The core claim (in one line)

American mass schooling isn’t primarily designed to educate free people; it’s a management system that conditions obedience, dependency, and consumption—and the mechanisms that do this (standards, tests, age-grading, bells, seat-time, credentials) are the “weapons” in the title.

What Gatto says the system really teaches

Gatto reprises and extends his “hidden curriculum” critique. Regardless of subject labels, the machinery of school imparts these habits:

- Confusion by design: Sliced-up periods, bell interruptions, and textbook snippets block coherent understanding and deep focus.

- Class position: Tracking, labels, and “levels” tell children where they belong.

- Indifference: Nothing matters for long; the bell guarantees it.

- Emotional/intellectual dependency: Authority decides what’s important and when you’re “ready.”

- Provisional self-esteem: Worth comes from grades, prizes, and external approval.

- Constant surveillance: Privacy is suspect; compliance becomes reflex.

He argues these aren’t accidents. They’re structural features of a model meant to produce predictable, compliant adults.

The architecture of control (the “weapons”)

Gatto walks through the parts of school that do the heavy lifting for social control:

- Compulsory attendance + age-grading

- Keeps youth segregated from adult life where real competence forms.

- Industrial “batching” replaces mentorship and mixed-age learning.

- Seat-time (Carnegie Units) and bell schedules

- Time served becomes the currency of “education,” not mastery.

- Interrupts concentration so real expertise is hard to build.

- Standardized testing

- A sorting tool masquerading as science.

- Narrows curriculum, incentivizes gaming and compliance, brands children early, and legitimizes tracking.

- Credentialism

- Paper proves “readiness” even when skill is absent; competence without credentials is ignored.

- Extends adolescence and delays responsibility.

- Textbooks & scripted pedagogy

- Pre-digested “content” displaces living books, direct experience, and original sources.

- Teachers become delivery techs; students become passive receivers.

Where he says this came from (the genealogy)

- Prussian roots: 19th-century admiration for the Prussian model (centralized, compulsory, age-graded) imported a system that prized order and uniformity over independence.

- Social-efficiency era: Early 20th-century administrators and psychologists reframed schooling as workforce sorting.

- Foundation steering: Large philanthropies (Rockefeller, Carnegie, Ford) funded teacher colleges, testing, and “model” reforms that normalized central control and measurement.

- Testing/eugenics pipeline: Intelligence testing became the “scientific” aura for ranking, tracking, and limiting horizons.

What this produces (the downstream effects)

- Shallow literacy & numeracy (just enough to consume, not to self-educate).

- Learned helplessness (needing rubrics and permission to begin).

- Civic amnesia (little history, rhetoric, or practice in self-government).

- Economic docility (accepting low-autonomy roles; confusing brand fluency with knowledge).

Gatto’s evidence style

- Insider’s view: He taught in NYC for nearly 30 years (and won major teaching awards). Much of the book is case-based: what happened when he suspended the machinery—ditched grades for narrative feedback, brokered apprenticeships, created student-run publications and businesses, allowed long reading/writing projects—and watched motivation explode.

- Mini-biographies of autodidacts: Franklin, Edison, Lincoln, Nightingale, Twain, and others as proof that self-directed, mentor-rich learning builds capability.

- Administrative history: Memos, policies, and reform literature showing an explicit drive toward social efficiency and measurement.

The sharpest chapters/ideas (what he most wants you to remember)

1) School is not education

He hammers the difference: education grows from purpose, mentors, mastery, and service; schooling is institutional routine. Confusing them lets the routine masquerade as learning.

2) Testing is the keystone

Standardized tests feel neutral; he argues they are the central weapon: they license narrowing, justify tracking, and convert curiosity into performance anxiety. They also produce data capital that keeps the apparatus running.

3) The “Bartleby Project”

Gatto’s civil-resistance proposal: students (backed by families) politely refuse standardized tests—“I prefer not to”—and short-circuit the data stream that powers compliance. (He’s explicit about legality and civility; the point is starve the system’s key metric.)

4) How elite schooling really differs

Top prep schools, he says, don’t just cram content; they cultivate habits of power:

- Confidence with adults; rhetoric, writing, languages

- Independent projects and public exhibition of work

- Networks and mentorships

- Manners, time management, courage, and responsibility

He argues every child can develop these—if time and structure change.

5) Boredom is a signal, not a flaw in kids

When teachers say students are “bored,” he flips it: the structure makes boredom rational. Change the structure—long blocks, real problems, audience and stakes—and attention returns.

What he recommends (practical alternatives)

For families

- Reclaim time: Cut back on screens/homework busywork; protect multi-hour blocks for reading, building, gardening, music, tinkering.

- Mentors & apprenticeships: Each teen should do real work that serves someone outside the family; rotate across crafts, trades, and professions.

- Library first, textbooks last: Read whole books; use primary sources; write and speak about them.

- Portfolio over GPA: Collect artifacts—essays, projects, businesses, performances—and present them publicly.

For teachers (inside the system)

- Long projects & public exhibition: Replace unit tests with products for real audiences.

- Mixed-age and cross-discipline work: Collapse silos whenever you can; let older students teach younger.

- Narrative evaluation: Replace points with descriptive feedback and conferences.

- Community mapping: Treat the town as campus—courts, shops, farms, labs, museums, city hall.

For policy/citizens

- End high-stakes testing & seat-time mandates.

- Fund learners, not systems (direct scholarships/vouchers/ESA models with broad autonomy).

- Legalize/expand apprenticeships, microschools, and part-time attendance.

- Decouple credentials from opportunity (hire for portfolios and trials, not just diplomas).

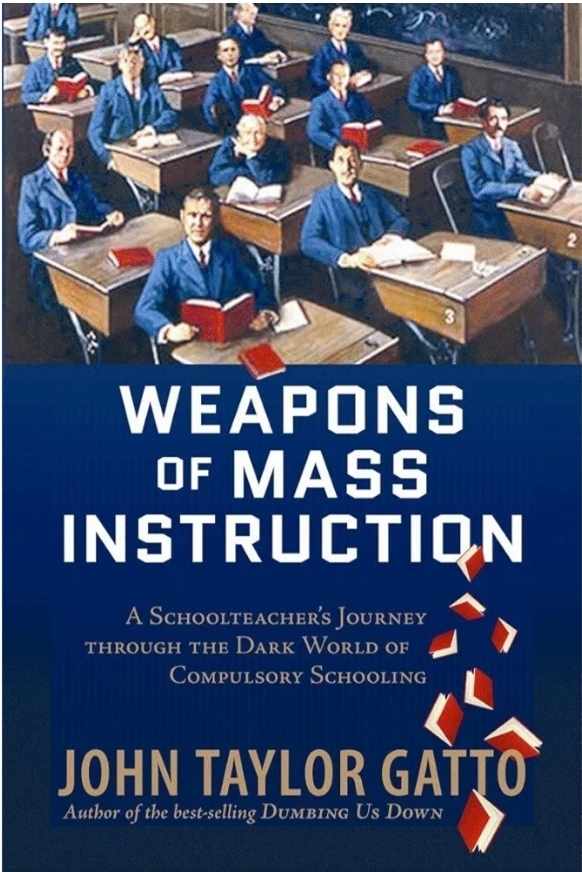

How this book differs from Gatto’s other works

- Dumbing Us Down is the concise moral indictment (his “seven lessons”).

- Underground History is the archival deep dive into origins and power.

- Weapons of Mass Instruction blends both, but it’s more tactical: memoir snapshots of classroom subversion, profiles of self-taught lives, and a call for civil resistance (the Bartleby Project) plus a concrete menu of what learning can look like tomorrow morning.

Anticipating common pushbacks

- “Isn’t this too conspiratorial?” Gatto cites explicit policy aims (social efficiency/testing) and shows how structure drives behavior; you don’t need a secret plot for perverse incentives to accumulate.

- “What about equity?” He argues the current system pretends equity while entrenching caste via labels and tracks; opening time, mentors, and public demonstration of mastery is more equitable than one-shot tests.

- “What about college?” He urges building portfolios, references, and real work; many selective programs now read for this, and multiple non-college paths can be honorable and prosperous.

A compact checklist to act on his ideas

- Replace two nights of homework a week with family seminar: one great essay/speech, read aloud and discussed.

- Help your teen cold-email five adults to shadow.

- Start a mixed-age makers’ night with neighbors; end each month with a public show-and-tell.

- Swap one textbook per course for a pair of whole books (classic + modern counterpoint).

- Build a yearly portfolio site (writing, builds, talks, service).

- If you share his stance on testing, explore your state’s opt-out policies and the civic/ethical implications before you act.

Bottom line: In Weapons of Mass Instruction, Gatto argues that the routines of compulsory, standardized, age-graded schooling are deliberate tools that train obedience and dependency. He shows, from the inside, that when you remove those routines and add purpose, mentors, and audience, students wake up fast. His warning is civic: a nation habituated to bells, grades, and surveillance can’t long remain free. His remedy is practical: reclaim time, mentors, mastery, and public responsibility—and starve the mechanisms that reduce education to measurement.