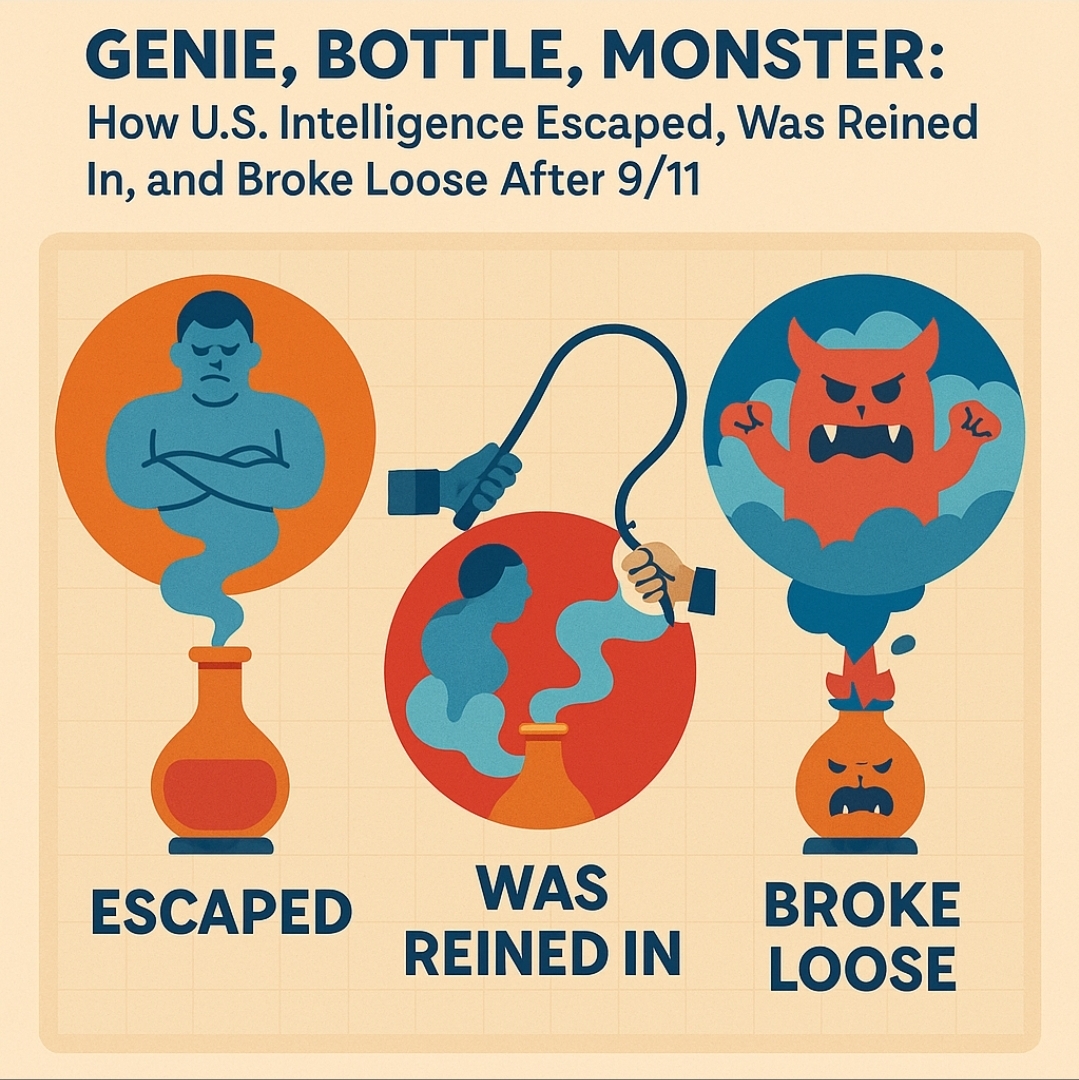

When President Harry Truman reflected on the creation of the CIA a month after President Kennedy’s assassination, his words carried the weight of regret. He had envisioned a quiet intelligence-gathering agency—a disciplined “eyes and ears” for America’s elected leaders. Instead, what emerged was a global, unaccountable power center. In his own words, the CIA had become an “operational and policy-making arm of the government,” steering national direction from the shadows. That unease was not paranoia—it was prescience. Truman’s warning foreshadowed the rise of a parallel government, one capable of manipulating presidents, rewriting history, and burying truth under secrecy.

The Church Committee of 1975 briefly pulled the curtain back. Despite being smeared as “KGB sympathizers” by the establishment they threatened, Senator Frank Church and his team exposed a hidden empire within the republic—covert wars, domestic surveillance, assassinations, and media infiltration. They tried to put the genie back in the bottle with oversight, transparency, and constitutional limits. But the bottle was already cracking.

Then came 9/11, and with it, the monster Truman had feared. Under the banner of security, the intelligence community reclaimed and multiplied the powers the Church Committee once restrained. The Patriot Act, warrantless surveillance, secret kill lists, and “wars of preemption” were sold as patriotism but functioned as institutional consolidation—a coup in slow motion. The same apparatus that once spied on citizens now spies on the entire planet. The same shadow nexus that led us into Iraq now binds U.S. foreign policy to Israel’s regional ambitions, ensuring that perpetual war remains “business as usual.”

If the original Church Committee represented a moment of moral clarity, what we need now is Church Committee 2.0—a modern inquest into this deep state leviathan that undermines the Constitution it claims to defend. The republic cannot coexist with a government that operates above it, immune from accountability and driven by global interests. To remain free, America must once again confront the monster it created—and this time, seal the bottle for good.

______________________________________________

Is the “deep state” real? Strip away the slogans and you find something simpler and more disquieting: a durable, unelected national-security apparatus that outlasts presidents, operates largely in secret, and—at times—pushes past the boundaries set by law and voters. It wasn’t born as a conspiracy. It was built for war.

World War II was the catalyst. Franklin Roosevelt empowered “Wild Bill” Donovan to create the OSS, a do-what-it-takes intelligence shop that ran sabotage, disinformation, front companies, and paramilitary ops. When the war ended, Harry Truman shut the OSS, warning against any “American Gestapo.” But the Cold War arrived almost immediately. Fear of the Soviet Union led Truman to sign the 1947 National Security Act, creating the CIA with a deliberately vague mandate to perform “other functions and duties” tied to national security—a euphemism everyone understood to include covert action.

What followed was a two-decade surge of secret power. Intelligence chiefs—many of them literal Georgetown neighbors—helped tilt foreign elections, backed coups in Iran and Guatemala (among others), and green-lit programs like MKUltra at home. The FBI’s COINTELPRO and the CIA’s CHAOS surveilled and harassed Americans—from civil-rights leaders to anti-war activists—while senior officials amassed personal dossiers that doubled as leverage on Congress and the White House. Even Truman, who created the CIA, later warned that the agency had cast a shadow over America’s reputation.

The backlash came in the 1970s. The Senate’s Church Committee dragged poison-dart guns, assassination talk, domestic spying, media infiltration, and non-consensual drugging into the light. Out of that sunlight came new oversight committees, reporting rules, and legal fences around domestic surveillance. For a time, the genie was—if not caged—at least back in the bottle.

Then 9/11 uncorked it. The Patriot Act passed; budgets ballooned; new buildings and programs proliferated; and old lines blurred. The security state revived and scaled practices the 1970s had curbed: warrantless collection, secret watchlists, black sites, and “enhanced interrogation.” Presidents who promised to rein it in discovered how little leverage they had over a sprawling, classified ecosystem. Edward Snowden’s disclosures merely confirmed what growth in headcount and concrete had already signaled: America had reconstructed a semi-autonomous security branch that operates outside the founders’ neat triangle unless Congress and the courts actively pull it back.

So yes, something real exists behind the “deep state” label. Not a cartoon conspiracy, but a war-built machine that became a standing feature of American life; one we briefly disciplined—and then, in a panic, let loose again. The question isn’t whether it’s there. It’s whether a republic can keep it on a leash.

The Night the President Went to a Cocktail Party

During the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962—after a U-2 spy plane photographed canvas tents and launch gear hiding Soviet nuclear missiles just 103 miles from Florida—John F. Kennedy faced a roomful of hawks urging an invasion of Cuba. That evening, instead of staying in the Situation Room, he kept a dinner date in Georgetown at columnist Joe Alsop’s house. It wasn’t escapism. It was proximity to power.

On those tree-lined blocks lived the men who, in practice, shaped the hardest calls of the Cold War: Allen Dulles (longest-serving CIA director), Frank Wisner (OSS/CIA founder), William Colby (future CIA director), Chip Bohlen (former ambassador to the USSR), and Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter. Kennedy himself kept a home nearby. This “Georgetown set”—many of them veterans of the OSS who joked their agency was “Oh-So-Social”—used salons and supper tables as informal command posts. Files were kept in safes, but decisions often congealed over drinks.

That night crystallizes a larger truth: alongside the visible machinery of constitutional government sat an unelected, secretive network with real leverage over outcomes—people who didn’t face voters, yet trafficked in the information, relationships, and covert tools that presidents needed in a pinch. It wasn’t a movie-villain cabal; it was a war-forged social graph that made the capital run when events turned kinetic.

The arrangement had virtues and risks. On the plus side, it offered presidents a fast, trusted backchannel of experience when formal bureaucracies were slow or fractious. On the minus side, the same intimacy could blur lines of accountability. As later decades showed, the intelligence world’s Georgetown culture could slide from counsel to control—amassing dossiers, nudging policy in the shadows, and assuming a freedom of action the framers never contemplated.

Kennedy’s walk to that party, on the eve of possible nuclear war, is a snapshot of how Washington actually worked—and still often works—when secrets and crisis compress decision-making into small rooms. It’s not a Q-shaped plot. It’s the social reality of a national-security state that grew up in wartime and learned to govern, in part, after hours.

Blackmail as leverage

That Georgetown ecosystem overlapped with J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI and James Angleton’s counterintelligence shop—offices known to keep compromising files on public figures. JFK understood the cost of tangling with Hoover; it’s a big reason Hoover remained untouchable. Everyone understood the basic physics: the people who held the secrets held the leverage (Can we say Epstein files). This wasn’t movie-style conspiracy so much as ambient leverage: everyone knew who knew what.

By the late 1960s and into the 1970s, the national-security apparatus had become a powerful, well-funded machine running covert programs around the world—and it used information asymmetry at home to keep prying hands off the controls. Former officials and investigators describe a climate in which:

- Compromising intel was a tool. Angleton could rattle off private details to remind visitors what the CIA could hear—down to repeating what one man had said to his wife in bed the night before. Hoover’s FBI kept exhaustive dossiers on public figures (including sexual and financial vulnerabilities) and made sure the targets knew it.

- Untouchables stayed untouchable. John F. Kennedy understood the cost of crossing Hoover. The knowledge that Hoover possessed material on his personal life was a large part of why the FBI director remained in place for decades. This wasn’t a Hollywood cabal so much as ambient leverage: people in power “knew who knew what,” and acted accordingly.

- Oversight was chilled before it began. As the CIA’s covert action portfolio grew (Italy, Iran, Guatemala, Congo, Chile, etc.), senior lawmakers often waved through black-box budgets and avoided specifics. Intelligence veterans recount a routine in which agency heads presented a top-line number and committee chairs replied, in effect, “You’ve got it—and please don’t tell us the details.” When a handful of members did push for investigations, the message from the security services was clear: we have files, and we use them.

- Domestic programs blurred into politics. FBI COINTELPRO and CIA Operation CHAOS targeted anti-war and civil-rights movements; the same collection systems that harvested foreign intelligence created domestic dossiers with political bite. Even when internal reviews concluded the protests weren’t foreign-controlled, the surveillance continued—expanding the inventory of sensitive information on Americans.

This is the darker subtext of the era: you don’t need explicit threats when everyone understands the latent power of secrets. The Church Committee finally dragged much of this into daylight, showing how secrecy plus discretion can morph into soft coercion—blackmail by implication—strong enough to discourage Congress from doing the job the Constitution requires.

What the Cocktail Party reveals

- Two Washingtons: the constitutional city (Capitol, West Wing, hearings) and the intimate city (townhouses, salons, backchannels). In crises, the second often frames the first.

- The seed of “deep state” talk: Not a secret cabal running everything, but a durable, unelected network—intelligence, diplomatic, legal, media—capable of outlasting presidents and constraining the menu of choices.

- Why oversight later mattered: The Church Committee’s insistence on sunlight and guardrails was aimed at this very dynamic—limiting the ability of small rooms to decide big things off the books.

The cocktail party is more than a colorful anecdote. It’s a window into how, at the peak of the Cold War, social capital plus secret power formed a parallel decision-sphere—one that didn’t replace constitutional government, but regularly pre-shaped it.

From Wartime Tool to Permanent Fixture

Before World War II, U.S. spycraft was a pop-up shop: build an agency in wartime, tear it down in peace. Pearl Harbor ended that rhythm. Franklin Roosevelt deputized Wall Street lawyer William “Wild Bill” Donovan to create the Office of Strategic Services (OSS)—a centralized, anything-that-works outfit. The OSS ran sabotage teams and front companies, forged radio broadcasts, recruited bankers and movie directors, and even green-lighted oddball schemes (bat bombs, psychological ops) if they might rattle the Axis. Its operators met in Georgetown parlors and Manhattan clubs, earning the nickname “Oh-So-Social.”

When victory came, Harry Truman pulled the plug. He dissolved the OSS in 1945 and warned against birthing an “American Gestapo.” A permanent secret police was exactly what the U.S. had just helped defeat.

Then the geopolitical weather flipped. As the alliance with Moscow curdled into the Cold War, Truman’s caution met a new fear: an ideologically driven rival with global reach. Intelligence veterans from the OSS—many living within blocks of each other in Georgetown—pressed to resurrect a peacetime service. In 1947, Truman signed the National Security Act, creating the National Security Council and, crucially, the Central Intelligence Agency.

The CIA’s charter was intentionally elastic. It tasked the agency with “correlating and evaluating” intelligence—and performing “other functions and duties related to intelligence affecting the national security.” Everyone understood the euphemism. “Other functions” meant covert action: influencing elections, running clandestine networks, supporting or toppling regimes, and, where ordered, waging shadow war.

With a broad mandate, minimal early oversight, and a Cold War blank check, the wartime tool became a standing fixture—staffed by the same elite networks that had proven so effective in crisis, now operating as a permanent arm of American power.

The Long Shadow: Coups, Coercion, and Secrecy

From the late-1940s through the early-1970s, America’s covert engine ran hot—and often in the dark. What began as “other functions and duties” in the 1947 charter hardened into a playbook:

- Elections and coups. Cash, media ops, and muscle tilted Italy’s 1948 vote; Operation Ajax (Iran, 1953) deposed Mossadegh; PBSUCCESS (Guatemala, 1954) toppled Árbenz amid United Fruit’s lobbying; knock-on meddling followed in Congo, Indonesia, Greece, and Chile (1973).

- Paramilitary fiascos. The Bay of Pigs put plausible deniability above plausibility, with exiles thrown at Cuba while Washington disavowed fingerprints.

- Mind-control experimentation. MKUltra funneled money through universities and front orgs to test drugs and coercive techniques—including dosing people without consent—in search of a “truth serum” and behavioral control.

- Dragnet collection. Programs like SHAMROCK hoovered up international communications; warrantless taps crept from foreign to domestic edges.

- Domestic targets. The FBI’s COINTELPRO and the CIA’s CHAOS tagged civil-rights leaders, feminists, student organizers, and anti-war activists for infiltration, disruption, and discrediting—well beyond any “foreign control” pretext.

The justification was always the same: existential struggle. The Cold War’s “anything goes” logic licensed tactics that bent law and values. Some of the people doing it were earnest patriots; a structure with secrecy and impunity made it easy to slide.

Secrecy enabled more than operations; it enabled leverage. J. Edgar Hoover kept voluminous personal files (including the infamous anonymous letter pressing Martin Luther King Jr. toward despair). CIA counterintelligence chief James Angleton cultivated the aura of omniscience—up to quoting back private conversations to remind visitors who held the wiretaps. Appropriators, meanwhile, rubber-stamped black budgets, often preferring not to know details. The architecture of “trust us” became the norm.

By the early 1970s, the bill came due. The Church Committee pried open the vault: assassination ideas and devices, illegal mail openings, journalist recruiting (Mockingbird), non-consensual drugging, domestic surveillance. The hearings codified what critics had warned—unelected, unaccountable power had grown beyond the constitutional frame. Even Harry Truman, who had created the CIA to coordinate intelligence, wrote soon after JFK’s assassination that the agency had “cast a shadow” over America’s reputation and should be cut back to analysis, not action.

That history isn’t ancient trivia; it’s the template. When fear expands, secrecy spreads; when secrecy spreads, covert capability tends to bleed into covert license—abroad and at home. The lesson of the long shadow is not that intelligence is unnecessary, but that unchecked intelligence becomes something else.

Truman’s Second Thoughts (December 1963)

What he said. A month after President Kennedy was assassinated, Harry S. Truman—the president who signed the 1947 law creating the CIA—published an op-ed in The Washington Post warning that the Agency had drifted far beyond what he intended. He wrote that he never envisioned a peacetime “cloak-and-dagger” arm and that the CIA’s behavior was “casting a shadow” over America’s historic reputation. His prescription: cut the covert activism and return the CIA to intelligence collection and analysis under firm civilian control.

Why it matters. The caution didn’t come from a crank or a partisan foe; it came from the architect of the postwar system. Truman’s public regret is the earliest, clearest statement of the problem this essay traces: mission creep + secrecy = unaccountable power.

Vietnam-era domestic spying & Operation CHAOS

How it started. As the Vietnam War ground on and protests surged, President Johnson pressed the CIA: is a foreign hand behind this? Director Richard Helms tasked counterintelligence chief James Angleton to stand up a domestic program—Operation CHAOS—despite the CIA’s charter barring domestic policing.

Stated mission. Find evidence that the anti-war movement was funded, directed, or materially aided by Moscow, Hanoi, or other foreign services.

What they actually did.

- Built files on U.S. citizens and groups; infiltrated meetings; ran informants and liaison; harvested mail and communications.

- Cross-tapped with other “alphabet” programs:

- FBI COINTELPRO (disruption/neutralization of domestic groups, including civil-rights leaders and feminist activists).

- NSA’s SHAMROCK (bulk collection/warrantless taps flowing to the intelligence community).

- Grew despite negative findings: by ~1970, CHAOS had ~30 officers, hundreds of agents, and a widening target set—students, clergy, journalists, and mainstream anti-war groups.

What they found (and ignored). Repeated internal reports said the obvious: the movement wasn’t foreign-controlled or financed. Foreign adversaries “liked” the protests, but didn’t run them. The program continued anyway. Even CIA insiders balked—some joked they were “spying on our own wives and kids.”

Culture of leverage. Parallel to CHAOS, J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI and Angleton’s shop kept personal dossiers on public figures—compromising details that discouraged oversight. Lawmakers learned not to look too closely.

The break point—Church Committee. By 1975–76, Senator Frank Church dragged all of this into daylight:

- CHAOS’s domestic surveillance (despite the CIA charter).

- COINTELPRO’s targeting of MLK and others (including the infamous “you should do the one thing left” letter).

- MKUltra’s non-consensual drugging and “mind control” experiments.

- Media infiltration and assassination ideas; even the CIA’s silent poison-dart gun was shown on camera.

What changed. Congress created permanent intel committees, imposed reporting and legal fences around domestic spying, and established a norm: classified programs still answer to elected oversight. Agencies hated it; the public largely welcomed it. For a time, the genie was mostly back in the bottle—until the 9/11 attacks prompted a fresh expansion of authorities and budgets, uncorking it again.

The Bottle: Church Committee Sunlight

The Vietnam–Watergate era’s domestic spying finally triggered a democratic immune response. In 1975–76, Senator Frank Church’s hearings hauled secrets into daylight: poison-dart devices and assassination planning, mail-opening and warrantless taps, the FBI’s COINTELPRO against civil-rights and anti-war leaders (including the notorious letter to Dr. King), CIA’s domestic CHAOS files, journalist recruitment, and MKUltra’s non-consensual drugging. Career insiders testified; 10,000+ pages of files surfaced; the public saw how far “national security” had drifted from law.

What changed (the short list):

- Permanent oversight. Congress stood up the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (1976) and the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (1977) to supervise classified programs continuously, not just in crises.

- Assassination ban & executive rules. President Ford’s EO 11905 (reaffirmed and refined by later orders) prohibited political assassination and imposed procedures for covert action and intelligence collection.

- Attorney General guidelines. New DOJ rules (e.g., the Levi Guidelines) narrowed domestic “security” investigations, demanding articulable facts and tighter predication.

- Covert-action findings. Post-Watergate laws (e.g., Hughes–Ryan and later the Intelligence Oversight Act) required a written presidential finding for covert actions and timely notification to Congress.

- Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (1978). FISA created a court process for national-security surveillance and drew a statutory line between foreign intel collection and domestic law enforcement.

- Inspectors General & compliance. Agencies formalized internal watchdogs, general counsel gates, and reporting channels for questionable activities.

Agencies loathed the exposure (“Angleton smears Church as a ‘KGB agent’; Helms rages; Kissinger fumes that U.S. intelligence is being ‘opened up’”); many Americans welcomed the accountability. For a time, the genie went mostly back in the bottle: black budgets still existed, but the default flipped from “don’t ask” to “show your homework to elected overseers.”

9/11: The Monster Unleashed Again

September 11 didn’t invent the “deep state,” but it super-charged it. The shock of the attacks produced a Pearl Harbor–style mindset—anything goes to keep us safe. In practice, that meant:

- Laws and money on tap. Congress raced through sweeping authorities (e.g., the PATRIOT Act), while black budgets ballooned. As Johnny Harris notes, taxpayers funded millions of new top-secret billets and enough classified office space to equal 22 U.S. Capitol buildings. The result was a thicket of new programs—so many oddly named compartments that no single leader could track them all.

- Old lines, redrawn in pencil. Techniques the 1970s curbed reappeared at scale: warrantless electronic collection, sprawling watchlists, black sites, and an interrogation regime that critics—later, the law—classified as torture. Inside the intel world, veterans openly said the post-9/11 ethos revived and expanded earlier “anything goes” practices.

- Classification as gravity. Over-classification became the rule, not the exception. As one insider put it, information is power, and the fewer people who have it, the more power those people hold. That made genuine oversight—by presidents, courts, or Congress—harder by design.

- Presidents meet the machine. Candidates promised to rein it in; presidents discovered how little of it they could actually move. Even as rhetoric shifted, targeted strikes and surveillance architectures grew on their watch. The machinery had its own momentum.

- Snowden’s x-ray. When Edward Snowden revealed NSA bulk-collection programs, the public briefly saw the scale of what had been built—PowerPoints for domestic data flows, secret court orders, global taps—and how far the system had stretched beyond what most citizens imagined.

The uncomfortable trade since 2001 is straightforward: we swap liberty for security, mostly in the dark, and in doing so we recreate a semi-autonomous security branch that sits outside the founders’ elegant checks unless Congress and the courts actively pull it back. After 9/11, that active pullback mostly gave way to deference, money, and mission creep.

The Costs of Permanent Secrecy

Accountability decays.

When nearly everything is stamped too sensitive, power pools around the few who hold the clearances and the keys. In the Cold War and again after 9/11, appropriators rubber-stamped “black” budgets while telling directors, in effect, “don’t tell us the details.” Inside that fog, programs multiply, mistakes get buried, and even presidents find they can’t see (let alone steer) the whole machine. The Church hearings showed how far this can drift; the Snowden files showed how far it drifted again.

Overclassification hoards power.

Classification isn’t just a label; it’s leverage. Directors and counterintelligence chiefs historically kept files that could humble rivals or spook would-be overseers. The more that’s secret, the more selective disclosure becomes a currency—what you show, to whom, and when. Oversight turns from audit to guided tour.

Policy skews.

Give an institution covert tools and a permissive mandate, and covert options rise to the top. The OSS/CIA lineage normalized sabotage, coups, and influence ops abroad; post-9/11 normalized bulk collection, watchlists, black sites, and “enhanced” methods. Each success story becomes a template; each buried failure becomes an unseen warning. Diplomacy and open law enforcement—slower, messier, more accountable—lose inside the interagency knife fight.

Mission creep becomes default.

Programs built for emergencies rarely retire when the emergency ends. Pearl Harbor begat a permanent intel bureaucracy; 9/11 begat a sprawling homeland-security archipelago: millions of clearances, entire cities of offices, and so many compartment names no single leader could track them. Sunsets slip. Structures stay.

Blowback grows in the dark.

Secrecy hides second-order effects until they’re public crises: coups that haunt regions for decades; domestic surveillance that chills speech; clandestine partnerships that later taint allies and America’s standing. Because the record is sealed, lessons are slow to spread and fast to repeat.

The Republic trust erodes.

When the public learns—after the fact—that assassination ideas were floated, civil-rights leaders were targeted, dissidents were cataloged, or entire data streams were taken without debate, people conclude the rules are optional for the powerful. That cynicism is its own national-security risk: it sours jury pools, depresses civic participation, and radicalizes fringes.

Not cartoon villains—structural incentives.

Many operators are earnest patriots. The problem isn’t that “everyone is bad”; it’s that secrecy + crisis + capability create predictable human incentives: to expand tools, to defend turf, to conceal failure, and to prefer the instrument already in hand. Without active, adversarial oversight and disciplined declassification, those incentives win—no matter who sits in the Oval Office.

Guardrails That Work (If We Use Them)

If we want the security state without a state-within-a-state, rules need teeth and clocks—and someone whose job is to bite when clocks run out. Here’s how the fixes you sketched translate into practice, with the lessons of the JFK–Church era and the post-9/11 sprawl in mind.

Church Committee 2.0 (recurring).

A standing, once-a-decade public inquiry into classified programs with subpoena power, immunity tools for whistleblowers, and a declassification budget. Scope rotates: foreign covert action one cycle, domestic collection authorities the next. Deliverables: a public report, a classified annex to the intel committees, and a required up-or-down vote on recommendations within 180 days. Sunlight is a policy tool—make it routine, not exceptional.

Declassify by default.

Flip the presumption: documents auto-declassify on a short fuse (e.g., 5 years) unless a specific, renewable harm test is met. Create an independent declassification referee (outside the agencies) that can overrule stamps; track agency “over-classify” rates and dock budgets for abuse. Information is power; hoarding it is politics.

Tighten surveillance law.

Raise FISA thresholds and close gray zones (e.g., no “about” collection via back doors). Put permanent, security-cleared adversarial advocates in the secret court to argue the privacy side. Require narrow orders, short durations, and automatic sunsets for all emergency powers—lapse unless re-justified with fresh evidence and narrower scope.

Program-level audit trails.

No more black-box top lines. Inspectors general and the intel committees need line-item visibility, standard cost codes, and clawback authority when programs violate charters. Mandate machine-readable logs (access, tasking, minimization actions) with immutable hashes so after-action reviews can’t be massaged.

Clear red lines, codified.

Write bright-line bans into statute: torture, non-consensual human experimentation, domestic political spying, bulk collection on U.S. persons. Close contractor end-runs by making primes legally indistinguishable from the agencies when performing inherently governmental functions, with personal liability for managers who circumvent controls. Require named, personal sign-offs for exceptional operations—with consequences (discipline, disbarment from clearances) when lines are crossed.

Narrow the mission.

Treat covert action as the last resort, not the first impulse. Before authorizing, require a signed comparison memo: overt law-enforcement and diplomatic alternatives, predicted second-order effects, exit criteria, and a blowback plan. Every covert action order should carry a sunset and an exit ramp; re-ups must show measured gains and updated risk.

Whistleblower lanes that actually work.

Protected, cleared pathways to IGs and the intel committees; expedited adjudication; retaliation penalties with teeth. Add a periodic, anonymized scoreboard of complaints and outcomes so Congress and the public can see if the channels are real or decorative.

Targeted secrecy, not blanket opacity.

Use compartmented briefings instead of outright stonewalling: more members and staff see the what and why, while the how stays narrow. Pair that with after-action public summaries once operations close—enough facts to sustain democratic consent without burning sources and methods.

Public metrics.

Publish aggregate stats (with a lag): number of FISA orders sought/granted/modified, instances of minimization, programs retired vs. extended, declassification rates by agency, IG findings closed vs. open. What gets measured gets managed; what stays hidden metastasizes.

Emergency powers on a leash.

Any “temporary” authority (pandemics, terror spikes, cyber crises) should self-destruct unless Congress renews it after open hearings that include civil-liberties and technical experts. Require post-mortems: what worked, what didn’t, what should never be used again.

Civic redundancy.

Fund independent archivists, FOIA litigators, and investigative journalism fellowships focused on national security. Healthy ecosystems need external predators; accountability shouldn’t depend only on insiders doing the right thing.

Bottom line: structure beats intentions. Build in clocks, counters, and consequences, and the inevitable crises won’t quietly re-create the very shadow system oversight was meant to tame.

A Better North Star

“Deep state” is a chant, not a plan. The adult task is simpler and harder: keep the tools we genuinely need—and keep them leash-trained. That means Congress doing its job especially when fear is loudest; courts insisting on warrants and narrow orders; inspectors general with budget and bite; and citizens refusing to live under a permanent emergency.

We built a wartime machine for existential fights. It worked—and then it kept working when the wars ended. The OSS became the CIA; Cold War habits ossified; Hoover and Angleton showed how secrecy breeds leverage; and presidents learned there were rooms in Washington where unelected people could say “no.” The Church Committee proved a republic can bottle the genie: sunlight, bright-line bans, and real oversight pulled the system back inside the law.

After 9/11 we uncorked it again. Patriot-era authorities sprawled; black sites and bulk collection returned; budgets ballooned behind classification walls. Snowden’s leaks didn’t just reveal programs; they revealed how easily temporary becomes default when no clock is attached.

So the choice isn’t “safety or liberty.” It’s safety under law—or safety on loan from a power that answers to itself. The north star is constitutional:

- Necessity, proportionality, and time limits on secret powers.

- Specific, reviewable justifications instead of blanket opacity.

- Personal accountability for crossing red lines (torture, domestic political spying, end-runs through contractors).

- Routine sunlight (recurring Church-style inquiries, aggressive declassification) so public consent stays informed, not presumed.

Most people in the system are earnest patriots; the failure is structural. Fix the structure—add clocks, counters, and consequences—and crises won’t quietly rebuild a shadow government. Keep the tools. Shorten the leash. And make the leash visible enough that the public can see it’s still there.

We needed a wartime intelligence machine. We built one. We learned—painfully—what it does when left unchecked. Church showed that a republic can bottle the genie. After 9/11, we let the monster grow again.

The choice now isn’t between safety and liberty. It’s whether we’ll demand safety under law—or settle for safety on loan from a power that answers to itself.

Mortimer Adler’s Four Levels of Reading and apply it directly to your article “Genie, Bottle, Monster.”

Mortimer Adler’s Four Levels of Reading and apply it directly to “Genie, Bottle, Monster.”

1. Elementary Reading

This is just recognizing words and grasping the most surface meaning.

- At this level, someone could understand that the article is about “the CIA,” “9/11,” and “a monster let out of the bottle.”

- But they would miss context—why Truman’s regret mattered, what the Church Committee exposed, or how Israel fits into the narrative.

- Not sufficient.

2. Inspectional Reading (Skimming & Superficial Reading)

Here you can scan quickly for the big picture.

- A reader would see the three phases: genie escaped → bottle reforms → monster unleashed.

- They’d notice Truman’s regret, the Church Committee, and 9/11 as the pivot points.

- Enough to explain the basic storyline to someone else, but without deep understanding of historical connections or present implications.

- Good for an overview, but still shallow.

3. Analytical Reading (Deep Understanding)

This is where Genie, Bottle, Monster really sits.

- A reader must ask questions of the text: What was Truman warning about? Why was the Church Committee necessary? How did 9/11 alter the trajectory?

- They’d connect Truman → Church Committee → Bush/Patriot Act → “business as usual nexus with Israel.”

- Requires knowledge of history (JFK, Cold War, intelligence community, Middle East wars) and willingness to follow cause-and-effect.

- This is the minimum level needed to fully read and watch this material.

4. Syntopical Reading (Comparative / Across Texts)

Here you compare multiple sources, weigh contradictions, and fit the article into a bigger tapestry.

- Example: Reading Truman’s 1963 op-ed, the Church Committee reports, Bush-era speeches, 9/11 Commission Report, and critiques like The Naked Capitalist.

- You don’t just absorb the article—you test it against other accounts, ask what overlaps, what diverges, and why.

- This is how you get beyond rhetoric to see patterns across decades.

- This is the level if you want mastery, not just comprehension.

The Genie and the Monster: How U.S. Intelligence Grew Into a State-Within-a-State—Bottled by Church, Unleashed After 9/11

Below is a crisp, point-by-point walk-through of Johnny Harris’s “Deep State” (CIA as wartime tool → “cancer,” bottled by Church → unleashed again after 9/11).

1) What are we even talking about?

- The term “deep state” is politically loaded (often a catch-all for “stuff I don’t like”). Harris tries to treat it earnestly: a durable, unelected power network inside the national-security state that can outlast presidents and sometimes go rogue.

2) Cuban Missile Crisis as x-ray of real power

- During the 1962 crisis, JFK leaves the West Wing for a Georgetown cocktail party—because that is where the men he trusts (and who truly wield power) live and trade notes.

- Named neighbors: Allen Dulles, Frank Wisner, William Colby, Chip Bohlen, Felix Frankfurter—senior spymasters/diplomats/jurists.

- Takeaway: alongside constitutional government sits an unelected, secretive power center with outsized sway.

3) Origins: From OSS to CIA

- Pre-WWII, U.S. intel geared up only in wartime, then stood down.

- Pearl Harbor gives FDR license to build the OSS under “Wild Bill” Donovan—a Wall Street lawyer who loves covert ops.

- OSS does anything that works: sabotage, propaganda, front companies, psychological ops—even harebrained schemes.

- After victory, Truman dissolves the OSS (fear of an “American Gestapo”).

- Early Cold War fear of the USSR flips Truman; the National Security Act (1947) creates the CIA with a vague mandate (“other functions and duties” related to national security). Everyone understands that means covert action—just not written down.

4) The CIA’s postwar “crime spree” (Harris/Morley framing)

A rapid-fire list of marquee operations:

- Paperclip (recruit Nazi scientists).

- Italy 1948 election interference.

- Iran 1953 (Ajax) coup.

- Guatemala 1954 coup (United Fruit interests loom).

- Congo, Indonesia, Greece interventions.

- Chile 1970–73 (including plotting around Gen. Schneider; Allende’s overthrow).

- Bay of Pigs.

- MKUltra (non-consensual LSD/mind-control research).

- Operation SHAMROCK (warrantless signals collection).

- Phoenix Program in Vietnam (tens of thousands killed, per Colby).

- COINTELPRO/CHAOS/Mockingbird (domestic targeting; media penetration).

- Thread running through: corporate influence, plausible deniability, and secrecy.

5) Secrecy as leverage (and blackmail)

- J. Edgar Hoover (FBI) and CIA counterintelligence chief James Angleton amassed kompromat; could quote bedroom conversations back to targets.

- Congress often didn’t want to know; CIA budgets were waved through with minimal line-of-sight.

- Truman later writes that the CIA “should be abolished.”

6) Vietnam → domestic spying → public backlash

- Operation CHAOS spies on the anti-war movement; reports repeatedly say it’s not foreign-controlled—yet the spying expands.

- Growing shock at domestic surveillance of citizens.

7) The Church Committee (1975–76): bottling the genie

- Sen. Frank Church drags secrets into daylight: assassination ideas (poison dart gun), MKUltra, COINTELPRO, illegal NSA taps, media infiltration, targeting MLK and activists.

- Finds executive secrecy + congressional indifference created a shadow system.

- Reforms follow: standing oversight committees, reporting requirements, some guardrails.

- Agencies smear Church, but reforms mostly stick for a time. Democracy works (imperfectly), Harris argues.

8) 9/11: the monster is unleashed again

- Patriot Act, new departments/programs, a mega-expansion of classified projects and buildings.

- CIA/NSA revive and vastly scale practices: torture, warrantless wiretapping, bulk surveillance.

- Snowden exposes the architecture; presidents who promise to “rein it in” often can’t.

- Core trade: we’re swapping freedom for security—and rebuilding a semi-autonomous security branch outside the founders’ checks.

9) Harris’s bottom line

- Secrets can save lives—but they also corrode accountability.

- Information is power; overclassification concentrates it.

- The only antidote is sustained oversight that resists crisis-era “anything goes.”

Does your thesis fit the episode?

“The CIA began as a wartime necessity and became a cancer; Church bottled the genie; 9/11 unleashed the monster again.”

That’s very close to Harris’s arc:

- Cancer: He catalogs a two-decade “crime spree,” blackmail leverage, and corporate entanglements—pathologies of unaccountable power.

- Bottled: Church-era sunlight + structural oversight partially contained it.

- Unleashed: Post-9/11 urgency re-supercharged the apparatus beyond what 1970s guardrails could restrain.

He does add nuance: many operators believed they were patriots in an existential struggle; the real failure was structure + secrecy, not simply “bad people.”

What a stronger title looks like (your emphasis)

Pick one of these (all reflect your “genie/monster” framing while staying factual):

- “Genie, Bottle, Monster: How U.S. Intelligence Escaped, Was Reined In, and Broke Loose After 9/11”

- “From Wartime Tool to Runaway Power: Church Bottled It—9/11 Unleashed It”

- “The Deep State, Then and Now: Bottled by Church, Unleashed by 9/11”

- “An American Gestapo? How the CIA’s Power Was Contained—and Reborn After 9/11”

If you want the takeaways turned into reforms (quick hit list)

- Church Committee 2.0: periodic, public-facing oversight inquiries.

- Declassify by default: strict clocks, penalties for over-classification.

- Tighten FISA & bulk collection: raise warrants, sunset authorities.

- Budget sunlight: stop black-box top-line approvals; require program-level audit trails.

- Clear red lines: codify bans on torture, domestic political spying, and contractor end-runs.

- Rein in corporate capture: bar conflicted boards/clients from policy leverage.