“Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.” – Thomas Jefferson

Vigilance, as Jefferson warned, is not a mood; it’s a civic discipline. In a town that thrives on framing, selective leaks, and attention management, the first thing captured is not a vote—it’s your time and your sense of proportion. House of Cards teaches this by refusing to flatter us with heroes; it makes us earn clarity. If we don’t learn to see how incentives shape behavior, the Overton window will move while we’re busy arguing about the window dressings. The show’s cool indifference is the tell: power inches forward by normalizing yesterday’s “unthinkable” as today’s “necessary.” That’s the slow work of drift—committee by committee, crisis by crisis—until the new normal is simply “how it’s done.”

This is where the Hegelian dialectic—problem, reaction, solution—shows up as political craft, not philosophy seminar. A shortage becomes panic, panic becomes pressure, pressure becomes a pre-written package “to restore stability.” We applaud the fix while the price of the fix (new authorities, new surveillance, new dependencies) becomes the real policy. Frank’s world makes this visible: the public spectacle is the reaction; the closed-door markup is the solution that was waiting all along. If we don’t name the pattern, we’ll keep mistaking performance for reality and consent for capture.

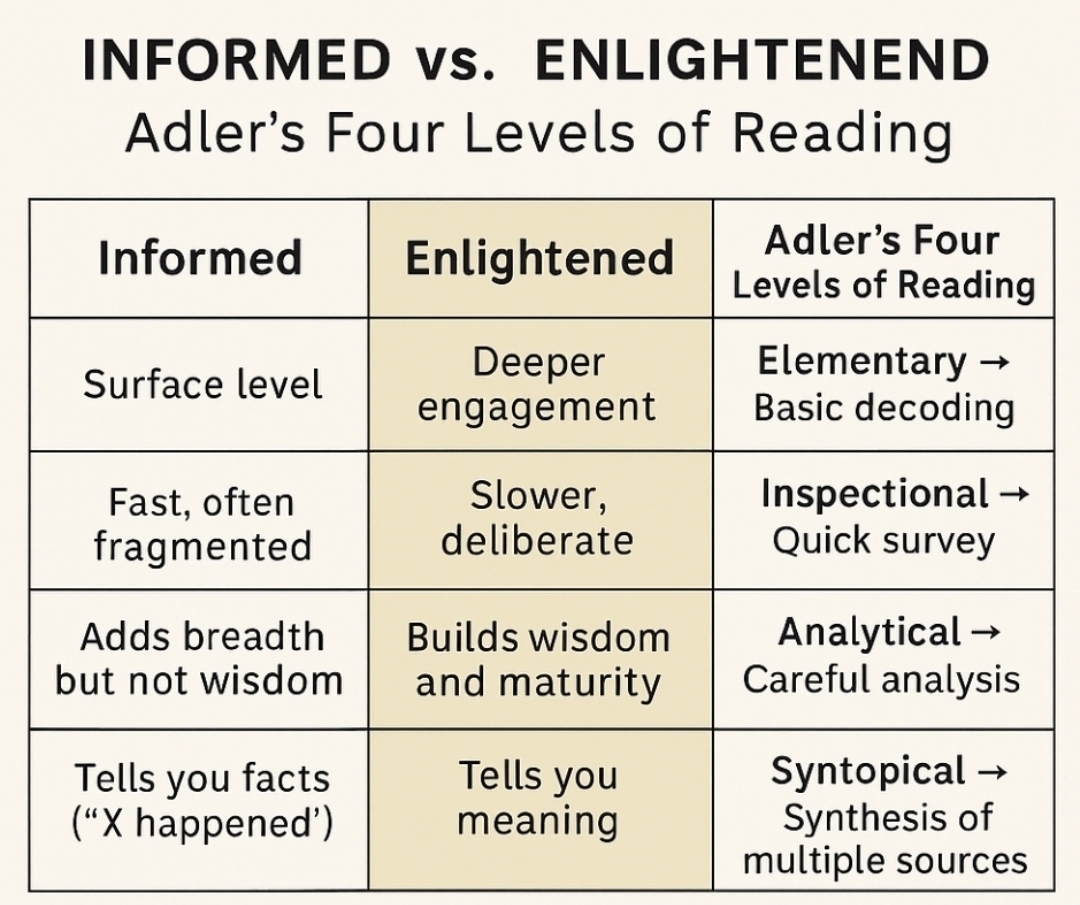

That’s why we need to “read” moving images at four levels. Level 1: Literal—what happens (plot, who wins the vote). Level 2: Interpretive—what it means (motives, trade-offs, who owed whom). Level 3: Analytical—how it works (which incentives, procedures, and gatekeepers made it possible). Level 4: Syntopical—what it reveals across works and real life (how this episode rhymes with your two-party show thesis, lobbying case studies, or last year’s “emergency” bill). Watch once for the story; rewatch for the machinery. The first viewing entertains; the second instructs; the third immunizes.

And remember the old dramaturgical rule often called Chekhov’s gun: if a gun appears in Act I, it will fire by Act III. Translate that to politics: if a “temporary” power appears in a crisis, expect it to be used (and expanded) later. If a character introduces a dependency—an off-ledger donor, a kompromat file, a “public-private partnership”—assume it’s not set dressing; it’s the device that will drive the third-act turn. House of Cards plants these props in plain sight. The lesson isn’t paranoia; it’s pattern recognition.

Media, the dominant technology of programming, reinforces those patterns by deciding which acts we see and which we don’t. Frank’s partnership with Zoe isn’t just about scoops; it’s about surface area—how much of the real fight ever reaches the audience. When media coverage shrinks the map to podium soundbites and horse-race polls, we lose the committee room, the enforcement memo, the consent decree, the rulemaking—where the true plot resolves. Diversifying inputs isn’t a lifestyle choice; it’s a civic countermeasure against narrative captivity.

So tie this back to Jefferson: vigilance means cultivating the habit of structural noticing. Spot the leverage before you pick a side. Ask who benefits from the framing before you argue the frame. Track the “temporary measure” before it becomes permanent architecture. Do this across stories—your “two-party show,” elite consolidation, NGO gloss over K-Street muscle—and the show’s discomfort becomes useful: it turns spectators into auditors. And auditors, unlike fans, change outcomes.

In short: treat House of Cards as a training film in the language of power. Read it at all four levels. Mark every “gun on the mantle.” Watch the window, not just the drapes. Then carry that discipline into city council, school board, legislature, and newsroom consumption. The documentary is happening; our job is to stop being extras and start being editors.

Premiering in 2013 as Netflix’s first flagship original drama, House of Cards—created by Beau Willimon and adapted from Michael Dobbs’s novel and the 1990 BBC series—arrived just as American politics was hardening into permanent campaign mode. Its cynically elegant portrait of Washington, D.C. (copied and pasted in city, county and state arena) feels enduringly applicable because it doesn’t chase headlines; it dramatizes the mechanics that outlive any news cycle: whip counts and committee leverage, donor dependence, lobbying muscle, media choreography, and the quiet quid pro quo that turns ideology into inventory. In other words, it’s not timely because it predicts events—it’s timely because it captures the incentives that reliably produce them.

You don’t watch House of Cards for realism; you watch it for recognition. Strip away the Shakespearean asides and murdery flourishes and you’re left with a work-instruction manual on how modern power is acquired, laundered, and protected. That’s why the show can feel less like fiction and more like a documentary with better lighting—its characters speak the grammar of real politics: leverage, dependency, deniability, and narrative control.

Below is a brief guide to why Frank Underwood’s Washington maps so uncomfortably onto the world outside your screen—and how it echoes themes you’ve explored in your pieces on the two-party show and elite consolidation.

The Charming Executioner: Frank as an archetype, not a one-to-one

Viewers often compare Frank’s glad-handing pragmatism to well-known operators from both parties—think ’90s triangulation politics on one side and hardball congressional whip counts on the other. The point isn’t to equate Frank with any one real figure; it’s that he embodies an archetype: the politician who treats ideals as bargaining chips, not lodestars. That archetype survives every administration.

Takeaway: The face changes; the method persists.

The Playbook: Quid pro quo as the operating system

Underwood’s world runs on IOUs. Jobs, riders, committee slots, regulatory tweaks—every favor accrues interest. The article “Take Washington DC and Shove It: The Two-Party System—Government Is a Show” argues the “fight” is often performative while the real deals are cut off-camera. The show stages exactly that: public warfare, private back scratching, and the quiet settling of accounts.

Takeaway: Bipartisan “combat” often masks bipartisan commerce.

Kompromat economics: Finding (or manufacturing) leverage

Doug Stamper’s bleak skill set—finding addictions, affairs, escorts, paper cuts to press—is the show’s most unsettlingly believable engine. In the real world, versions of this appear whenever elites cultivate compromise and dependency (think: hush money, opposition research, predatory networks, or entrapment schemes, i.e. the Epstein list being played out). The series condenses a long, sordid tradition into one meticulous fixer.

Caution note: Real scandals differ case by case; not every ugly rumor is true, and not every true thing is prosecutable. But the incentive to obtain leverage—by discovering secrets or creating them—is constant.

Takeaway: Power hoards secrets the way finance hoards yield.

Narrative capture: When media is both stage and prop

Frank weaponizes Zoe Barnes not just for leaks but for story framing—timing, emphasis, and villains. In real life, a handful of conglomerates control much of the news and entertainment pipeline. That doesn’t mean a single mastermind dictates coverage; it means incentives—access, advertising, regulation, and relationships—rhythm the newsroom. Your note that “the press works with politicians and oligarchs” tracks with a simpler truth: when careers and profits depend on access, accountability competes with proximity.

Takeaway: Control the narrative surface area, and policy fights start uphill for your opponents.

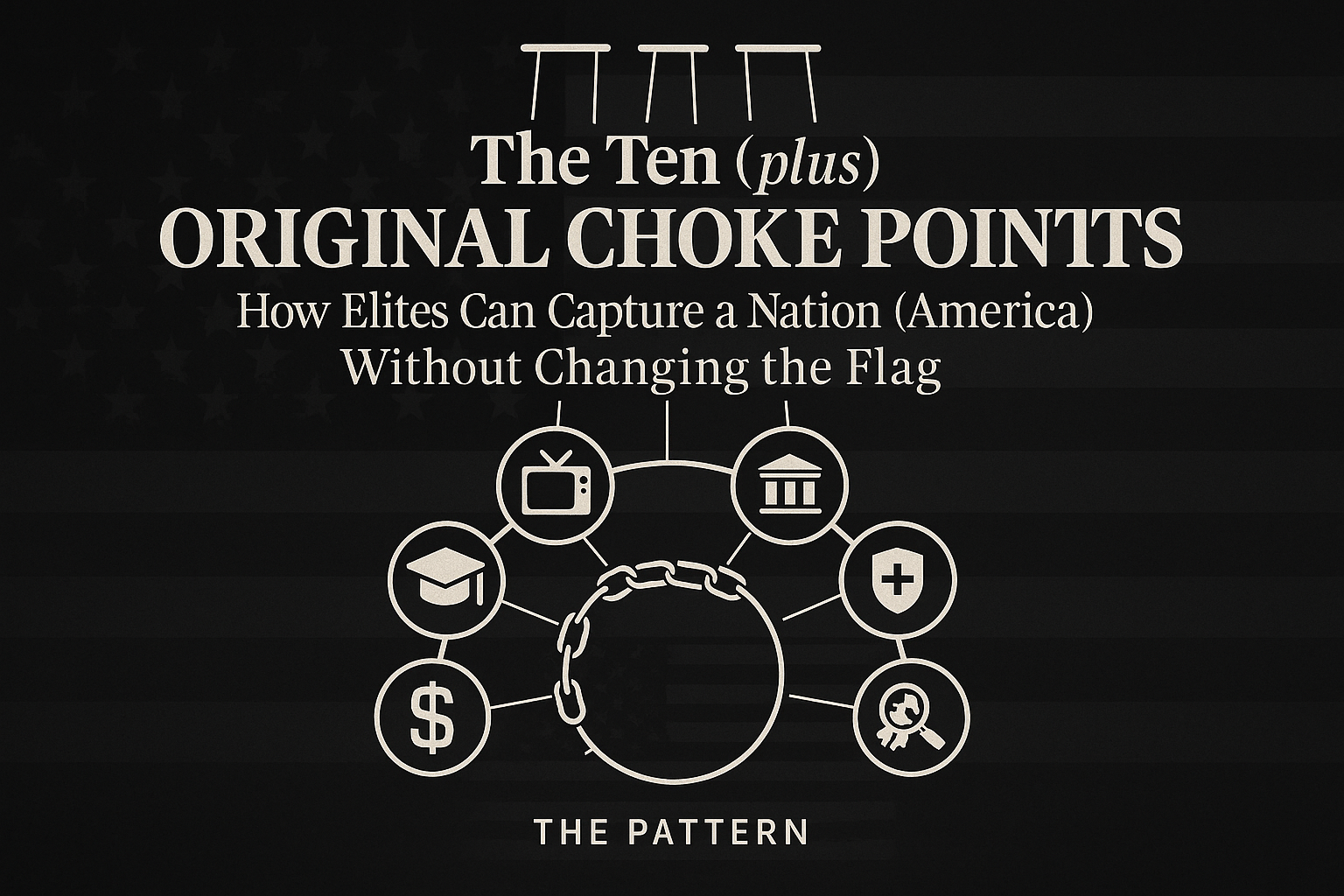

NGOs & lobbyists: White-glove and bare-knuckle, working in tandem

Claire’s NGO and Remy Danton’s lobbying shop illustrate two flanks of the same campaign: moral language (public good, humanitarian need) and instrumental muscle (votes, money, regulatory carve-outs). Your “Coexistence and Commerce” piece argues money consolidates over time; the show dramatizes how consolidation buys policy velocity—through foundations, consultancies, and “public-private partnerships” that sound benevolent but often steer outcomes.

Takeaway: Influence wears many uniforms—charity gala black-tie and K-Street cufflinks.

The bipartisan theater: Rivals at the podium, partners in the cloakroom

House of Cards doesn’t say “both sides are the same.” It says: both sides need each other. They trade procedural weapons, rotate villains for the nightly news, and keep the appropriations river flowing. The audience gets moral clarity, the players get budget lines. Your “two-party show” thesis appears in miniature whenever sworn enemies co-sponsor a loophole.

Takeaway: Public polarity can coexist with private collusion.

Money’s endgame: From donors to deciders

Frank’s duel with billionaire Raymond Tusk is a tutorial in policy as portfolio risk. Nuclear fuel supply chains, tariffs, and blind trusts matter more than speeches because cash flow is the true constituency. Across history, wealth tends to pool, then govern—directly or by proxy. The series turns that macro trend into a personal feud, but the underlying logic holds: capital seeks capture (of regulators, committees, and crises).

Takeaway: When money concentrates, politics intermediates rather than restrains.

Why it feels like a documentary

- The behaviors are real: carrot-and-stick, narrative shaping, vote whipping, donor service.

- The stakes are real: contracts, wars, nominations, markets.

- The aesthetics are fictional: the bodies and the monologues.

The result is a TV mirror that’s closer to verisimilitude than verity—recognizable enough to sting.

How to watch—and what to do with the discomfort

- Spot the leverage. Whenever a character changes course, ask: What IOU just got called in?

- Follow the incentives. Who gains money, access, or cover if this narrative wins?

- Disaggregate the theater. Separate podium fights from committee markups and rulemakings.

- Audit the intermediaries. Which lobbyists, NGOs, law firms, and “task forces” quietly glue deals together?

- Diversify your media diet. If a small number of owners set most front pages, you need orthogonal sources to triangulate truth.

The uncomfortable conclusion

House of Cards resonates not because it’s accurate in its particulars, but because it’s honest about incentives. It shows politics as transactional systems dressed in moral claims, where leverage is king, secrecy is currency, and the show must go on—red tie, blue tie, same green room.

If that feels like a documentary, it’s because the documentary is happening, every day, in committee rooms, hotel suites, and inboxes you’ll never see. The question isn’t whether the game exists. It’s whether more of us can learn to see it, name it, and interrupt it.