed human nature is mixed—capable of virtue and vice—so they built systems that work even when good people aren’t in charge.

This article walks through how that mindset shaped early state constitutions, the Articles of Confederation, and finally the U.S. Constitution—and how we drifted from it, plus practical ways to refocus on it today.

The Design Mindset: Ambition vs. Ambition

The core insight: don’t rely on angels. Rely on architecture.

- Separate powers so no one actor combines lawmaking, law-enforcing, and law-judging.

- Check and balance each branch so ambition restrains ambition.

- Divide sovereignty (federalism) so local powers counter national ones.

- Bind government with rights (due process, jury trials, speech, press, religion, arms, security from searches) so citizens have tools when government forgets its limits.

In short: put a lock on every likely path to abuse—and give the people the keys.

First Drafts: The State Constitutions (1776–1780)

Before the federal Constitution, states did the prototyping.

- Written limits and bills of rights: Many states codified explicit rights (jury, press, conscience), assuming future rulers might not be benevolent.

- Frequent elections & short terms: Rotate power before it calcifies.

- Plural executives & councils (in some states): Don’t bet freedom on a single personality.

- Independent courts: Keep referees who aren’t on a team.

Design lock: If the worst governor showed up, they still had to get past elections, courts, and a legislature—and citizens retained concrete rights as tripwires.

The Articles of Confederation: Overlocking the Center

The Articles (1781–1789) were a deliberate under-build at the national level:

- No independent executive, no national judiciary, and weak taxing power.

- Unanimity/near-unanimity for big changes.

What worked: It was nearly abuse-proof at the center.

What failed: It was also action-proof—struggling with revenue, defense, and interstate friction.

Lesson: A good lock must still allow legitimate use. Security that prevents function isn’t good design.

The U.S. Constitution: Balanced Locks, Working Machine

The 1787 Constitution tries to keep the locks while restoring capability:

- Separation of powers: Congress (laws/purse), President (execution/veto), Courts (judgment/judicial review).

- Checks & balances: Veto/override, confirmations, impeachment, judicial independence.

- Federalism: National powers enumerated; states retain vast police powers.

- Rights as hard stops: No bills of attainder, no ex post facto laws, habeas corpus protections; later, the Bill of Rights adds strong locks at the citizen level.

- Different selection & terms: House (short terms), Senate (staggered), President (fixed term), Courts (tenure during good behavior). The varied incentives prevent synchronized capture.

Design lock: If the worst actor captured one branch, others could slow or stop abuse—while the system still had enough power to govern.

Where We Drifted from “Design the Lock”

Over time, convenience and crisis chipped away at the locks:

- Emergency powers without sunsets: Temporary becomes permanent.

- Administrative sprawl: Broad delegations let agencies make quasi-laws with less legislative accountability.

- War powers drift: Long conflicts driven by open-ended authorizations dilute Congress’s check.

- Omnibus lawmaking & urgency theater: Complexity hides trade-offs and enables logrolling.

- Mass surveillance & data hoarding: New tech without old locks (warrants, minimization, deletion-by-default).

- One-party entrenchment tactics: Gerrymanders and closed primaries reduce electoral checks.

Pattern: We trusted “good people” and ignored the question, “What could the worst do with this?”

The Core Idea: Assume the Worst, Protect the Best

Think of government like a house with kids and strangers constantly coming and going. You don’t rely on everyone being good; you child-proof, you lock cabinets, you label the meds, and you separate keys. The Founders did the same with power:

- Separate the keys (separation of powers)

- Make people check each other (checks & balances)

- Don’t put everything in one room (federalism & local control)

- Publish the house rules (a written Constitution)

- State the “absolutely nots” (Bill of Rights)

Design for human nature, not angelic behavior.

Refocusing Today: Put the Locks Back On

Here are practical, nonpartisan ways to restore the principle across law, policy, and tech.

Laws & Institutions

- Sunset everything “emergency.” Expire by default; renewal requires fresh votes and public findings.

- Single-subject, readable bills. No more omnibus Christmas trees.

- Regular order budgeting. Force line-by-line trade-offs in daylight.

- Tight delegation with guardrails. Clear statutory limits, measurable standards, judicially reviewable.

- Rebalance war powers. Narrow authorizations, periodic re-approval, defined missions and metrics.

- Independent, adversarial oversight. IGs with teeth, protected whistleblowers, transparent audit trails.

- Open courts for rights-restricting actions. Secret processes must be narrow, timed, and reviewable.

Data & Technology

- Data minimization & deletion-by-default. You can’t abuse what you don’t store.

- Split-key authority for sensitive actions. No single official can flip the switch.

- Immutable public logs for high-risk decisions. After-action review must be possible.

- Red-team before rollout. Assume worst-case actors; try to break the system.

- Privacy-by-design & warrant-by-design. Make lawful process the path of least resistance.

Elections & Civic Culture

- Independent redistricting & open primaries. Reduce incentive to appeal only to extremes.

- Civic literacy upgrades. Teach locks-and-keys, not just slogans.

- Transparency you can actually read. Plain-language summaries, machine-readable data, searchable votes.

A Simple Checklist for Any Policy or Platform

- Worst-Hands Test: What could a bad actor do on Day 1 with this power?

- Misuse Map: List abuse paths; add specific countermeasures for each.

- Proof of Locks: Show the sunset, the audit path, the split controls, and the appeal route.

- Open the Books: Publish what you can, and time-limit what you can’t.

- Practice the Failure: Run drills for abuse scenarios; measure detection and recovery time.

The Payoff

Designing for the worst hands protects the best hopes: fair laws, trustworthy institutions, resilient rights. It’s how early Americans thought, and it’s how durable systems in any era must be built.

Good design doesn’t assume saints.

It expects sinners—and still keeps the lights on.

Rule #1 of good design: “If the worst person here ran this, how could they abuse it?” Then design the lock.

That’s not cynicism. It’s wisdom. And it’s exactly how America’s early governments tried to think.

This article explains—in plain language—how that mindset shaped early state constitutions, then the Articles of Confederation, and finally the U.S. Constitution. It also shows how we drifted from the principle, and how we can refocus on it today.

The Core Idea: Assume the Worst, Protect the Best

Think of government like a house with kids and strangers constantly coming and going. You don’t rely on everyone being good; you child-proof, you lock cabinets, you label the meds, and you separate keys. The Founders did the same with power:

- Separate the keys (separation of powers)

- Make people check each other (checks & balances)

- Don’t put everything in one room (federalism & local control)

- Publish the house rules (a written Constitution)

- State the “absolutely nots” (Bill of Rights)

Design for human nature, not angelic behavior.

How We Got Here: States → Articles → Constitution

Early State Constitutions (1776–1780s)

The colonies-turned-states tried different setups. Most feared governors becoming mini-kings, so they weakened executives and empowered legislatures. Good lock against one person—but sometimes too weak to act decisively.

Articles of Confederation (1781–1789)

The first national plan made the center so weak it couldn’t collect taxes or coordinate well. Great at preventing a national tyrant; bad at handling shared problems (war debts, trade disputes). We needed a better lock—not no lock.

U.S. Constitution (1789– )

The fix wasn’t to trust leaders more. It was to balance power better:

- Congress (makes laws & controls the money)

- President (executes laws; checked by Congress & courts)

- Courts (interpret laws; limited by text, precedent, and appointments by the other branches)

- Federalism (national handles truly national things; states & localities handle the rest)

- Bill of Rights (bright red “Do Not Cross” lines)

In short: enough power to govern, never enough to rule you like a subject.

How We Lost Focus

Over time, emergencies and convenience stretched the locks:

- Perma-crisis government: Wars, recessions, pandemics—“temporary” powers become habits.

- Party machines & national media: Politics centralizes; local institutions weaken.

- Administrative sprawl: Agencies write detailed rules; accountability blurs.

- One-size funding strings: Distant grants tell locals what to do.

- Digital chokepoints: A few platforms influence speech, trade, and reputation—rules by Terms of Service, not by town hall.

No single villain—just slow drift. The result: power stacks up where the few can steer the many.

The Locks We Need Now (Plain and Practical)

A. Keep decisions close to the people they bind

- Use home rule by default for schools, streets, land use, and small business.

- Let state/federal step in only for real spillovers (rivers, air, interstate fraud).

- When they do step in, keep local revenue and choice of methods.

B. Limit “emergency” shortcuts

- Put sunset dates on emergency orders and big delegations of power.

- Require public hearings and plain-English impact notes before major rules take effect.

C. Make laws simple and visible

- Single-subject bills (no thousand-page grab bags).

- Recorded votes and who-wrote-this disclosures.

D. Revive face-to-face selection

- More caucus-style local meetings where neighbors debate and decide.

- Open processes that reward character and competence over TV theatrics.

E. Neutral “rails” for digital life

- For core functions (payments, identity, basic speech carriage), require due process and portability so no single gatekeeper can silently banish you from modern life.

F. Budget where we live

- Shift a fair slice of dollars to city/ward budgets with participatory choices—visible projects in months, not years.

A 60-Second Civic Checklist

Before you support a policy, ask:

- Power test: If the worst person had this power, could they abuse it?

- Scope test: Is this problem truly national, or best solved locally?

- Sunlight test: Is the rule short, readable, and traceable to a named decider?

- Sunset test: Does it expire unless renewed in public?

- Swap test: Would I accept this same tool in my opponent’s hands?

If any answer worries you, redesign the lock before you hand over the key.

Why This Matters (for non-lawyers)

Good government isn’t magic—it’s good plumbing. Valves, shut-offs, separate lines, clear labels. When something leaks, you know which knob to turn and who installed it. That’s what written constitutions, local control, and simple laws do: they make power traceable and fixable.

We don’t need to reinvent America. We need to remember what it was designed to prevent—and restore the locks that keep freedom safe from our worst days and our worst leaders.

Design for the worst.

Empower the best.

Keep the keys divided.

That’s how a free people stay free.