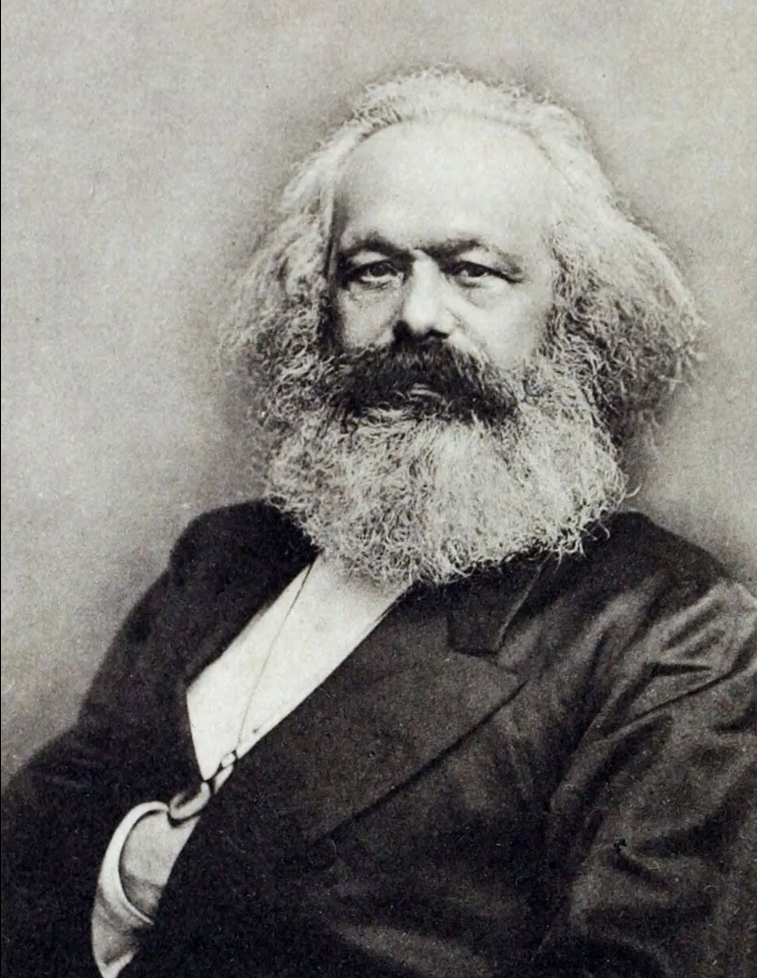

Marxism, as a formal ideology, originated in the 19th century with the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marxism has undergone significant transformations from its inception in the 19th century to the present day. These changes reflect shifts in the global political landscape, economic conditions, and interpretations of Marx’s ideas by various movements and governments. Below is an outline of how Marxism has evolved over time:

1. Origins of Marxism (19th Century)

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels formulated the core ideas of Marxism in the mid-19th century, primarily in works such as The Communist Manifesto (1848) and Das Kapital (1867). Their theory centered around the following principles:

- Historical Materialism: Marx argued that history is driven by material conditions and class struggles, primarily between the bourgeoisie (owners of the means of production) and the proletariat (working class). According to Marx, the capitalist system inherently exploits workers, leading to class conflict.

- Dialectical Materialism: Marx adopted a dialectical approach to understanding history, where contradictions within society (mainly between the classes) lead to revolutionary change.

- Class Struggle and Revolution: Marx believed that capitalism would eventually reach a crisis point due to its internal contradictions, resulting in a proletarian revolution. The working class would overthrow the capitalist class, leading to the establishment of a classless, stateless, communist society.

- Communism as the End Goal: Marx envisioned a society where the means of production would be communally owned, and wealth would be distributed based on need. The state would eventually “wither away” as class distinctions disappeared.

At its core, early Marxism was a critique of capitalism and a call for revolution to establish a more just and equal society.

2. Marxism in the Early 20th Century: Leninism and the Russian Revolution

The 20th century saw the first major transformation of Marxism with the rise of Leninism, which adapted Marx’s ideas to the conditions of Russia.

- Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924): Lenin modified Marx’s ideas to fit Russia’s specific circumstances, where capitalism was less developed than in Western Europe. Lenin argued that a vanguard party of professional revolutionaries was necessary to lead the working class to revolution, as spontaneous class consciousness would not be enough to overthrow the ruling class. This became the basis for the Russian Revolution of 1917.

- State and Revolution: Lenin also revised Marx’s vision of the “withering away” of the state. He believed that after the revolution, the state would be necessary to suppress the remnants of the bourgeoisie and manage the transition to socialism. This led to the establishment of a one-party system in the Soviet Union, a key divergence from Marx’s more democratic vision of post-revolutionary society.

- Democratic Centralism: Lenin’s model of governance, in which the party would make decisions centrally but implement them with discipline, became a core feature of Marxism-Leninism.

After the Russian Revolution, the Soviet Union became the first state to implement Marxist ideas, though in a form significantly different from Marx’s original vision. The establishment of a strong centralized state under Lenin and later Joseph Stalin marked a key change in the definition of Marxism.

3. Stalinism and Marxism in the Mid-20th Century

Joseph Stalin further altered Marxism, leading to what is often referred to as Stalinism:

- Centralized Control and Authoritarianism: Under Stalin, Marxism was adapted to justify a highly centralized and authoritarian state. While Marx and Lenin envisioned the state as a temporary institution in the transition to communism, Stalin used the state apparatus to maintain strict control over the economy, society, and political life.

- Planned Economy: Stalin implemented central planning in the Soviet Union, with the state controlling all aspects of production and distribution. This was a departure from Marx’s idea of communal ownership managed by the workers themselves.

- Repression and Purges: Stalin’s regime was marked by widespread repression, including purges of perceived enemies within the Communist Party, forced collectivization, and the use of secret police to maintain power.

- Socialism in One Country: While Marx and Lenin emphasized international revolution, Stalin promoted the idea that socialism could be built in one country (the Soviet Union) without needing global revolution.

Stalinism deeply influenced Marxist movements worldwide, especially in the socialist states of Eastern Europe and China, but it also led to significant disillusionment among many Marxists, particularly in the West.

4. Maoism and Marxism in the Developing World

In the mid-20th century, Mao Zedong adapted Marxism to the conditions of rural China, resulting in Maoism:

- Peasantry as the Revolutionary Class: Unlike Marx and Lenin, who focused on the urban working class as the revolutionary agent, Mao emphasized the role of the peasantry in revolutionary struggle. This was due to the agrarian nature of Chinese society.

- Protracted People’s War: Mao advocated for a prolonged guerrilla war to defeat the ruling class, as opposed to the rapid urban insurrection envisioned by Marx and Lenin.

- Cultural Revolution: Mao’s belief in the need for continuous revolution to combat counter-revolutionary forces within socialist society led to the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), which aimed to purge capitalist elements from the Chinese Communist Party.

Maoism influenced revolutionary movements in other developing countries, particularly in places like Vietnam, Cambodia, and Peru.

5. Western Marxism and Neo-Marxism (Mid-20th Century to Present)

In the West, particularly after World War II, Marxism evolved into various intellectual currents known as Western Marxism and Neo-Marxism:

- Frankfurt School and Critical Theory: Thinkers like Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse developed critical theory, which sought to explain why the working class in advanced capitalist societies had not revolted as Marx predicted. They focused on how culture, ideology, and mass media reinforce capitalist power structures and control public consciousness.

- Antonio Gramsci: Gramsci introduced the concept of cultural hegemony, suggesting that ruling classes maintain power not only through economic control but also through control of ideas, beliefs, and cultural institutions. He argued for the importance of winning cultural battles as a prelude to political revolution.

- New Left: In the 1960s and 1970s, the New Left emerged in Europe and the U.S., blending Marxism with issues like civil rights, feminism, environmentalism, and opposition to war. These movements emphasized not only economic class struggle but also the liberation of marginalized groups.

- Post-Colonial Marxism: Marxist ideas were adapted by thinkers like Frantz Fanon and Amílcar Cabral to critique imperialism and colonialism, arguing that the global capitalist system relied on the exploitation of the Global South.

6. Contemporary Marxism

Today, Marxism remains a vibrant intellectual and political tradition, though it has splintered into many different strands:

- Ecological Marxism: Some Marxists have incorporated environmental concerns into their critique of capitalism, arguing that the capitalist mode of production is inherently unsustainable and destructive to the environment.

- Digital Marxism: With the rise of the digital economy, some contemporary Marxists are examining how platforms like Amazon, Google, and Facebook represent new forms of capitalist exploitation and surveillance.

- Global Marxism: Modern Marxists often focus on global capitalism, addressing issues of inequality, labor exploitation, and imperialism in the context of a highly interconnected world economy.

The definition of Marxism has shifted considerably from its 19th-century roots to the modern era. What began as a critique of capitalism and a call for proletarian revolution has been adapted by Leninism, Stalinism, Maoism, and various intellectual movements in response to different historical and political contexts. While the core of Marxist thought remains a critique of capitalism and the advocacy for a classless society, its modern interpretations are far more diverse, addressing issues of culture, environment, globalization, and social justice.