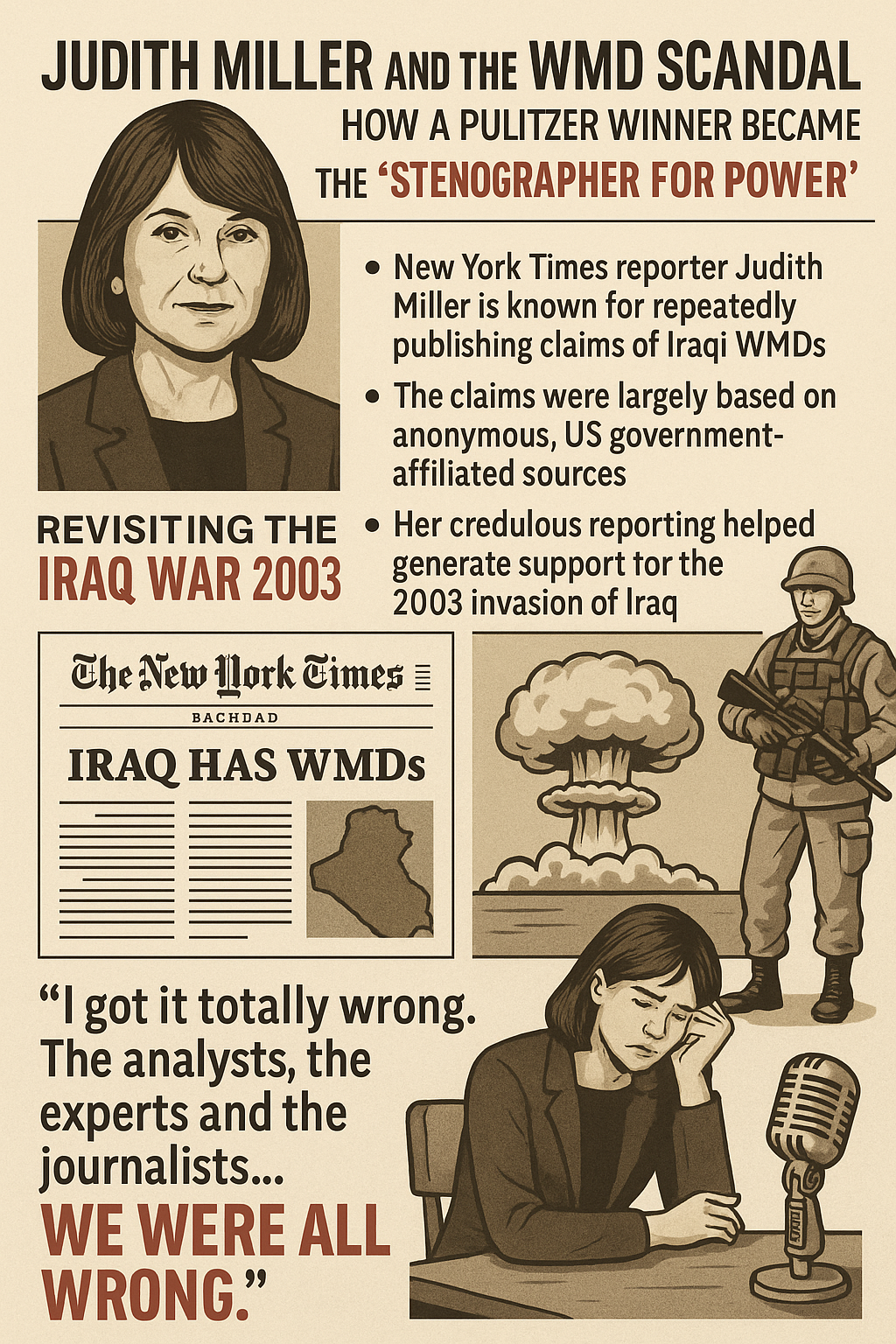

When history recalls the lead-up to the Iraq War, one journalist’s name appears again and again: Judith Miller. Once a Pulitzer Prize–winning reporter at The New York Times, she became infamous for her reporting on Saddam Hussein’s alleged weapons of mass destruction. Her articles, built on shaky sources and fed by a White House eager to sell a war, helped shape public opinion in favor of the 2003 invasion.

The story of Judith Miller is not simply about one reporter. It is a cautionary tale about journalism, government manipulation, and the catastrophic costs of unquestioned narratives.

A Star Reporter With Rare Access

Miller had built her reputation covering the Middle East. By the late 1990s, she was a veteran reporter, trusted by editors, and well-connected in intelligence and political circles. After 9/11, her prominence grew. She had access to officials in the Bush administration and defectors from the Iraqi opposition, particularly members of Ahmad Chalabi’s Iraqi National Congress (INC).

For the administration, Miller was the perfect conduit: respected, high-profile, and backed by the prestige of The New York Times.

The Aluminum Tubes and the Smoking Gun

On September 8, 2002, Miller co-authored one of the most consequential articles of the era:

“U.S. Says Hussein Intensifies Quest for A-Bomb Parts” (The New York Times).

The piece reported that Iraq had sought to acquire thousands of aluminum tubes “intended as components of centrifuges to enrich uranium.” Officials implied this was evidence of Saddam’s renewed nuclear ambitions.

The article was splashed across the Sunday edition of The Times — and hours later, Vice President Dick Cheney appeared on Meet the Press, citing Miller’s story as proof of the nuclear threat. The echo chamber was complete: leaked information was laundered through the press and fed back to the public as independent verification.

The Sources: Defectors and Shadow Intelligence

Miller’s reporting leaned heavily on anonymous administration officials and exiles tied to Chalabi’s INC. Many of these defectors had a clear agenda: to convince Washington to topple Saddam Hussein and install them in power.

Meanwhile, within the Pentagon, the Office of Special Plans (run by Donald Rumsfeld and Paul Wolfowitz) was cherry-picking intelligence to support a war already decided upon. Miller became one of the main vessels for this “alternative” intelligence.

The Knight Ridder Contrast

While Miller’s stories dominated front pages, reporters at Knight Ridder (Warren Strobel, Jonathan Landay, and John Walcott) were filing articles that questioned the entire case for war.

Their sources within the CIA and State Department warned:

- The aluminum tubes were unsuitable for centrifuges.

- Saddam had no operational ties to al Qaeda.

- Evidence of WMD stockpiles was circumstantial at best.

The difference was stark. Where Knight Ridder asked, “Is it true?”, Miller too often asked, “Who can confirm this narrative?”

The Fallout and The Times’ Apology

As the occupation dragged on and no WMD were found, Miller’s reporting came under intense scrutiny. In 2004, The New York Times issued a rare editorial apology to its readers, acknowledging that its Iraq coverage — much of it Miller’s — was flawed and overly reliant on dubious sources.

Miller left the paper in 2005, her reputation tarnished. In later interviews and in her memoir The Story (2015), she defended herself, arguing that she reported what her sources told her and that intelligence failures were systemic, not personal. But critics argue she blurred the line between investigator and advocate, becoming, in effect, a megaphone for the Bush/Cheney administration’s case for war.

Lessons From the Miller Affair

- Access is not accountability. High-level sources can be the most unreliable when their political agenda is at stake.

- Anonymous sourcing corrodes trust. Without transparency, journalism risks becoming uncheckable propaganda.

- Groupthink is deadly. When most major outlets echoed the same talking points, dissenting voices (like Knight Ridder) were marginalized.

- The cost of failure is not abstract. The Iraq War claimed the lives of over 36,000 American troops (killed or wounded) and more than a million Iraqis, destabilizing an entire region — all on the basis of false claims that journalists helped amplify.

The Legacy

Judith Miller’s story is not just about one reporter’s fall from grace. It illustrates how journalism can be weaponized when it prioritizes access and spectacle over skepticism and truth.

In Shock and Awe, the film about Knight Ridder’s lonely stand, her role is portrayed as emblematic of the mainstream press’s failure. While Miller insists she was a scapegoat for broader intelligence failures, her reporting remains a case study in how journalism can either hold power to account — or become its most effective tool.

As John Walcott put it to his reporters:

“When the government says something, you only have one question to ask: Is it true?”